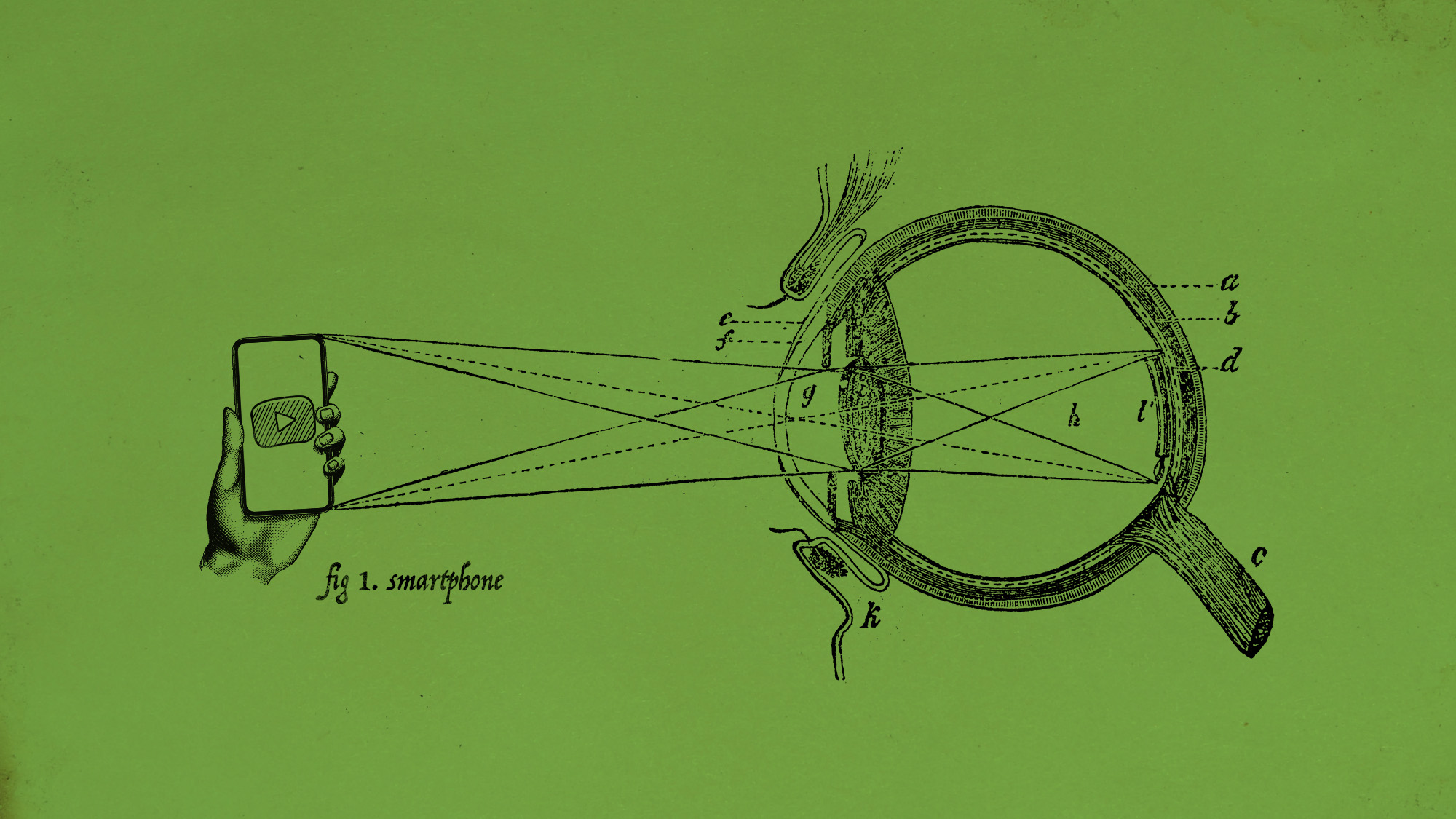

Excess screen time is making children only see what is in front of them

The future is looking blurry. And very nearsighted.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is time for kids to put down their phones. Children are becoming nearsighted younger and faster, mostly because of their time spent on screens. The problem is only expected to worsen as technology advances. While there are more permanent treatments for nearsightedness in the works, nearsighted children tend to require glasses or contacts for life, and more severe cases can lead to more extreme eye ailments down the line.

A fuzzy future

Myopia, also known as nearsightedness, "is an unusual elongated growth pattern of the eyeball, which usually begins in childhood and is likely caused by genetics and environment," as defined by Harvard Public Health. The condition makes objects in the distance appear blurry, making it difficult to see far away. Myopia can lead to more severe eye problems in the future including, "glaucoma, cataracts, retinal tears, and macular degeneration — all diseases which can rob someone of their sight entirely." Experts predict that half of the global population will be nearsighted by 2050.

The problem is children are developing myopia earlier, likely because of increased screen time and a lack of sunlight exposure. "We're talking about [children who are] age 4 or 5 years old," Dr. Maria Liu, an associate professor of clinical optometry at The University of California, Berkeley, told NPR. Myopia rates increased significantly during the Covid-19 pandemic. Social distancing and the switch to remote learning during the pandemic augmented the amount of screen time children are exposed to both on smartphones and computers. "For a young child whose eyes are still developing, these habits cause their eyes to prioritize near vision rather than distance vision. In turn, their eyeballs begin to elongate, triggering nearsightedness," NPR explained. Screen time is not just a problem in young kids either. A 2019 study found that 84% of teenagers in the U.S. own a personal smartphone.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Bringing back focus

While genetics play a part in developing myopia, parents can take steps to reduce the risk of their children developing it, namely by controlling screen time and encouraging time spent outdoors. A 2021 study found that since the pandemic, children's average screen time was more than seven hours per day. In another study, the Pew Research Center found that 46% of teens reported using the internet "almost constantly."

