The Democrats' new cult of the popular

Why 'talk about popular issues' is not the magic answer the party is looking for

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How should the Democratic Party position itself to win? One option embraced by a faction of the party is to become "shorpilled," referring to the contrarian data guru David Shor. He advocates a position that writer Aaron Freedman intelligibly dubbed "survey liberalism," which Shor has explained this way: "You should put your money in cheap media markets in close states close to the election, and you should talk about popular issues, and not talk about unpopular issues."

Concretely, that means placating the racism of white voters, avoiding slogans like "defund the police," being cautious on immigration reform, heavily means-testing welfare programs, and so on — basically the suite of policies moderate Democrats already support — because that's what polls say most voters like. Other prominent believers in this doctrine include writer Matt Yglesias, former President Barack Obama, and reportedly members of the Biden White House.

I am skeptical.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The first and most obvious problem with survey liberalism is that polling is a highly imprecise business. Many, many studies done from decades ago to the present day have demonstrated that slightly changing the wording of a poll, or which questions are included, or the order in which the questions are asked, can significantly alter results.

In the modern age, there is a further problem that getting accurate samples has gotten harder and harder. A pollster obviously cannot speak to every person in the country, so they use a statistically representative sample (and/or weight their results to adjust for the demographic background). This was fairly easy 30 years ago, but today, most people no longer have landlines, and few people answer unknown cell phone numbers anymore thanks to a constant deluge of spam calls. Polling firms have repeatedly overhauled their methodology in an attempt to account for this, but their budgets are not unlimited, accuracy is a moving target, and their recent record is not great. National forecasts were fairly close in both the 2020 and 2016 elections, but several state polls were quite badly off in both years, and in the same direction — each time underestimating Trump's support in critical swing states.

All this means that using polls to assemble a "popular" agenda is going to be biased by a substantial dose of random happenstance, even if you are being as scrupulous as possible.

In practice, scrupulousness is a rare commodity in politics. I don't doubt that the survey liberalism adherents are familiar with most if not all of the data I have cited so far. But as a famous repeat victim of Twitter hoaxes once wrote, "a man's at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with." All the ways that polls might be slanted or biased raises the possibility of cynical abuse (just rigging the questions to get what you want), or self-deception, as Shor himself says was true of the Hillary Clinton campaign. No matter how sure you are in your own head that you are being Mr. Data Professional, everyone who thinks and writes about politics has strong political views and that will inevitably color how they treat polls — there will always be a temptation to seize on (or commission) convenient polls, or ignore inconvenient ones. (I of course am guilty of this myself.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When Shor asserts that "the more you means-test a program the more popular it gets" — absurdly implying that the pandemic stimulus checks, which registered support from about three-quarters of Americans in multiple polls, would be even more popular if they went to only the single poorest person in the entire country — he's revealing how a contrarian delight in needling the left can lead to (at a minimum) ridiculous exaggeration. When Yglesias argues that Matt Damon would be a good political candidate because he was reported to have only recently stopped using homophobic slurs in a country where same-sex marriage polls at 70 percent approval (though Damon later denied the story), we see a heated dislike of identity-centered "wokeness" overriding common sense.

This isn't just about individuals, either. Consider Gallup, one of the oldest and most-reputable polling firms on earth. For years now it has been conducting a set of polls on Social Security that are wildly biased and ideological — smearing the program, implying it will disappear soon, and asking how benefits should be cut rather than if they should be cut at all. One poll has this prompt: "Next, I'm going to read a list of problems facing the country … How much do you personally worry about the Social Security system?" Another: "Which of these statements do you think best describes the Social Security system — it is in a state of crisis, it has major problems, it has minor problems or it does not have any problems?" Another: "How long do you think it will be until the costs of the Medicare and Social Security programs create a crisis for the federal government[?]"

This is because of a well-funded, decades-long neoliberal propaganda campaign to cut the program, explained well in an old Slate article by Yglesias, of all people. "Important People absolutely despise Social Security," he wrote, because "Taxing working people to hand out free money so people don't need to work is antithetical to the spirit of capitalism." Eventually the Gallup pollsters internalized the notion that Social Security is a problem as neutral and non-ideological, and started writing polls reflecting that thinking. (More welfare-friendly polls have naturally found much more positive results for Social Security.)

A similar abuse of polls and the rhetoric of political "realism" was a key part of the strategy neoliberals used to take control of the Democratic Party in the 1970s and 1980s. When George McGovern got smashed by Nixon in 1972, they declared that the New Deal was dead, and Democrats needed to pivot to the right to win. This argument was facially dubious — every Democratic presidential candidate who lost between 1980 and 1988 was some kind of neoliberal, yet somehow their ideas were not blamed for the loss — but when Bill Clinton finally won, they closed the rhetorical circuit. From that day forward the Democratic leadership has hectored its own base that leftist ideas are always unpopular and doomed (so as to keep them off the policy agenda) and that the most important characteristic by far in a politician is their ability to get elected.

