Why are there so many new Omicron sub-variants?

Latest sub-variants of Covid-19 mutation are fuelling fresh waves of infections worldwide

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Biology experts Sebastian Duchene and Ash Porter on whether the virus is mutating faster and the implications for the future of Covid

By now, many of us will be familiar with the Omicron variant of Sars-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid. This variant of concern has changed the course of the pandemic, leading to a dramatic rise in cases around the world.

We are also increasingly hearing about new Omicron sub-variants with names such as BA.2, BA.4 and now BA.5. The concern is these sub-variants may lead to people becoming reinfected, leading to another rise in cases.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why are we seeing more of these new sub-variants? Is the virus mutating faster? And what are the implications for the future of Covid?

Why are there so many types of Omicron?

All viruses, Sars-CoV-2 included, mutate constantly. The vast majority of mutations have little to no effect on the ability of the virus to transmit from one person to another or to cause severe disease.

When a virus accumulates a substantial number of mutations, it’s considered a different lineage (somewhat like a different branch on a family tree). But a viral lineage is not labelled a variant until it has accumulated several unique mutations known to enhance the ability of the virus to transmit and/or cause more severe disease.

This was the case for the BA lineage (sometimes known as B.1.1.529) the World Health Organization labelled Omicron. Omicron has spread rapidly, representing almost all current cases with genomes sequenced globally.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Because Omicron has spread swiftly, and has had many opportunities to mutate, it has also acquired specific mutations of its own. These have given rise to several sub-lineages, or sub-variants.

The first two were labelled BA.1 and BA.2. The current list now also includes BA.1.1, BA.3, BA.4 and BA.5.

We did see sub-variants of earlier versions of the virus, such as Delta. However, Omicron has outcompeted these, potentially because of its increased transmissibility. So sub-variants of earlier viral variants are much less common today and there is less emphasis in tracking them.

Why are the sub-variants a big deal?

There is evidence these Omicron sub-variants – specifically BA.4 and BA.5 – are particularly effective at reinfecting people with previous infections from BA.1 or other lineages. There is also concern these sub-variants may infect people who have been vaccinated.

So we expect to see a rapid rise in Covid cases in the coming weeks and months due to reinfections, which we are already seeing in South Africa.

However, recent research suggests a third dose of the Covid vaccine is the most effective way to slow the spread of Omicron (including sub-variants) and prevent Covid-associated hospital admissions.

Recently, BA.2.12.1, has also drawn attention because it has been spreading rapidly in the United States and was recently detected in wastewater in Australia. Alarmingly, even if someone has been infected with the Omicron sub-variant BA.1, re-infection is still possible with sub-lineages of BA.2, BA.4 and BA.5 due to their capacity to evade immune responses.

Is the virus mutating faster?

You’d think Sars-CoV-2 is a super-speedy front-runner when it comes to mutations. But the virus actually mutates relatively slowly. Influenza viruses, for example, mutate at least four times faster.

Sars-CoV-2 does, however, have “mutational sprints” for short periods of time, our research shows. During one of these sprints, the virus can mutate four-fold faster than normal for a few weeks.

After such sprints, the lineage has more mutations, some of which may provide an advantage over other lineages. Examples include mutations that can help the virus become more transmissible, cause more severe disease, or evade our immune response, and thus we have new variants emerging.

Why the virus undergoes mutational sprints that lead to the emergence of variants is unclear. But there are two main theories about the origins of Omicron and how it accumulated so many mutations.

First, the virus could have evolved in chronic (prolonged) infections in people who are immunosuppressed (have a weakened immune system).

Second, the virus could have “jumped” to another species, before infecting humans again.

What other tricks does the virus have?

