What's behind the deadly strep A outbreak in the U.K.?

The cluster of cases has led to a run on home tests and fears of low antibiotic supplies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

So far this year, 15 children have died tragically of strep A infections in the United Kingdom. The outbreak has led to a run on home strep tests and strained supplies of antibiotics as parents fear for their children's safety. How unusual is the outbreak, what are leading infectious disease experts saying about it, and what can people do to protect themselves and their families? Here's everything you need to know:

What is strep A?

Most people think of strep throat as an irritant, a slightly more complicated cold that must be treated with antibiotics. But one type of the pathogen, group A streptococcus or "strep A," is a true scourge that kills about 500,000 people per year globally — 150,000 directly and 300,000 from rheumatic heart disease, a disease that can emerge years later after untreated childhood strep A infections. The disease is most deadly in low or middle-income countries and there is currently no vaccine. Most people will experience mild symptoms with strep A, and treatment with penicillin is sufficient to ward off tragic outcomes, but some who can't fight off the infection suffer from Scarlet Fever or from a syndrome called invasive Group A streptococcus (iGAS), which can cause organ failure and toxic shock syndrome.

There have also been mysterious and deadly cluster outbreaks in the past. In 1998, for example, 26 people, including nine children, died of strep A in Texas. According to the CDC, strep A kills between 1,100 and 1,500 Americans a year. Four children under 10 years old died in the U.K. in the equivalent period in 2017-2018, according to CNN, and 27 overall during that season. But this year's toll is already dramatically higher. What's actually going on? U.K. health authorities maintain that there is no new strain of strep A circulating, nor is there any observed decrease in antibiotic effectiveness.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Theories abound. Some speculate that the difficulty in obtaining appointments with general practitioners in the U.K. may be contributing to lags in treatment that turn deadly. Pharmacists in the country have complained about interruptions in the supply of antibiotics. It certainly could be that a healthcare system under strain from COVID, flu, RSV, and now strep A is partly to blame, along with less masking and a general increase in socializing and indoor activity. But the liveliest debates involve COVID.

What does COVID have to do with the strep A outbreak?

The most common explanation, not just for the strep A outbreak but also for the resurgence of various viral respiratory diseases in children this year, is the idea of immunity debt. At the population level, fewer exposures to the flu, RSV, and other viruses and pathogens in the previous two years, especially for children born during the pandemic, means that there are many more people susceptible to infection than in a "normal year." As Johns Hopkins University physician Michael Rose put it in a recent article for Slate, children "whose immune systems haven't been properly primed are more prone to infection and severe disease." Most people will get some short-term immunity after a strep A infection and so there may be more children vulnerable to serious outcomes from this pathogen than there would have been in pre-pandemic seasons.

Some researchers, however, are convinced that the U.K.'s strep tragedy is indicative of a broader problem — that COVID has done temporary or even permanent damage to the immune systems of those who contracted and survived the virus. Perhaps the leading proponent of this theory is T. Ryan Gregory, a Canadian evolutionary biologist at the University of Guelph. As he put it in a series of Twitter threads that have been shared thousands of times by other users, "COVID infection (let alone repeated infections) may rob people of a working immune system, which puts them at risk for other infections." Gregory, who has not published scholarship on infectious disease, has used this basic framework to explain a variety of unexpected surges, including what looks to be a particularly bad flu season, the explosion of RSV cases in children, and now the U.K.'s strep A problem.

Gregory and other proponents of the immune dysregulation theory believe that it is obviously behind the U.K. strep A epidemic. But it is not clear why strep A would be causing this issue in the United Kingdom alone at this time, given that a significant percentage of the human population of the planet has been infected with COVID and streptococcus is endemic. Because countries with much lower reported case numbers than the United States or the U.K. have also experienced RSV surges, it seems unlikely that widespread COVID-triggered immune deficiency is a significant cause of any of the winter illness problems we are seeing.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What can we learn from the outbreak?

