Climate change in the Alps: is this the end of skiing?

The long-term viability of many ski resorts is being threatened by rising global temperatures

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A very warm start to the year wrought havoc for Europe’s skiing industry. Around half the slopes in France were forced to close due to lack of snow; winter sports competitions were cancelled; skiers were left clamouring for refunds.

Over the New Year weekend, the Swiss Alps recorded their highest-ever January temperatures, and heavy rain wiped away what snow there was. Resorts accustomed to temperatures of -10°C at that time of year were recording 18°C, and skiers at lower altitudes had to make do, at best, with skinny slivers of artificial snow.

Heavy snowfall last week has improved conditions for the time being, but the long-term prospects look bleak for many of Europe’s resorts.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How bad is the problem?

The Alps, which host more than a third of the world’s ski resorts, are particularly sensitive to global warming. The climate there has already changed radically over the past century, with temperatures rising by 2°C, about twice the global average.

Snow depth has reduced by nearly 10% since the 1970s, and “snow cover duration” by more than 5% per decade over the past 50 years. The ski season is now a month shorter than in the 1970s, and the snowline – the altitude at which rain turns to snow – has risen.

Back in 2007, the OECD found that nearly 10% of 666 Alpine ski areas in Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland already no longer had reliable snow. And since then, the situation has got much worse.

No summer skiing took place in Val d’Isère in France last year for the first time since 1958. According to a study by the Grenoble Alpes University, about 80 European ski resorts have closed in recent decades due to a lack of snow.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How do resorts manage the lack of snow?

Many rely heavily on snow cannons, which blast water droplets into the cold air, freezing them. Laax in the Swiss Alps, for instance, has 430 snow machines for its 200km of ski runs. However, snowmaking requires a lot of water and energy - albeit recycled water and regionally sourced renewable energy in Laax’s case. A Swedish study found that the electricity used to make just two metres cubed of artificial snow is, on average, equivalent to what a typical British household would use in a day.

And it takes about 285,000 litres of water to create a 15cm blanket of snow covering an area of just 61 square metres. This is problematic in regions that are already at risk of drought because of lowered snowfall, and it can require the creation of artificial lakes in ecologically valuable and vulnerable areas. The process is very expensive, and at times this year it hasn’t been possible to make artificial snow because sub-zero temperatures are required; besides, skiers prefer natural snow.

What else can resorts do?

Some are already making attempts to pivot to activities other than traditional winter sports, rebranding themselves as year-round destinations, with spas and activities including hiking, mountain biking, snow-free tobogganing and ice climbing. But it’s an incomplete solution, because skiers – who buy expensive lift passes and will often rent equipment – bring in much more money than hikers and cyclists do; and without skiing there is little to draw people to the mountains in winter.

The fact is, skiing is big business: Alpine ski resorts receive up to 80 million tourists per year and turn over nearly €30bn in revenue; in France, about half-a-million jobs are dependent on the industry.

How bad will it get?

It looks very bad. A Swiss study from 2017 estimated that, depending on how much global carbon emissions are reduced by, snow cover in the Alps will decline by 30% to 70% by the end of this century.

The OECD has estimated that only around 400 of 666 Alpine ski areas would be “snow reliable” if global temperatures were to rise by 2°C – the limit theoretically set by the Paris climate change agreement – and only 200 if the temperature were to rise by 4°C.

“Any resort below 1,500m probably doesn’t have a future in the winter,” says Christine Ferrière, deputy manager of the Savoie Mont Blanc group of French resorts; the majority of Alpine resorts are below that level. Métabief in France’s sub-Alpine Jura is anticipating that its last ski season will be in the early 2030s.

What about resorts in the rest of the world?

They are facing similar trends, but with local variations. Many resorts in the North American Rockies are protected by colder temperatures and higher elevations, but even so, the April snowpack in US western states declined at 86% of the sites measured between 1955 and 2020, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency; and resorts from California to Maine are reporting shorter ski seasons.

Scandinavian areas are also predicting a shortening of ski seasons. In early 2020, many of Japan’s resorts, which are known for their high-quality powder snow, had to close because the northern part of the country had little more than a third of its average snowfall in December.

Does this matter?

For non-skiers, the fate of a few resorts catering to the rich might not be at the top of their list of climate change concerns, particularly given the heavy carbon footprint of a sport that usually involves plane travel, as well as energy-hungry lifts, “piste-basher” machines and snow cannons.

However, many resorts – canaries in the coalmine of a warming world – are making great efforts to become sustainable, cutting energy consumption and using carbon-neutral energy sources.

