Guatemala’s anti-corruption election winner offering hope to a region

Central Americans fighting authoritarianism ‘rooting’ for centre-left Bernardo Arévalo

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

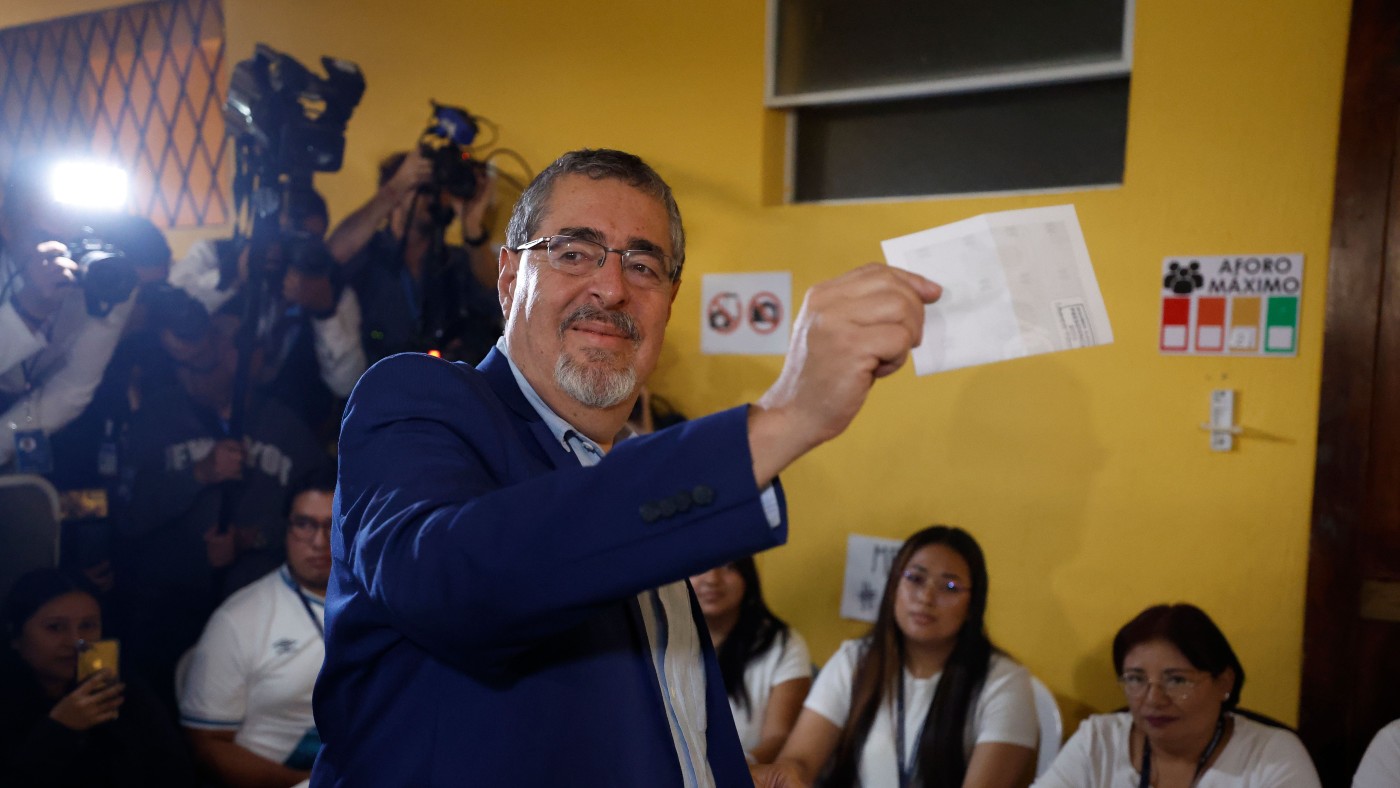

An anti-corruption campaigner and son of the country’s former president has won an “impossible” election victory in Guatemala, in what onlookers hope is a watershed moment for democracy in the beleaguered region.

The centre-left Bernardo Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla (Seed Movement) party beat former first lady Sandra Torres, candidate for the National Unity of Hope (UNE), with 58% of the vote to 37%.

