What are ‘forever chemicals’ and how are they harmful?

The widely used pollutants have been linked to thyroid disease and cancers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pollutants known as “forever chemicals”, which build up in the body, may be toxic and do not break down in the environment, have been found at significant levels at thousands of sites across the UK and Europe.

A major mapping project found that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – a group of thousands of chemicals valued for their detergent properties – have made their way into water, soils and sediments.

The implications of the findings could be “staggering”, said NBC News. Here is what we know.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What actually are they?

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. It is an umbrella term for a family of thousands of chemicals – “about 12,000 at the last count”, said The Guardian – that are so robust they won’t break down in the environment for tens of thousands of years, hence the nickname “forever chemicals”.

They are used in many “everyday products” including non-stick pans, food packaging, carpets and furniture, said Sky News. Therefore, said The Guardian, “you may not realise it but you have an intimate relationship with PFAS” because the human-made chemicals are “in your blood, your clothes, your cosmetics”.

Can they harm humans and if so how?

They certainly can. A US study that ran between 2005 and 2013, involving the collection of blood samples from about 69,000 people living near a plant in West Virginia that emitted the chemicals, found that there was a “probable link” between exposure to them and six diseases: high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular cancer, kidney cancer and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

We can come into contact with PFAS compounds by drinking contaminated water or eating food grown or caught near to where the chemicals are produced. Foods commonly linked are fish, eggs, or milk, or livestock that has fed on contaminated land.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But to “fall foul of the worst effects”, said The Guardian, you would need to be exposed for a “sustained period of time to pretty high concentrations of the substances”, so most PFAS “health scandals” in the US and Europe have been related to contaminated drinking water supplies.

What about wildlife?

Drawing on more than 100 recent peer-reviewed studies of PFAS contamination in animals, the US-based Environmental Working Group found more than 120 unique PFAS compounds in animals, including some endangered or threatened species.

“We were like, ‘holy smokes, this is shocking,’” David Andrews, a senior scientist who worked on the review, told The New York Times.

The affected animals included large mammals such as polar bears, tigers, monkey, pandas, reptiles, birds, small animals such as cats, frogs, and many types of fish. Voles have also been linked.

When researchers at Cardiff University examined the livers of otters across England and Wales they found PFAS in all 50 otters sampled, with 12 types of PFAS found in 80% of the animals.

Forever chemicals have been detected in killer whales near Norway and in bottlenose dolphins stranded along the northern Adriatic coast.

What is being done to tackle the problem?

A Defra spokesperson said the UK had “very high standards” for drinking water and that water companies were “required to carry out regular risk assessments and sampling for PFAS to ensure the drinking water supply remains safe”.

Another government spokesperson said ministers are “working with partners to improve our understanding of the exposure of wildlife to chemical contaminants, including PFAS” by “analysing archived samples to address data gaps and get a picture across all environmental compartments, including soil, river, lakes and groundwater”.

“We are undertaking investigations to understand and map out the sources of PFAS, using additional controls to reduce their risk to the environment,” they added.

However, said Science Alert, “phasing out forever chemicals is a slow process so far”, and while US manufacturers have already eliminated some PFAS, many of the thousands of varieties are still in use.

Methods for disposing of PFASs “typically rely on expensive and harsh treatments, some of which require high pressures and temperatures above 1,000C”, said the science journal Nature.

But a new approach revealed by researchers last year showed a way to break down long-lasting chemicals that scientists say is easier and cheaper than the harsh methods currently used. Brittany Trang, an environmental chemist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, who co-led the latest study, told Nature: “There’s a need for a method to get rid of PFASs in a way that does not continue to pollute.”

Trang and her team showed “promise in breaking down one of the largest groups of PFASs using inexpensive reagents and temperatures of about 100°C”, said the journal.

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

‘Like a gas chamber’: the air pollution throttling Delhi

‘Like a gas chamber’: the air pollution throttling DelhiUnder The Radar Indian capital has tried cloud seeding to address the crisis, which has seen schools closed and outdoor events suspended

-

Eel-egal trade: the world’s most lucrative wildlife crime?

Eel-egal trade: the world’s most lucrative wildlife crime?Under the Radar Trafficking of juvenile ‘glass’ eels from Europe to Asia generates up to €3bn a year but the species is on the brink of extinction

-

What do heatwaves mean for Scandinavia?