In reality, no political party has ever been completely agenda-neutral and just done whatever is popular. As Matthew Stoller wrote in a book review about the neoliberal takeover: "Parties don't poll for good ideas, run races on them, and then govern. They have ideas, poll to find out how to sell those ideas, and run races and recruit candidates based on the polling."

This matters because how some policy proposal performs in the political vacuum of a single phone call from a stranger is a very different question than how it will perform when exposed to a national media debate. The most important factor there, of course, is the behavior of the right-wing propaganda machine. Conservative media is so good at lying that it has successfully convinced millions and millions of people not to take a safe, effective vaccine during the worst pandemic in a century. People are dying unnecessarily as a result.

The policies Democrats run on will face a coordinated attack from extremely loud and well-funded liars, no matter what they are. A once-popular agenda can easily fall far underwater under such an assault.

On the other hand, there is a liberal media as well (and a much smaller leftist media). While not nearly as unified, this also has a powerful effect on public opinion. There are more people who trust MSNBC, NPR, The Washington Post and The New York Times, and so on, than there are loyal Fox News and Newsmax watchers, though the attachment is not so strong. Moreover, anyone who has done a lot of door-to-door canvassing can tell you that a sizable portion of people do not have super well-formed views about complicated policy questions (or any views at all), and can quite easily be swayed one way or the other.

It follows that behavior of Democrats themselves (and their media allies) is nearly as important as the behavior of the right in shaping what is popular. Survey liberals sometimes point to the fact that leftist members of "the Squad" are considerably less popular than President Biden in their own districts as evidence for the unpopularity of their ideas. But this could be because they are routinely attacked and criticized by the party leadership, who are trusted implicitly by liberals. If Biden was constantly buddy-buddy with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and anointing her as a future party leader then she would likely be roughly as popular as he is, at least in her own heavily-blue district.

I don't blame Democratic elites for disagreeing with AOC's politics. I do blame them for heaping her with scorn and then passive-aggressively pointing to her relative unpopularity as being proof of her Bad Politics. It's the exact same dishonest 1990s strategy of hiding ideology behind polling results the very critics have helped produce.

The writer Osita Nwanevu has argued persuasively that the American left doesn't have a magic formula for victory. The polling on policies like Medicare-for-all is (no surprise) highly equivocal and contradictory. There's no guarantee that if Biden were to adopt that, or any other of Sen. Bernie Sanders' ideas, he would benefit at all.

But as Nwanevu also points out, it's much more certain that the left is correct about what is mechanically necessary to preserve American democracy. Recent reporting has shown ever more clearly that former President Donald Trump attempted an autogolpe after he lost the election — aside from the Jan. 6 putsch, he tried to convince his acting attorney general and deputy attorney general to "just say that the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me," as transcribed in the notes of the deputy. Meanwhile, Trump's acting head of the Department of Justice civil rights division also tried to convince the attorney general to overturn the election results in Georgia. The effort to stay in power only didn't succeed because a handful of key Republicans (most of whom have since been purged from the party) refused to go along with it. It would be idiotic to count on that happening again.

Today, famous conservatives have taken to praising Hungary (and the former conservative dictatorship in Portugal) because they are deeply attracted to the idea of a pseudo-democratic gangster state in which an extreme right-wing party holds permanent power, and liberals, leftists, and minority groups face state persecution.