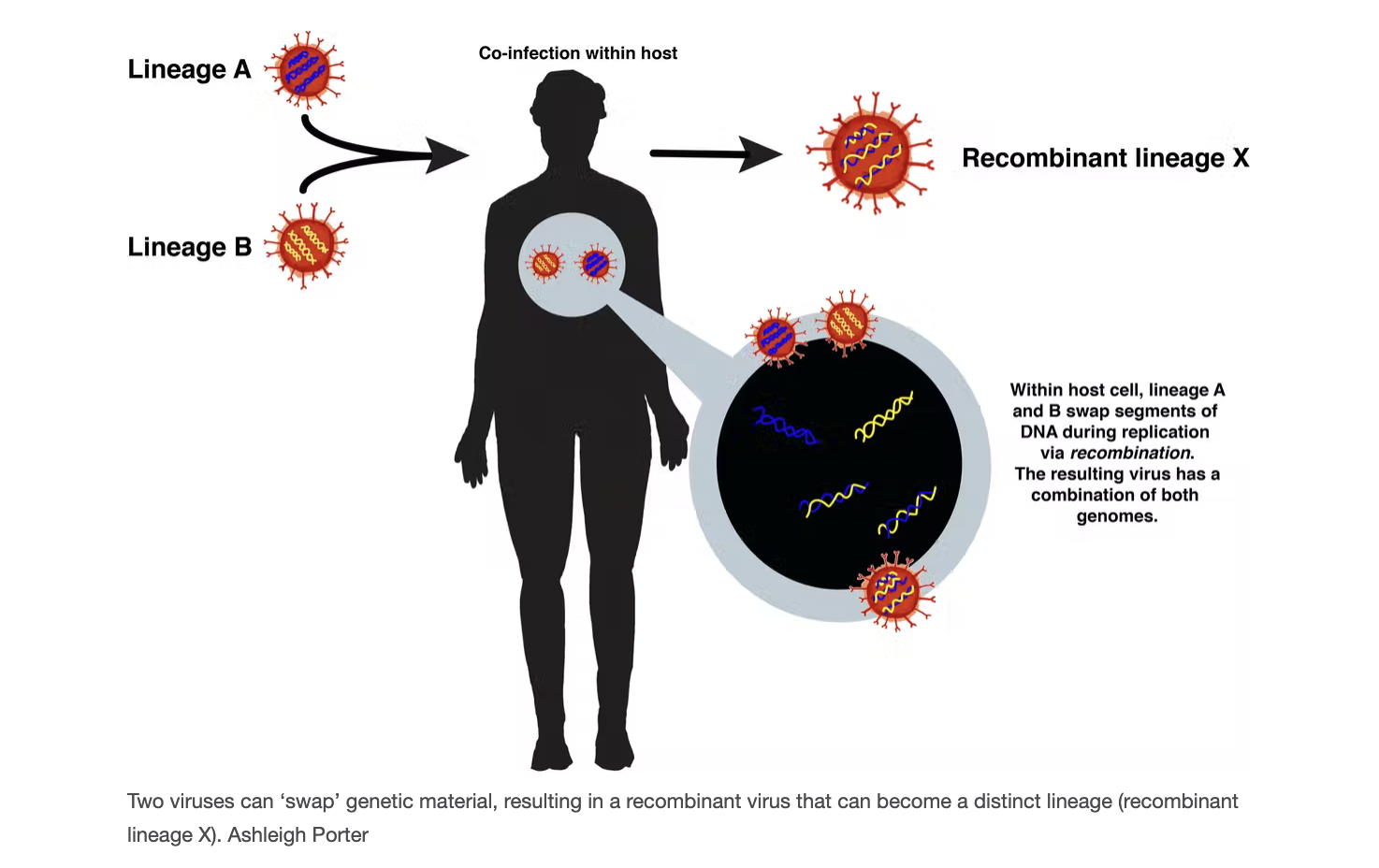

Mutation is not the only way variants can emerge. The Omicron XE variant appears to have resulted from a recombination event. This is where a single patient was infected with BA.1 and BA.2 at the same time. This coinfection led to a “genome swap” and a hybrid variant.

Other instances of recombination in Sars-CoV-2 have been reported between Delta and Omicron, resulting in what’s been dubbed Deltacron.

So far, recombinants do not appear to have higher transmissibility or cause more severe outcomes. But this could change rapidly with new recombinants. So scientists are closely monitoring them.

What might we see in the future?

As long as the virus is circulating, we will continue to see new virus lineages and variants. As Omicron is the most common variant currently, it is likely we will see more Omicron sub-variants, and potentially, even recombinant lineages.

Scientists will continue to track new mutations and recombination events (particularly with sub-variants). They will also use genomic technologies to predict how these might occur and any effect they may have on the behaviour of the virus.

This knowledge will help us limit the spread and impact of variants and sub-variants. It will also guide the development of vaccines effective against multiple or specific variants.

Sebastian Duchene, ARC DECRA fellow, The University of Melbourne, and Ash Porter, research officer, The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

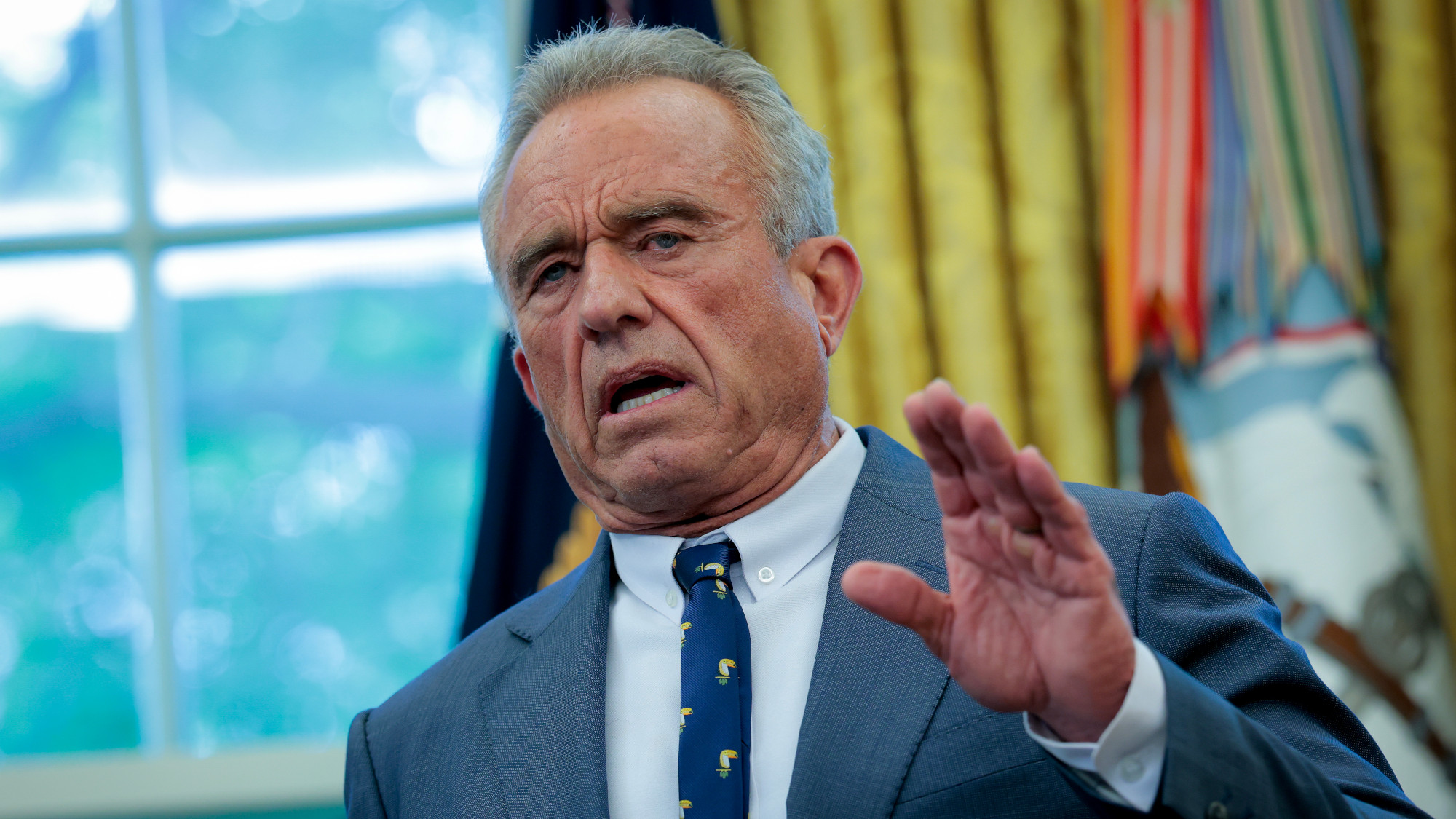

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics