The politics of loneliness is totalitarian

What Hannah Arendt would say about all the lonely people

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Friendlessness is on the rise — and so, one must presume, is loneliness.

That's the troubling takeaway from a study released last week by the Survey Center on American Life that shows the number of both men and women who claim to have "no close friends" increasing five-fold over the past 30 years. For men, the rate of friendlessness has gone from 3 percent in 1990 to 15 percent in 2021, and for women from 2 percent to 10 percent today. The pattern is the same on the high end, with the percentage of men saying they have 10 or more friends dropping from 40 to 15 percent and the percentage of women saying the same falling from 28 to 11 percent.

However you cut it, this is bad.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's bad for the lonely, isolated individuals themselves, because having close ties to other people is strongly correlated with various markers of physical and mental health. Without such ties, individuals tend to grow unhappy and unhealthy and can even sink into depression.

But it's also a bad sign for our country and our society, culture, and economy, since it could mean that we're developing in a direction that will make more of us lonelier and more isolated. That is bound to lead to deep and increasingly widespread discontent with our way of life.

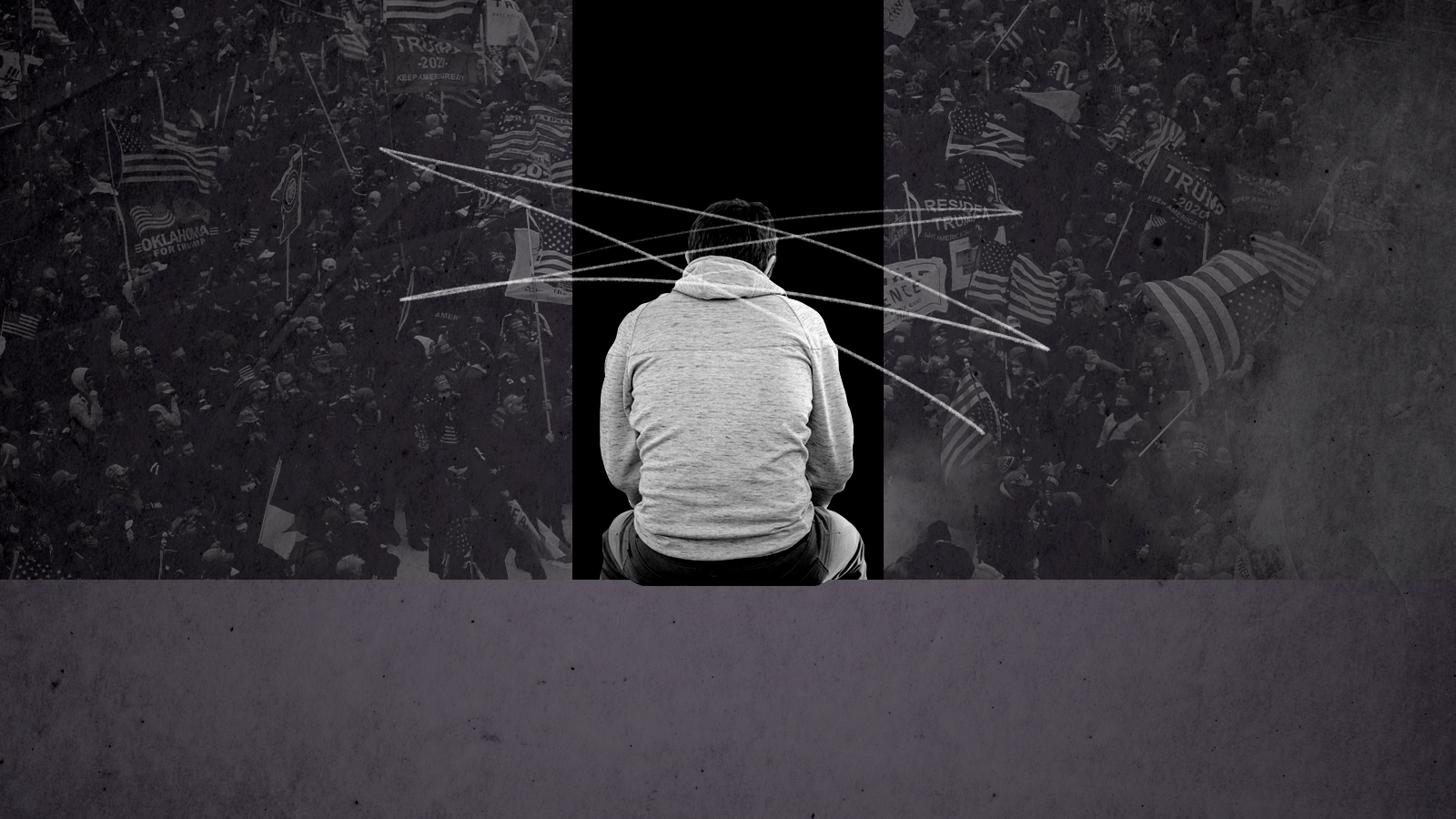

And that brings us to the most ominous thing of all about rising rates of friendlessness: It provides a potent (if probably only partial) sociological explanation for why our politics have become much more polarized in recent decades, with increasing numbers of people attracted to more radical forms of political dissent on both the right and the left. It also suggests that if the loneliness and isolation become worse, so could our political pathologies.

Human beings are social, communal creatures. We seek out connection with others of our kind and especially enjoy engaging in common enterprises and the emotional intimacy that can follow from such experiences. The standard way for people to have these kinds of collective experiences is out in the world — in extended family, local community, religious organizations, work, unions, clubs, and politics.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The fact that friendlessness is on the rise seems to be a function, in part, of the wasting away of these intermediary institutions in civil society. Families are smaller than they used to be, and fewer people marry in the first place. Communities are fraying under economic pressures and as a result of social shifts. Fewer people go to church. Work more often involves analysis of symbols (ideas and numbers) and takes place mostly within our own heads, mediated by technology, with remote work also becoming more common in recent years. Unions are a shadow of what they once were. We've been bowling alone for decades.

All of this can make it harder to forge friendships. At least in the real world.

The rise of the internet, and especially social media, has opened up other possibilities for social interaction, if not exactly friendships. People sharing similar interests, hobbies, quirks, and obsessions can easily find each other online and enjoy a digital facsimile of friendship with others. These virtual communities are more like collective groups of topic-specific pen pals than real-world friendships. The latter are marked both by physical closeness (involving handshakes, hugs, backslaps, shared meals and drinks, and all the intimacy that accompanies them) and the possibility of holistic self-exposure beyond the specific endeavor that initially brought the friends together. Whether you and your friend originally became close playing or watching sports, shopping, or participating in a book club, that foundation can open up the possibility of a deeper or broader sharing of memories, thoughts, hopes, and fears — the full stories of our lives.

Online relationships are different. A modicum of that closeness might be achieved by some, taking the edge off the pain and loneliness of a life without friends. But for most the interaction will tend to remain topic-specific — and for nearly all, the interaction will be entirely mental. A friendship (or love affair, for that matter) conducted completely online takes place wholly within the minds of the participants, with imagination playing a vastly greater role than it would in the real world. That's one reason why the quirks and obsessions that draw people to specific websites, chat rooms, Facebook groups, and Twitter threads often lead those clusters to become quirkier and more obsessive over time. Lacking any need to test ideas against the hard limits and constraints that obtain in the physical world, ideas can run wild in the minds of participants in an online conversation or debate.

This is especially so when it comes to politics.

It's one thing to keep an online community together based on a common love — of Star Trek, or Taylor Swift, or NBA basketball, or whatever. It's quite another to root it in common hatreds. Antagonism to out-groups helps to add cohesion to any collective. Add in the high ideals and impulse toward noble sacrifice that political discussion tends to call forth in those who participate in it and we're left with a very potent form of online association — one that can grant its members more fulfillment and satisfaction than almost any other kind.

A nation of increasingly lonely, friendless citizens given outlets to find collective, communal fulfillment online will be a nation spawning a range of radical political factions, groups, or movements defined by and drawing the bulk of their cohesion from their loathing of other factions, groups, or movements. The list of potential enemies is long: Billionaires, Black people, white women, Republicans, Trump supporters, immigrants, liberals, Muslims, socialists, Jews, communists, fascists. For many, this collective hatred will remain in the mind, like a virtual-reality political shooter game. But because the hatreds concern the real world, and the people engaged in such collective antagonism actually exist in that world, there's always a risk of this radicalism spilling out into the country itself.

As we saw on Jan. 6.

One political thinker who would have been thoroughly unsurprised about these developments is Hannah Arendt, the great analyst and theoretician of totalitarianism. In her view, totalitarianism is a novel form of government for which the men and women of modern Europe were prepared by "the fact that loneliness … ha[d] become an everyday experience" for so many. The all-pervasive system of the totalitarian regime promised and, for a time, provided an all-encompassing orientation, meaning, and purpose for the masses that they otherwise lacked and craved in their lives.

Where our situation differs from the totalitarian systems of the mid 20th century that were exemplars for Arendt is that we are deeply, perhaps hopelessly, divided. No part of our nation can hope to provide the whole with a unifying, galvanizing purpose to liberate us from our loneliness. Instead, each faction has forged its own world online. That points in another direction — toward increasing centrifugal forces, rising factional polarization, and the growing risk of additional events like the insurrection on Capitol Hill nearly six months ago.

It might seem strange that the absence of friendship in the lives of individual men and women could be paving the way for the gravest forms of political misfortune. But human beings have needs that can only be described as spiritual. Loneliness can be intolerable — so much so that even the most toxic forms of political association begin to look like a godsend.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Magazine solutions - February 27, 2026

Magazine solutions - February 27, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine solutions - February 27, 2026

-

Magazine printables - February 27, 2026

Magazine printables - February 27, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - February 27, 2026

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred