Biden is still acting like the 'senator from Obama'

A lifetime in the Senate didn't prepare him for the Oval Office

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Biden won the 2020 election by making two pledges: not to be Donald Trump, and to return something approaching regular order to Washington politics.

The 46th president checked the first box on Inauguration Day, but he has failed to tick the second for a curious reason: Despite a half-century of building expertise in the way Washington operates, Biden's legislative experience didn't prepare him to govern from the executive branch. He wasn't ready to make decisions and follow through to ensure his objectives were achieved.

Perhaps that shouldn't surprise us, because his résumé wasn't typical of modern presidents. Since World War II, U.S. political parties have tended to nominate presidential candidates with some executive-level experience, either in the public or private sector. (Former Presidents John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama are the two exceptions.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Granted, it's impossible to be fully prepared to become commander-in-chief. But the parties generally choose standard-bearers who have managed an enterprise, made decisions, and been held accountable for the consequences — better training for a chief executive than, say, raising money, making speeches, and voting.

Consider the pre-presidency résumés of the postwar presidents. Dwight Eisenhower led the Allies to victory in World War II. Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush were governors. Even Donald Trump was a businessman, or at least he played one on TV.

Like Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush, Biden was a two-term vice president. But Nixon had also been a logistics whiz as a Naval officer in World War II, running the Alameda Naval Air Station in California. He negotiated the termination of war contracts with Naval suppliers before his commission ended, receiving promotions along the way. Likewise, Bush 41 was U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, chaired the Republican National Committee, and headed the CIA.

Where the other two former veeps had ample administrative experience, Biden's primary background is in the legislature and on the campaign trail. Even as vice president, he essentially was a super-legislator, the White House's informal liaison to Congress — or, as Andrew Taylor, a political science professor at N.C. State University, told me, "the senator from Obama."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Biden's tenure stands in sharp contrast to that of former Vice President Al Gore, Taylor added. Gore received an actual policy portfolio from Clinton: He led the National Performance Review and the administration's technology policy; was the Clinton administration's point person in diplomacy with China; and had responsibilities similar to those of a Cabinet official.

Biden's vice presidency was centered on winning over lawmakers, mostly from Republican majorities. When Biden's second term as veep ended, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), then majority leader, paid tribute to his friend's legislative acumen. "We got results that would not have been possible without a negotiating partner like Joe Biden," he said. "Obviously, I don't always agree with him, but I do trust him, implicitly. He doesn't break his word, he doesn't waste time telling me why I'm wrong," McConnell continued. "There's a reason 'Get Joe on the phone' is shorthand for 'Time to get serious' in my office."

Now Democrats control Capitol Hill by slender margins. They'll run in the 2022 midterms on the Biden administration's accomplishments. The trouble is there aren't many, apart from the American Rescue Plan — which seems more like an extension of the measures passed in the final months of the Trump presidency than anything new, and which has been plagued with bureaucratic snafus. It's another signal Biden and his team aren't great managers.

Other policies executed on the president's watch haven't gone well. Most Americans supported withdrawing from Afghanistan but opposed Biden's botched exit plan.

The post-pandemic recovery is slowing, if not stalling. Gross Domestic Product grew at a 6.7 percent annualized rate in the second quarter of this year, but third quarter numbers, announced Thursday, showed the growth rate sputtering at 2 percent. Labor markets remain tight, as millions of workers affected by the pandemic simply refuse to return to the workforce, and consumers are feeling the bite of inflation that seems more persistent than transitory. The prospect of economic growth lagging inflation conjures images of the sort of stagnant economy we haven't seen in more than four decades.

The on-again, off-again status of a seemingly popular infrastructure plan has shaken Americans' confidence in the administration's competence, too. And whatever you think of Biden's Build Back Better agenda — as a fiscal conservative, I'm alarmed at the reckless spending — it's indisputable that he has stumbled spectacularly. The spending framework announced Thursday is dramatically smaller than the package the president originally proposed.

All these troubles are eroding Biden's public standing and, with it, the standing of his party. His approval numbers turned negative for the first time in late September, and Republicans increasingly seem likely to retake Congress in 2022.

Biden needs better administrative skills to avoid that fate, but he can't exactly take a sabbatical from the presidency to gain executive chops at a Fortune 500 company.

Still, he has options. He could replace Chief of Staff Ron Klain with someone who can impose more discipline and offer more political savvy, as Leon Panetta demonstrated when the Clinton administration was foundering in its first term. Panetta's successor, Erskine Bowles, likewise helped Clinton survive impeachment.

For Biden, a Democratic governor who's a former member of Congress — Jared Polis of Colorado? Michelle Luhan Grisham of New Mexico? — could bring executive and legislative experience to the White House. A Democratic CEO would offer an outsider's perspective along with management acumen, or a former White House chief of staff might make a needed comeback.

Rahm Emanuel ran a tight ship during the first year of the Obama administration. He's nominated to be ambassador to Japan, so clearly the president trusts him. Panetta and Bowles are still around, too.

Biden might need to get on the phone.

Rick Henderson is an award-winning writer and editor whose work has appeared in The New York Times, USA Today, the Los Angeles Times, Reason, The Dispatch, and many other publications. He and his family live in North Carolina. He's also the social director of the Raleigh Uke Jam.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

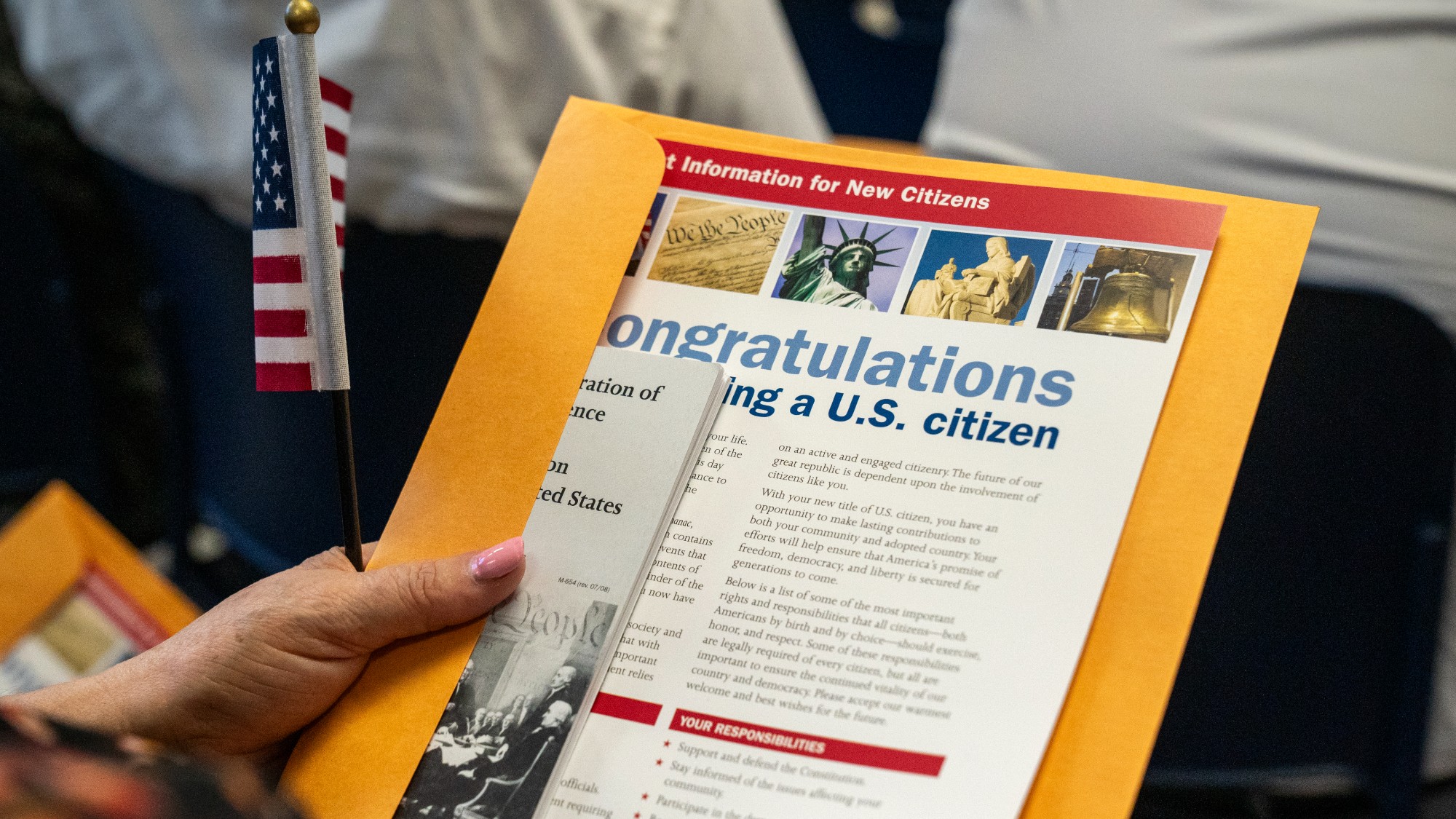

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugees

Memo signals Trump review of 233k refugeesSpeed Read The memo also ordered all green card applications for the refugees to be halted

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame game

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame gameFeature Kamala Harris’ new memoir reveals frustrations over Biden’s reelection bid and her time as vice president

-

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day