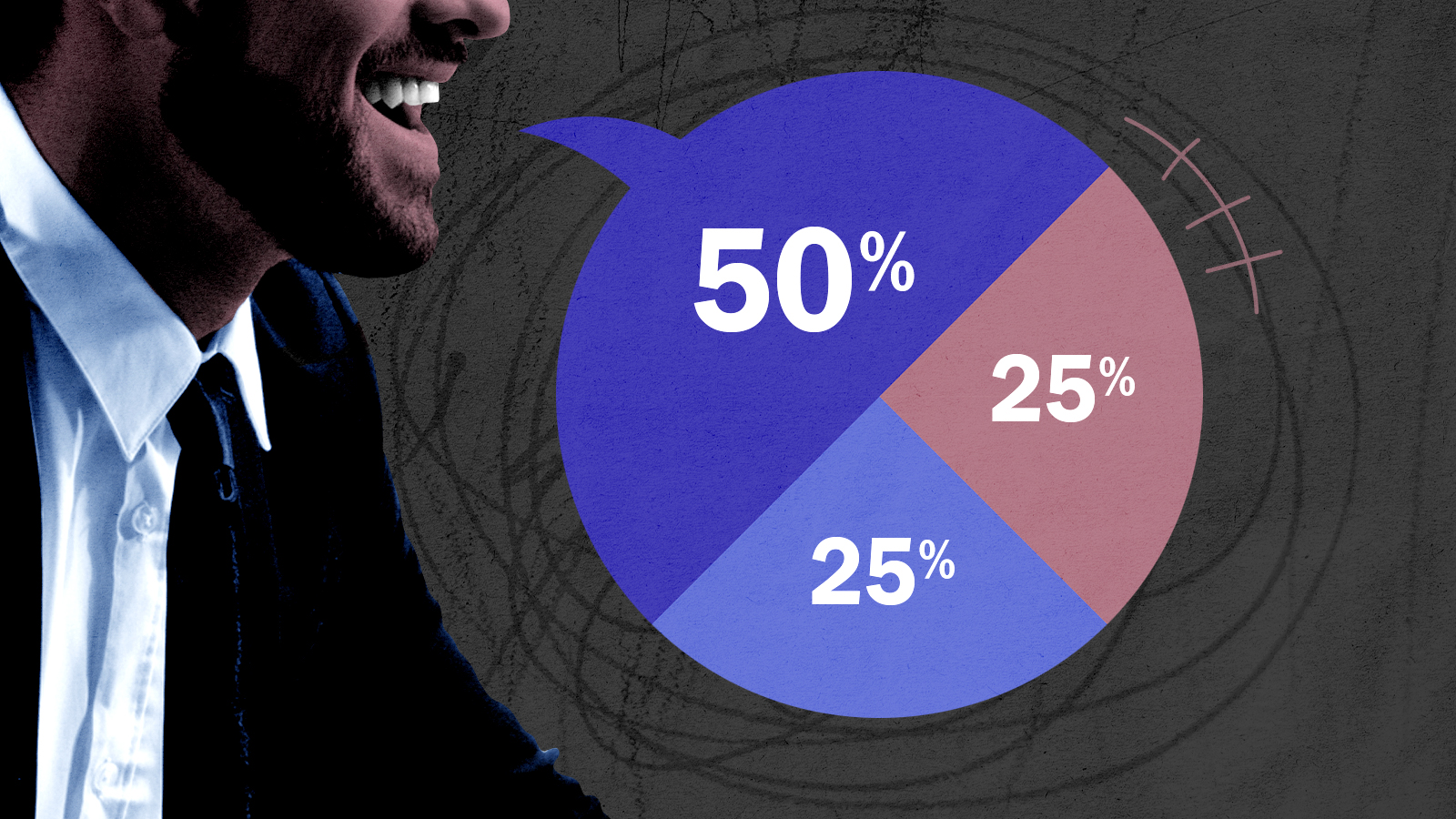

One would think that a party that currently controls the federal government would use it to stop themselves from being rigged out of power forever. But not if you only do popular things! Getting rid of or reforming the Senate filibuster doesn't get majority support. Nor does banning partisan gerrymandering on a party-line vote. And adding more justices to the Supreme Court — where a turbo-reactionary majority hews to the noble principle of "if Democrats do it, then it is unconstitutional" — is far underwater, with 26 percent support and 46 percent against. (Notably, only 43 percent of Democrats support it, probably because party elites like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi are against the idea.)

In theory, one could imagine a politician that took popular stands on policy, yet took aggressive procedural actions when it couldn't be avoided (as Shor indeed suggests). In practice this does not happen. The reason is that the neoliberal decades have produced a class of wimps: Democratic politicians who are fearful, timid, and hesitant when it comes to pursuing their own interests or confronting Republicans. They are bold and aggressive only when they are fighting internal battles with the nearly-powerless left of their own party, who threaten their cushy post-office consulting gigs.

Obsessively monitoring polls and instantly trimming down or throwing out policies that don't register a strongly positive poll result will tend to reinforce that wimpy attitude. It will also tend to rule out unpopular but tactically sound moves, like for example pushing through with an economic stimulus that may not poll well today but will ensure unemployment is low on Election Day. Conversely, Bill Clinton's passage of free trade deals may have paid off politically in the short term, but did tremendous damage to the Democrats' long-term performance in the numerous places that were harmed.

Now, to give the surveyors their due, polls certainly have their place. Their argument for a focus on concrete economic policy that will create lots of jobs is largely correct. But they are no more immune to bias than anyone else. And popularity in high places reliably indicates that one is saying what the powerful want to hear more than it does the discovery of political data wizardry.

The classic Democratic combination of timidity and seething hatred for their only energetic leaders was on full display this week as Rep. Cori Bush (D-Mo.) and a few others staged a sit-in outside the Capitol building to delay the cancellation of a pandemic eviction moratorium that could have created a politically-calamitous homelessness crisis across the country, all while much of the party establishment (along with pro-Israel lobbyists and Republican groups) pulled out all the stops to defeat Sanders protege Nina Turner in an Ohio congressional primary election. Biden, after unconvincingly hemming and hawing for a month, abruptly reinstated a watered-down version of the eviction ban, and Turner indeed lost.

But the bedrock political reality today is that the Democrats have had the consistent support of a solid majority of the country for well over a decade, while Republicans are plotting to exploit the wildly un-democratic features of our 18th-century Constitution to institute permanent minority rule. For instance, as Shor has (correctly) argued, the Supreme Court is a tyrannical, racist institution that should be radically disempowered. The same is true of the Senate. To ensure even a remotely fair election next year, much less put through reforms to these institutions, Democrats will need to muster guts and determination that are not currently in evidence.

Looking at polls more is not likely to help.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.