Leaving myopia untreated, especially in children, can exacerbate the problem and increase the future risk of more severe problems. The typical way to treat myopia is by wearing glasses or contacts, and those usually have to be worn for life. Researchers are also studying specific treatments to permanently cure myopia. Special contact lenses, called orthokeratology, have helped slow the progression of nearsightedness in some children. The lenses are hard and have to be worn overnight, but according to NPR, they "can reshape the patient's eyeballs back to a healthy spherical shape while potentially correcting their vision," similar to "wearing a retainer for teeth."

While this treatment is not accessible to everyone, other measures can be taken. Exposure to sunlight and outdoor open spaces has been shown to help with myopia. NPR explained, "Our eyes can sense the walls and ceiling when we are indoors, which crowds our peripheral vision." Taking regular breaks from staring at a screen to spend time outside and scan the horizon can give eyes a much-needed break. "Kids are busy with structured activities and when they're given the opportunity to have free time, they often choose inside activities like electronics," Dr. Jennifer Haggar, a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, told The Wall Street Journal. The best thing to do is for parents to "try and get their kids outside — playing outside," Mark Rosenfield, professor at the State University of New York College of Optometry, told Harvard Public Health. "It's a win-win situation."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

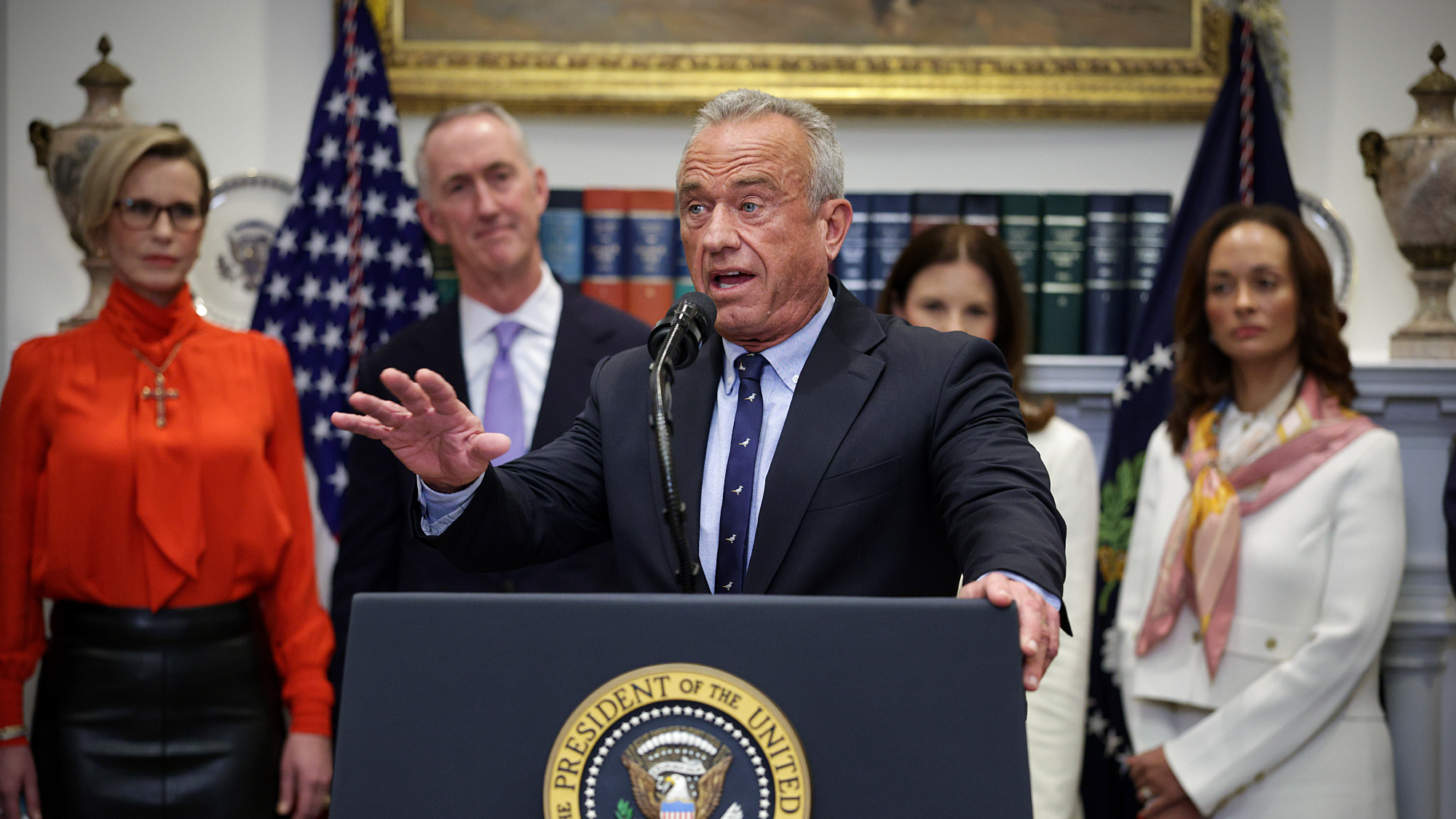

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

The expanding world of child skincare

The expanding world of child skincareUnder the Radar Beauty line for kids as young as three sparks ‘rage’