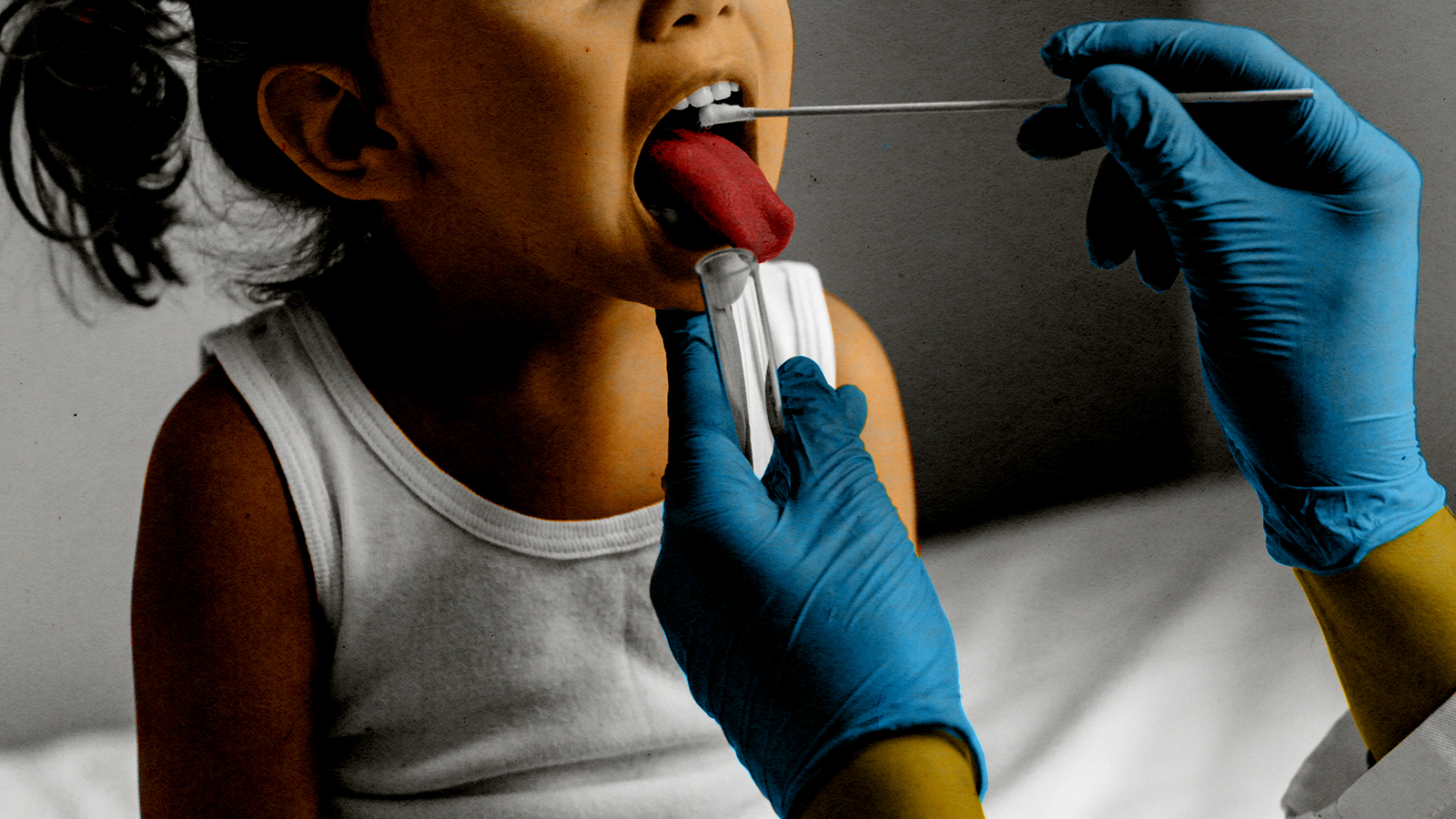

As with any medical controversy, we may never know with 100 percent certainty exactly what is causing the strep A problem in the U.K. If your child is sick, you probably don't have time to wade into complicated medical debates about the relationship between strep A and COVID. More important is to have your child (or yourself) seen by a doctor immediately if you see any of the following symptoms: "very red, very sore throat" accompanied by a fever of 101 or higher, a sandpapery rash, a whitish coating or bumps on the tongue, or swollen lymph nodes.