What do heatwaves mean for Scandinavia?Under the Radar A record-breaking run of sweltering days and tropical nights is changing the way people – and animals – live in typically cool Nordic countries

-

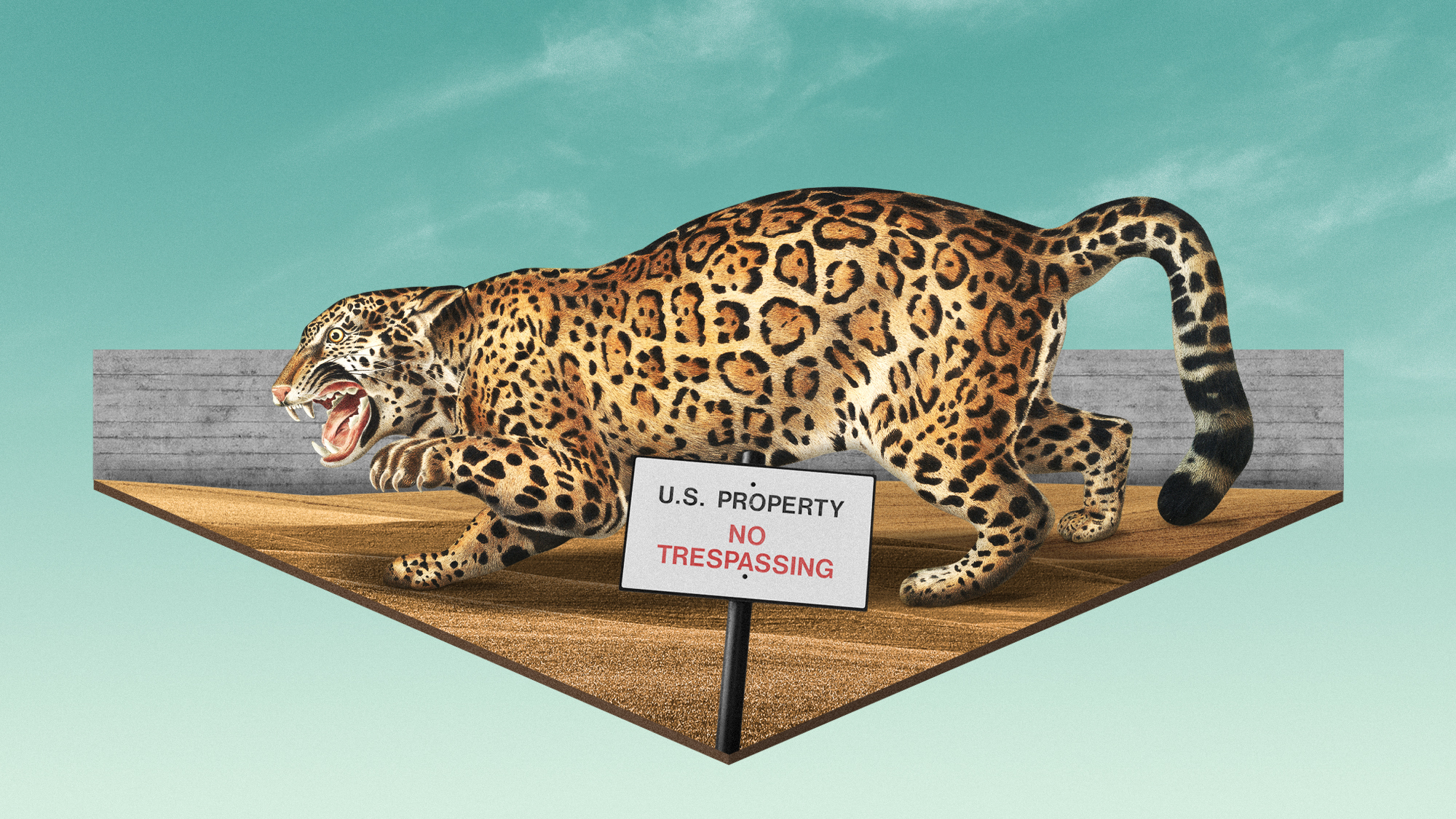

The revived plan for Trump's border wall could cause problems for wildlife

The revived plan for Trump's border wall could cause problems for wildlifeThe Explainer The proposed section of wall would be in a remote stretch of Arizona

-

Why is the world so divided over plastics?

Why is the world so divided over plastics?Today's Big Question UN negotiations on first global plastic treaty are at stake, as fossil fuel companies, petrostates and plastic industry work to resist a legal cap on production

-

Spiking whale deaths in San Francisco have marine biologists worried

Spiking whale deaths in San Francisco have marine biologists worriedIn the Spotlight Whale deaths in the city's bay are at their highest levels in 25 years

-

Anti-anxiety drug has a not-too-surprising effect on fish

Anti-anxiety drug has a not-too-surprising effect on fishUnder the radar The fish act bolder and take more risks