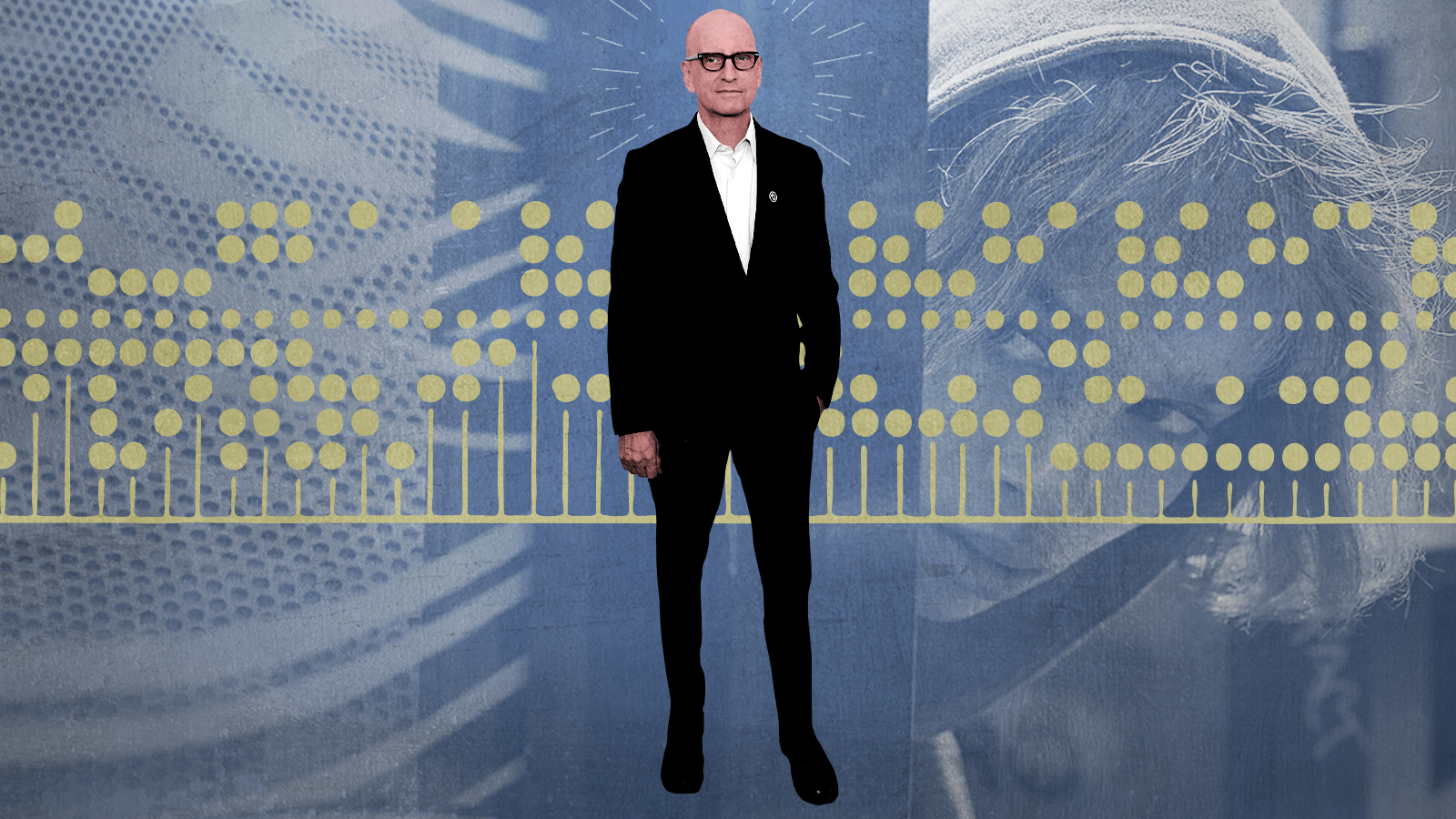

The obsession and salvation of technology in Steven Soderbergh's films reaches new heights in Kimi

'Kimi' isn't new territory for the director — and that may be the whole point

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first scene in Steven Soderbergh's latest film, Kimi, features an all-too-familiar sight: a man giving an interview over Zoom-like software — complete with a professional ring light set-up — while sitting in a closet partially decorated to look like an office, dressed professionally from the waist up.

Aside from being an accurate depiction of work-from-home life under COVID, it's also a neon-lit indicator of Kimi's tech-heavy milieu. For those familiar with Soderbergh's recent work, that theme will come as no particular surprise; far from a Luddite, the director's intrigue with the latest gadgets and technologies has not only allowed him to have more obsessive personal control over every aspect of his films — it may be the whole point.

Kimi follows Angela Childs (Zoë Kravitz), who works from home for a company that produces a Siri-like voice assistant called KIMI. Angela suffers from acute anxiety and agoraphobia following an assault, and thus never leaves her lavish Seattle apartment, which is technologically optimized for perpetual isolation. Her professional and personal life is mediated by screens and voice-controlled tech. In an obvious signpost of her quarantined interiority, she frequently shuts out the world using noise-canceling headphones, which Soderbergh conveys by muting the urban cacophony that otherwise dominates the film's sound design.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

However, Angela's isolation is not built to last. While reviewing various audio files to better optimize KIMI's voice-command responses, she overhears a rape and murder that, unbeknownst to her, goes straight to the top of the corporate ladder. After being forced to finally leave her home to report the issue, she's confronted with a conspiracy to snuff her out. With Kimi, Soderbergh effectively remixes the paranoid thriller for the age of surveillance capitalism. His cinematic nods to Rear Window, The Conversation, and Panic Room — to name a few — are no less successful for being overt. It's taken as a given that Angela is being watched through the tech she willfully uses. Her concern, as well as Soderbergh's, is who's doing the watching and why.

Kimi's technological environment mirrors its director's interest in the same tools. An early digital adopter, Soderbergh has embraced low-cost technology ever since the prototype for the RED One digital camera was made available to him ahead of filming for his two-part epic Che (2008). Indeed, ever since he attempted to bypass traditional studio-backed theatrical distribution for his heist comedy Logan Lucky (2017), Soderbergh's films have almost exclusively featured small crews and speedy productions despite often employing large acting ensembles. He's known for editing footage the same day it was shot, often in transit from the set, as well as quickly jumping into new productions as soon as the previous one has wrapped.

That's not to say these filmmaking methods have rendered Soderbergh's work aesthetically stagnant. He experimented with down-scaling his visual style with Unsane (2018) and High Flying Bird (2019), both of which were shot on low-mass iPhones. His previous film, the period crime caper No Sudden Move (2021), employed a wide-angle lens that curved the frame, albeit to an oft-distracting degree. Kimi is also the fifth Soderbergh feature to be primarily released via a streaming service; his last three films for HBO Max (Let Them All Talk, No Sudden Move, and Kimi) weren't given even a limited theatrical run.

This isn't new territory for Soderbergh, whose interest in alternative distribution strategies dates back to his film Bubble (2006), which was released in theaters the same day it was broadcast on HDTV. It's unclear if he has any interest in releasing his future work theatrically, which is at least notable given that his debut feature — Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989) — revolutionized independent cinema a generation prior.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Soderbergh's emphasis on control and efficiency in production has bled onscreen in his most recent work. Every film from Unsane onwards has felt fleet and small scale relative to the features he released prior to his brief hiatus from filmmaking in 2013, even as his casts have frequently remained Ocean's sized. That isn't a commentary on quality; rather, Soderbergh's recent output has been mostly as entertaining and politically engaged as ever. His rotating group of screenwriters (Tarell Alvin McCraney, Scott Z. Burns, Deborah Eisenberg, Ed Solomon, etc.) has ensured that each film feels narratively different despite treading similar thematic territory, mainly capitalism and institutional malfeasance.

Kimi folds both of those ideas into a productively ambivalent technological critique. In the film, the KIMI device is a (morally, ideologically) neutral tool; it simply responds to the queries and commands asked of it. Yet the people behind KIMI are far from impartial observers. When Angela attempts to expose the crime she overhears, her immediate supervisor (Andy Daly) urges her to ignore it. When she kicks it up the ladder, her tech contact (Rita Wilson) praises her bravery and compassion in one breath and then turns her over to hired goons in the next. This is all to keep the crimes of KIMI's mild-mannered CEO (Derek DelGaudio) out of the press? before the company goes public. They not only confirm Angela's paranoia but also use her own device against her, tracking her phone through downtown Seattle in order to abduct her in broad daylight.

At the same time, KIMI plays a large role in saving Angela's life when she's finally cornered, responding to commands that effectively subdue her attackers. Angela initially uses technology to keep her plugged into the world even as she remained physically separate from it. Eventually, she uses it to stay alive long enough so that she can return to the world she abandoned. "Technology doesn't know that it's technology; it's agnostic," Soderbergh recently said in an interview with The Daily Beast. "It's how we employ it, and what sort of role we give it, that matters."

This view reflects how Soderbergh employs technology for filmmaking. For someone who has directed, photographed, and edited all of his films for the past decade, digital cameras and streaming services are merely a means to an end, tools that allow for maximum freedom and speed of production/release. They are mechanisms for him to continue crafting mass entertainment that sheds light on the governmental and corporate toxicity that permeates our daily lives.

It's telling, though, that Soderbergh hasn't turned his back on working with actors, something he's excelled at for his entire professional career. In Kimi, it's not just providing Zoë Kravitz with a showcase, but demonstrating how people can intervene when technology fails us. It's a group of protestors who save Angela after she's initially captured near a rally, and it's a curious neighbor who rushes to her aid after she's been drugged and kidnapped.

Soderbergh has always emphasized the ways in which interpersonal connection reigns supreme over any other mediating influence. Tools can only help us, but it's up to us to actually save each other.

Vikram Murthi is a freelance film/TV critic. He has contributed to The A.V. Club, The Nation, Filmmaker Magazine, Reverse Shot, and Vulture among other publications. He lives in Brooklyn but was born in Chicago. Follow him on Twitter.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 8 best superhero movies of all time

The 8 best superhero movies of all timethe week recommends A genre that now dominates studio filmmaking once struggled to get anyone to take it seriously

-

Heated Rivalry, Bridgerton and why sex still sells on TV

Heated Rivalry, Bridgerton and why sex still sells on TVTalking Point Gen Z – often stereotyped as prudish and puritanical – are attracted to authenticity

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

February’s new movies include rehab facilities, 1990s Iraq and maybe an apocalypse

February’s new movies include rehab facilities, 1990s Iraq and maybe an apocalypsethe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

The 8 best animated family movies of all time

The 8 best animated family movies of all timethe week recomends The best kids’ movies can make anything from the apocalypse to alien invasions seem like good, wholesome fun