It was “a victory that until recently seemed impossible”, said the Buenos Aires Herald, amid judicial efforts to block Arévalo from the run-off after he shocked the nation by finishing second in the first round of voting. In a country with “unstable democratic institutions”, serious inequality, poverty and violence, said Vox, his success “seems like a revelation”.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The son of Guatemala’s first democratically elected president, Juan José Arévalo, his victory “represents a potent repudiation” of corruption and “democratic erosion”, said The Guardian, and “stands in stark contrast to the bleak situation in El Salvador and Nicaragua”.

Fellow democrats in Central America are “rooting” for Guatemala’s emergent civic movement, said The New York Times, “which could provide a blueprint for efforts to resist their own increasingly autocratic leaders”.

Who is Bernardo Arévalo?

Arévalo is “the least populist guy you can imagine”, Will Freeman, a Latin America fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told USA Today. He is “painfully devoid of slogans”, but strikes a chord by “being sincere and sticking to his academic roots”.

Arévalo’s “distinguishing” characteristic is that “he’s just an outsider”, Freeman told the Financial Times (FT), without alliances to “other tainted factions”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The “calm” man was born in Uruguay, “when his parents were exiled from their native land”, said El País. His father, Juan José Arévalo, was the beloved president behind Guatemala’s nascent democracy in the 1940s, known as the Democratic Spring. It ended violently when his successor was overthrown by the CIA-backed coup in 1954, leading to civil war and four decades of repression and economic stagnation.

The Seed Movement emerged in the heat of protests that “convulsed” the country in 2015, known as the Guatemalan Spring. The UN-backed organisation known as CICIG (International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala) exposed widespread political corruption, in a scandal that forced President Otto Pérez Molina’s resignation. The Seed Movement formed as a political party in 2018.

The sociologist and former diplomat “appealed to voters angry at the influence over the state exercised by a sprawling network of political, military and economic elites,” said The Economist, with ties to organised crime, which Guatemalans call “the pact of the corrupt”.

What happened in the elections?

In anticipation of the elections, the president “packed the courts and the electoral tribunal with loyalists”, wrote Guatemala experts Anita Isaacs, Rachel A. Schwartz and Alvaro Montenegro in an essay for The New York Times in July. The regime then “enlisted these entities to distort the Constitution and tamper with election procedures to tilt the political playing field in their favour”.

The Supreme Electoral Tribunal barred three popular candidates from running for election, on “manufactured charges of malfeasance”, “paving the way for Arévalo”.

Despite polling at 3% before the elections, according to Prensa Libre, Arévalo finished second in the first round of voting on 25 June, with just under 12% of the vote.

Torres and her allies challenged the results, and in July, the country’s top court froze certification of the first-round results, ordering the ballots to be reviewed. The “topsy-turvy election” was “thrown into further turmoil”, said USA Today, when the attorney general’s office raided the electoral authority office in July.

Rafael Curruchiche, a “controversial” special prosecutor in the attorney general’s office, temporarily suspended Arévalo’s party amid “thin” accusations of vote-counting irregularities. He also claimed that the Seed Movement party illegally collected false signatures when it established itself. Both Curruchiche and the attorney general, Consuelo Porras, have been sanctioned by the US and accused of corruption.

The move “drew swift calls for Guatemalans to take to the streets in protest”, and warnings from Western officials about threats to democracy.

Independent election monitors, the Organization of American States (OAS), concluded that there was “no reason to suspect that there were irregularities”. The EU, which monitored the vote, called the electoral process the “clearly manifested will of citizens”.

What next?

The outgoing president, conservative Alejandro Giammattei, congratulated Arévalo and invited him to start the transition in January. The elections were carried out “in peace, with few isolated incidents”, Giammattei posted on Twitter.

But Arévalo will face “an uphill battle in governing”, said the FT, with his party holding only 23 out of 160 Congress seats, “forcing it to forge alliances or a coalition to pass legislation”.

Whatever happens could have “a decisive impact” in a region “so closely tied to the United States and key to securing the southern border”, said USA Today. More than 220,000 Guatemalans entered the US via the Mexico border in 2022, according to Border Patrol figures – more than any other Central American country.

As demonstrated by Gabriel Boric in Chile or Gustavo Petro in Colombia, said El País, “the task of governing on the basis of hope and change isn’t so simple”.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.