Rapid strep A tests are available over the counter, and worried parents might feel better if they have a few on hand (although please don't panic buy in bulk). Doctors should remain on alert for what seems like common cold symptoms in a young child that might be something potentially more lethal, and some health authorities are recommending a proactive approach of prescribing antibiotics even for unconfirmed cases of strep.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without people

Tips for surviving loneliness during the holiday season — with or without peoplethe week recommends Solitude is different from loneliness

-

More women are using more testosterone despite limited research

More women are using more testosterone despite limited researchThe explainer There is no FDA-approved testosterone product for women

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures

-

Food may contribute more to obesity than exercise

Food may contribute more to obesity than exerciseUnder the radar The devil's in the diet

-

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?Under the radar Catching diseases, not those ever-essential Zzs

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

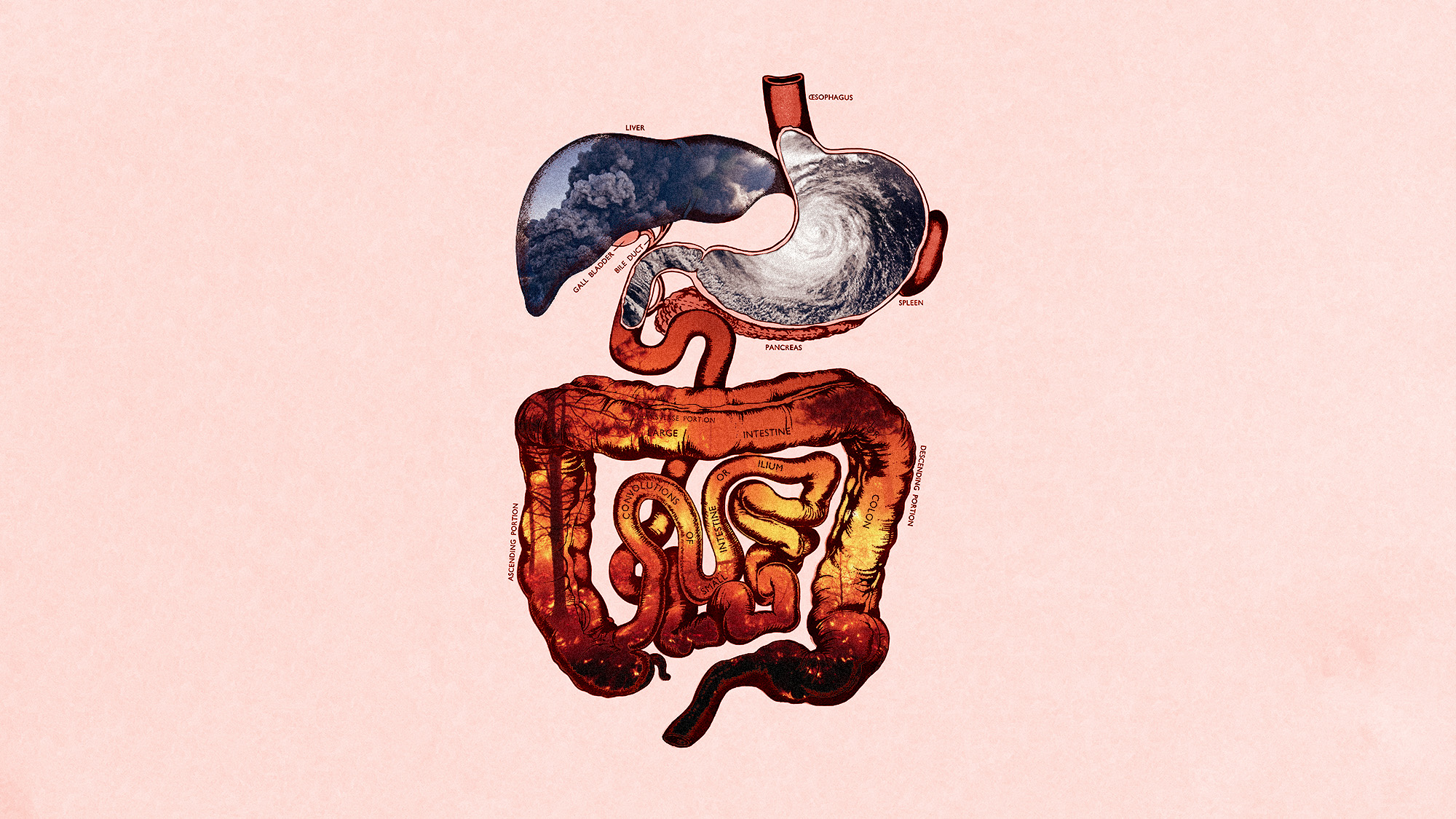

Climate change can impact our gut health

Climate change can impact our gut healthUnder the radar The gastrointestinal system is being gutted