Kim Philby: unmasking the original Cold War double agent

New files reveal infamous Soviet spy could have been outed years before defecting

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kim Philby, Britain’s most infamous spy, could have been unmasked as a double agent years before he fled to the Soviet Union, newly declassified records have revealed.

According to files from the National Archive, which have been kept secret for 60 years, Philby confided to the British-Russian social campaigner Flora Solomon in 1938 that he was “100% on the Soviet side”. Philby, who eventually defected to Moscow in 1963, added: “I am helping them… I am carrying out a terrifically important and difficult assignment.”

Despite this revelation Solomon did not report her suspicions until 1962, when she told Victor Rothschild, a former MI5 officer, at a cocktail party in Tel Aviv.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“Her motivations for keeping Philby’s secret for 25 years, then eventually shopping him to the security services, remain mysterious,” said The Telegraph.

Who was Kim Philby?

Born in India in 1912, Harold “Kim” Philby was a pillar of the British establishment, attending Westminster School and then Cambridge University.

Having been “drawn towards communism at Cambridge”, he was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1934 with the aim, he would later claim, of overthrowing Western imperialism. Having worked as a journalist for The Times, he eventually joined MI6 and quickly rose through the ranks of the British intelligence service.

While working in Washington DC as MI6’s liaison with the CIA and FBI in 1951, two fellow Cambridge spies, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, fled to Moscow, turning the spotlight on to Philby.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

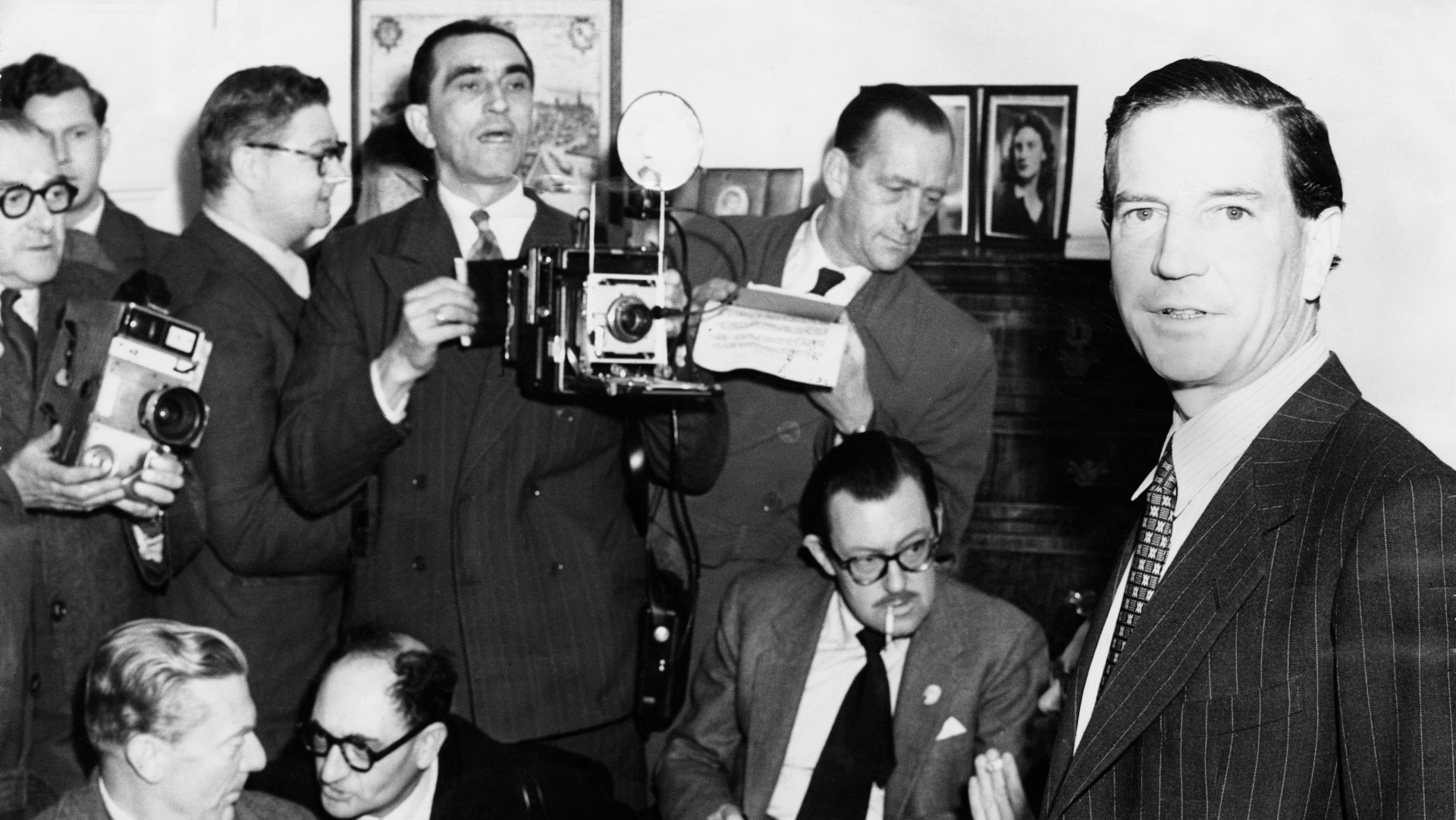

He was interrogated and eventually cleared but in 1955 was publicly accused of being the so-called “Third Man” in the spy ring. In an extraordinary press conference held in his mother’s flat in London, he managed to successfully convince journalists he was innocent.

Despite officially leaving MI6, he resumed life as a double agent while working as a newspaper journalist in Beirut, until he was finally unmasked in 1963.

The reason he got away with his double life for so long was twofold, said the BBC. “The first was the British class system, which could not accept one of their own was a traitor.” And the second “was the fact that so many in MI6 had so much to lose if he was proven to be a spy”.

Sky History said his ability to escape detection for so long was more down to “a mixture of luck and shameless stubbornness”.

“Like other enigmas… the story of a third man with two paymasters and four wives can never be definitively told, the case never closed,” said Jasper Rees in The Telegraph. “Hunting for the real Philby among the false fronts and double lives is like wandering around a maze uncertain if you’re looking for the entrance or the exit. From every new angle glint more questions.”

How was he eventually unmasked?

Ben Macintyre, whose book about Philby’s unmasking has been adapted as the ITV drama A Spy Among Friends, starring Guy Pearce and Damian Lewis, said in The Times that Solomon’s conversation with Victor Rothschild was “the moment that cracked the Philby case”.

For 24 years she “held tight to one of the greatest secrets of the 20th century: she knew that Kim Philby was a KGB spy”, Macintyre said. “Had she revealed this fact earlier, she might have saved hundreds and perhaps thousands of lives, averted the scandal of the Cambridge spy ring and prevented the collective nervous breakdown that gripped British intelligence when Philby defected to Moscow.”

Long-time colleague and friend Nicholas Elliott was sent to Beirut to confront Philby with Solomon’s evidence and their confrontation is depicted in A Spy Among Friends, with Philby giving everyone the slip before making his way to Moscow.

He died in Moscow in 1988 just before the collapse of the communist system he had spent his life serving.

What was his role in the Cold War?

Philby was “a crucial point of contact with the CIA, all the while stealing secrets for the KGB”, said Sky History. It is believed he shared tens of thousands of classified documents with his Soviet handlers over the course of his career.

In 2016, previously unseen footage from 1981 emerged of Philby, by then a retired colonel in the KGB, giving a secret lecture to officers of the Stasi, the East German intelligence service.

In it he described how he betrayed an operation to secretly send thousands of Albanians back into their country to overthrow the communist regime, “one episode which is usually cited to illustrate the human cost of Philby’s treachery”, said the BBC.

Many were killed directly because of his actions, but in his lecture Philby claims if he had not compromised the operation and it had succeeded, the CIA and MI6 would have tried it again in countries like Bulgaria, eventually leading to all-out war with the Soviet Union.

The news that Philby had been spying for the Russians “sounded an alarm in Whitehall”, said The Guardian, and “prompted a government campaign to minimise political embarrassment and prevent his memoirs being published”, according to secret files released in 2020.

It concerned the identity of a fourth member of the Cambridge spy ring, Sir Anthony Blunt, who had been uncovered as a Russian mole in 1964 when he held the role of surveyor of the Queen’s pictures. He was not publicly outed until 1979.