Unfortunately for less well-off skiers, the sport will become more expensive and more exclusive as snow cover shrinks. And for the economies of the areas affected, it spells devastation. Didier Thévenet, the mayor of the village of La Clusaz in France, recently told The Washington Post: “We will have less money, and we will probably lower our standard of living.”

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

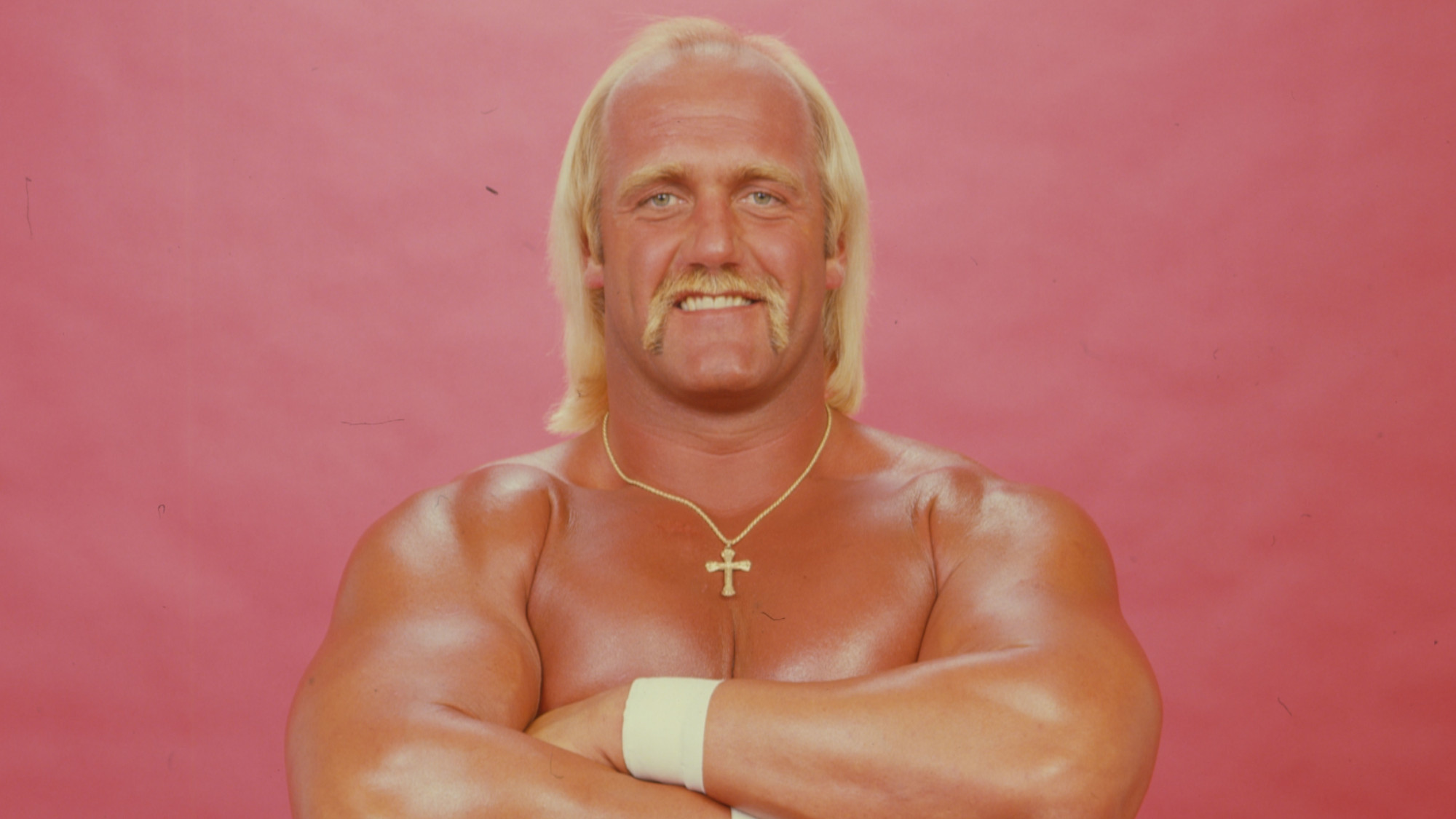

Hulk Hogan

Hulk HoganFeature The pro wrestler who turned heel in art and life

-

Cricket's crackdown on 'monster' bats

Cricket's crackdown on 'monster' batsIn the Spotlight Indian Premier League has introduced on-pitch checks to ensure bats meet strict size limits

-

The Masters: Rory McIlroy finally banishes his demons

The Masters: Rory McIlroy finally banishes his demonsIn the Spotlight McIlroy's grand slam triumph will go down as 'one of the greatest and most courageous victories in the history of golf'

-

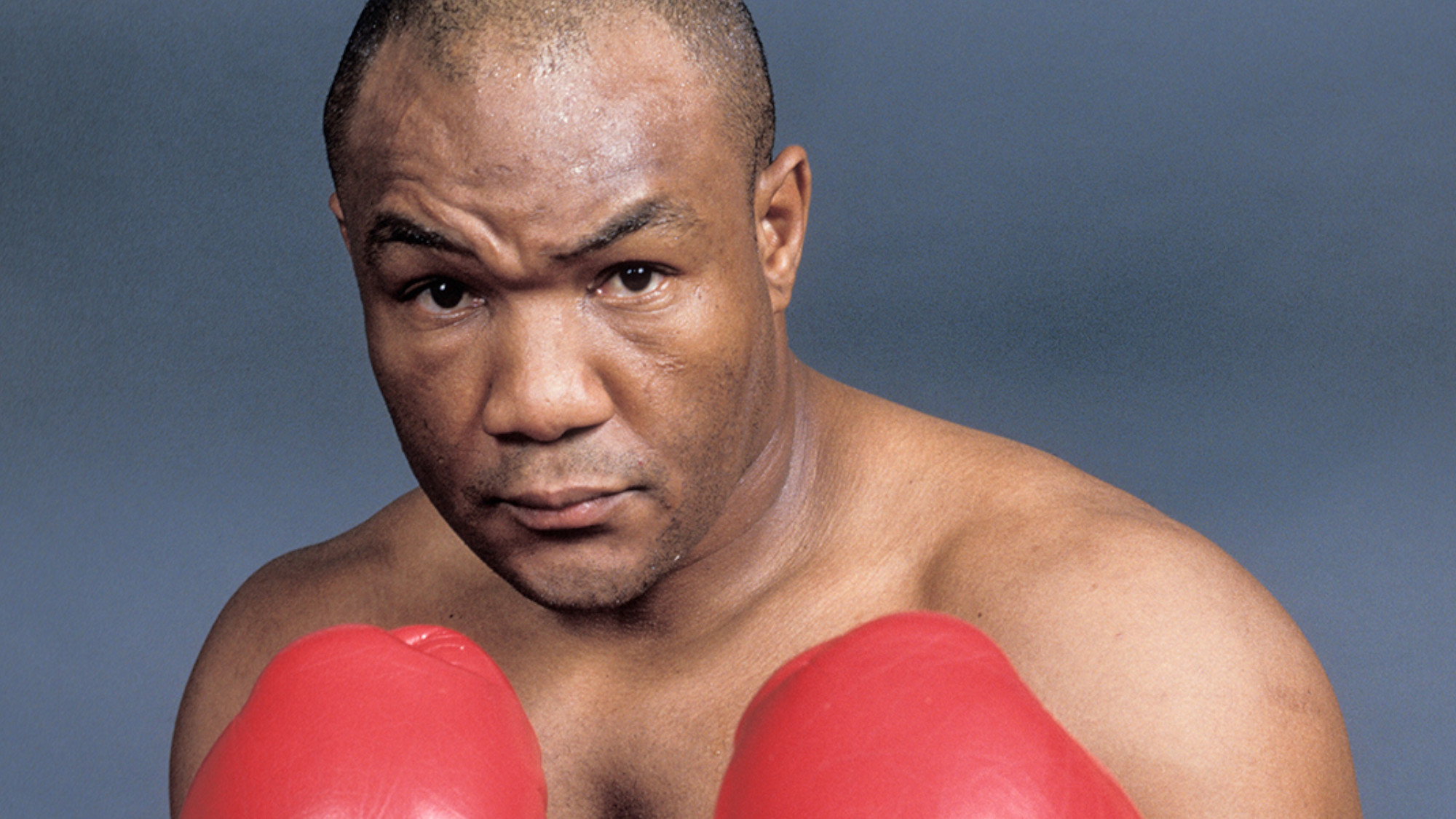

George Foreman: The boxing champ who reinvented home grills

George Foreman: The boxing champ who reinvented home grillsFeature He helped define boxing’s golden era

-

Why Jannik Sinner's ban has divided the tennis world

Why Jannik Sinner's ban has divided the tennis worldIn the Spotlight The timing of the suspension handed down to the world's best male tennis player has been met with scepticism

-

When 'a kiss is not a kiss': Spanish football on trial

When 'a kiss is not a kiss': Spanish football on trialTalking Point Luis Rubiales faces up to two-and-a-half years in jail if convicted of sexually assaulting footballer Jenni Hermoso