Cloud seeding: how China plans to end drought with induced rainfall

The effectiveness of the controversial weather modification tool has long been in doubt

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

China is planning to carry out “cloud seeding” – a form of weather modification that involves spraying chemicals on to clouds so they rain earlier – to try to save grain harvests after the country’s driest summer since records began in 1961.

Hundreds of thousands of hectares of farmland, particularly in China’s southern Sichuan and Chongqing provinces, have been impacted by continuously high temperatures, reported the Global Times, an English-language, state-run newspaper.

Local governments are preparing to spray what the publication described as “drought-resistant and water-retaining agent[s]” in areas “lacking irrigation and watering conditions”, but no details were given about how exactly or where this would be done.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

According to CNN, Beijing is planning to use cloud seeding to bring more rainfall to the Yangtze River, which has dried up in certain areas. However, some of the operations are currently on “standby” as cloud cover is “too thin” for the technique to be effective.

How does cloud seeding work?

Cloud seeding is a decades-old weather modification tool that involves using aircraft, rockets or drones to release materials including silver iodide – which has a similar structure to ice – into clouds. This catalyses the process “by which water droplets clump together and fall as rain”, explained Vice.

The practice has been used “to prevent large storm surges by breaking up clouds” and, in the US, as a military technique “that’s since been banned by the United Nations, although its effectiveness in war was in doubt even in the 1970s”, added the site.

Not much is known about the larger environmental risks of cloud seeding, although there are concerns that people hundreds of miles away, or even in neighbouring countries, could be affected by “changes to rainfall and potentially deprived of important precipitation”, said The Washington Post.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What are its limitations?

“Great advances” have been made in cloud seeding techniques since it was first practised in the 1940s, but the ability to alter weather conditions “at will” remains limited, said YourWeather.co.uk. To ensure success, certain uncontrollable conditions have to be met concerning the types of clouds and the state of the atmosphere.

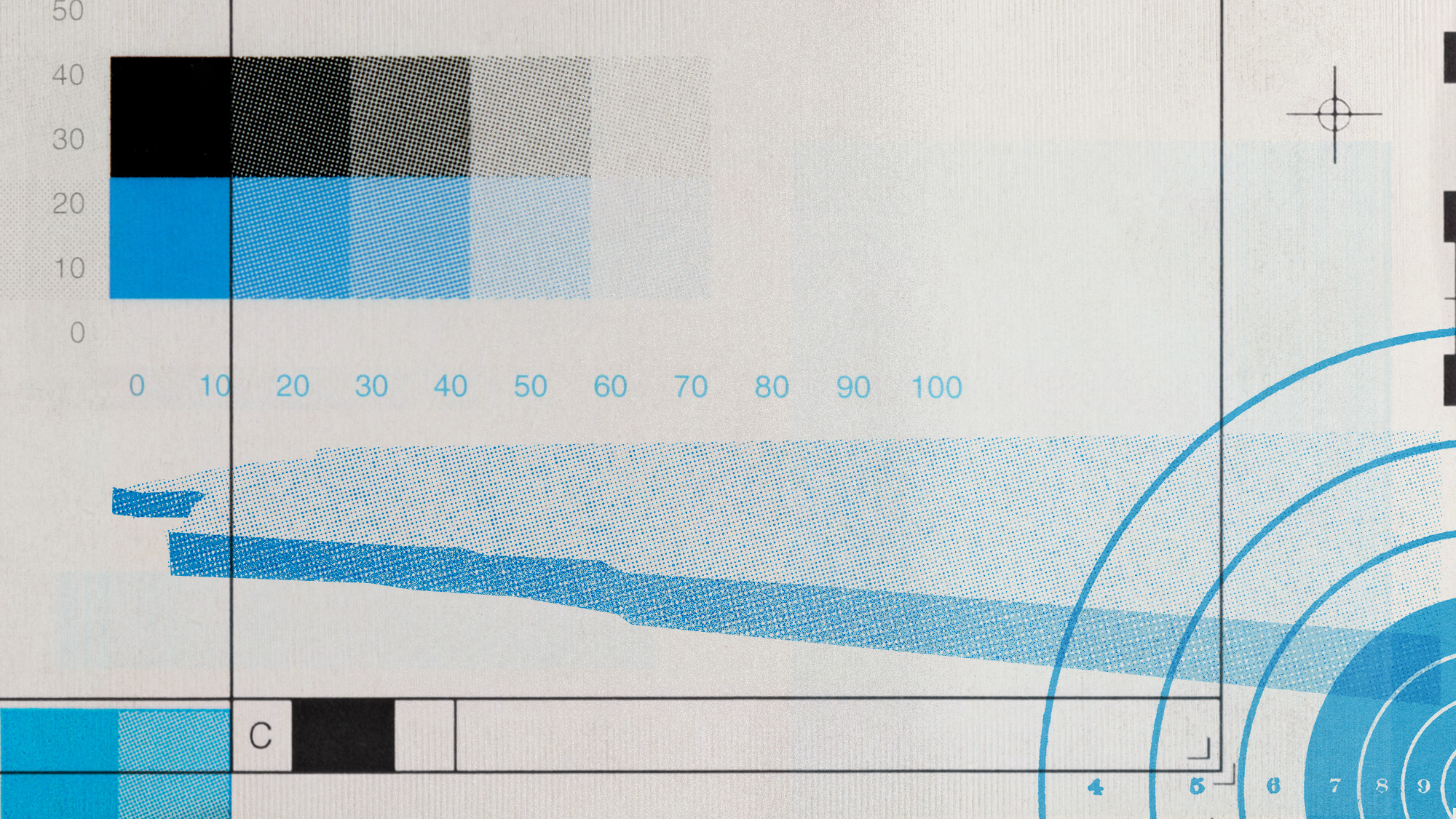

It is also extremely expensive, with Smithsonian magazine reporting that a US-based cloud seeding programme could cost “$27 to $214 per acre-foot of water in a low-cost scenario and $53 to $427 per acre-foot in a high-cost scenario”.

“Cloud-seeding has always been something for people who have more money than sense,” Gavin Schmidt, a senior adviser on climate at Nasa, told The Washington Post earlier this year. “It’s a very big spend with probably not a lot to show for it.”

Is it effective?

Despite “decades” of cloud seeding operations, including by militaries and civilian governments, evidence that the practice works outside miniature lab-created clouds “has been elusive”, reported Science.org in 2018. This is partly because the “chaotic” nature of weather has made “controlled, natural experiments almost impossible”.

But that same year, there was a breakthrough when researchers in Idaho proved “for the first time outside the lab, that humans can artificially turbocharge snowfall”. The team used cloud measuring equipment to detect snowflakes growing from “a few microns in diameter to 8 millimetres in diameter – heavy enough to fall to the ground” after two small planes dropped canisters that spread silver iodide into a group of clouds.

“We were super, super excited. Nobody had seen that before,” said Katja Friedrich, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Colorado in Boulder, who was part of the experiment.

Which countries have used it?

China has “long attempted to modify the weather through cloud-seeding”, said The Washington Post, with “tens of thousands” of people working for the Beijing Weather Modification Office and other provincial organisations.

Famous examples of Beijing using the technology include the 2008 Summer Olympics, when rockets were fired at clouds “to prevent them from reaching the skies over the open-air Bird’s Nest the night of the opening ceremonies”, and in summer 2021 when the government sent rockets to clear the air over the “polluted and overcast” capital ahead of the Communist Party centenary gathering – a gambit known as “blueskying”.

But it’s not just China that has attempted to play God with the weather. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been cloud seeding since the 1990s and conducted at least 185 cloud seeding operations in 2019 alone, reported Wired magazine.

That year saw “torrential downpours” in a country “rarely associated with rain”, with people “wading through streets, workers pumping water from a flooded residential area, and rainwater flowing down escalators at the world-famous Dubai Mall”.

And, in March 2021, The Guardian reported that the “stresses of drought, upon water supplies for drinking and to supply the west’s vast agricultural systems”, had prompted eight US states, including the “four corners” states of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico, to look to cloud seeding to “stave off the worst”.

Cloud seeding is an “encouraged technology for Wyoming to use based on our drought contingency plan”, said Julie Gondzar, project manager for the state’s water development office. “It is an inexpensive way to help add water to our basins, in small, incremental amounts over long periods of time.”

Is it viable for other countries facing drought?

Although it can help lessen the impact of drought, cloud seeding doesn’t solve its “systematic causes”, said The Guardian. The technique “needs to be part of a broader water plan that involves conserving water efficiently, we can’t just focus on one thing”, Friedrich told the paper last year.

Indeed, said The Independent, “encouraging more precipitation in one area won’t do enough on its own to end the mega-drought striking the west, or to impact the underlying climate crisis”. There is also a political risk, as countries could end up accusing each other of stealing their water.

But, despite its controversy, “cloud-seeding looks set to become a major part of the climate-fighting agenda”.

Kate Samuelson is The Week's former newsletter editor. She was also a regular guest on award-winning podcast The Week Unwrapped. Kate's career as a journalist began on the MailOnline graduate training scheme, which involved stints as a reporter at the South West News Service's office in Cambridge and the Liverpool Echo. She moved from MailOnline to Time magazine's satellite office in London, where she covered current affairs and culture for both the print mag and website. Before joining The Week, Kate worked at ActionAid UK, where she led the planning and delivery of all content gathering trips, from Bangladesh to Brazil. She is passionate about women's rights and using her skills as a journalist to highlight underrepresented communities. Alongside her staff roles, Kate has written for various magazines and newspapers including Stylist, Metro.co.uk, The Guardian and the i news site. She is also the founder and editor of Cheapskate London, an award-winning weekly newsletter that curates the best free events with the aim of making the capital more accessible.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures