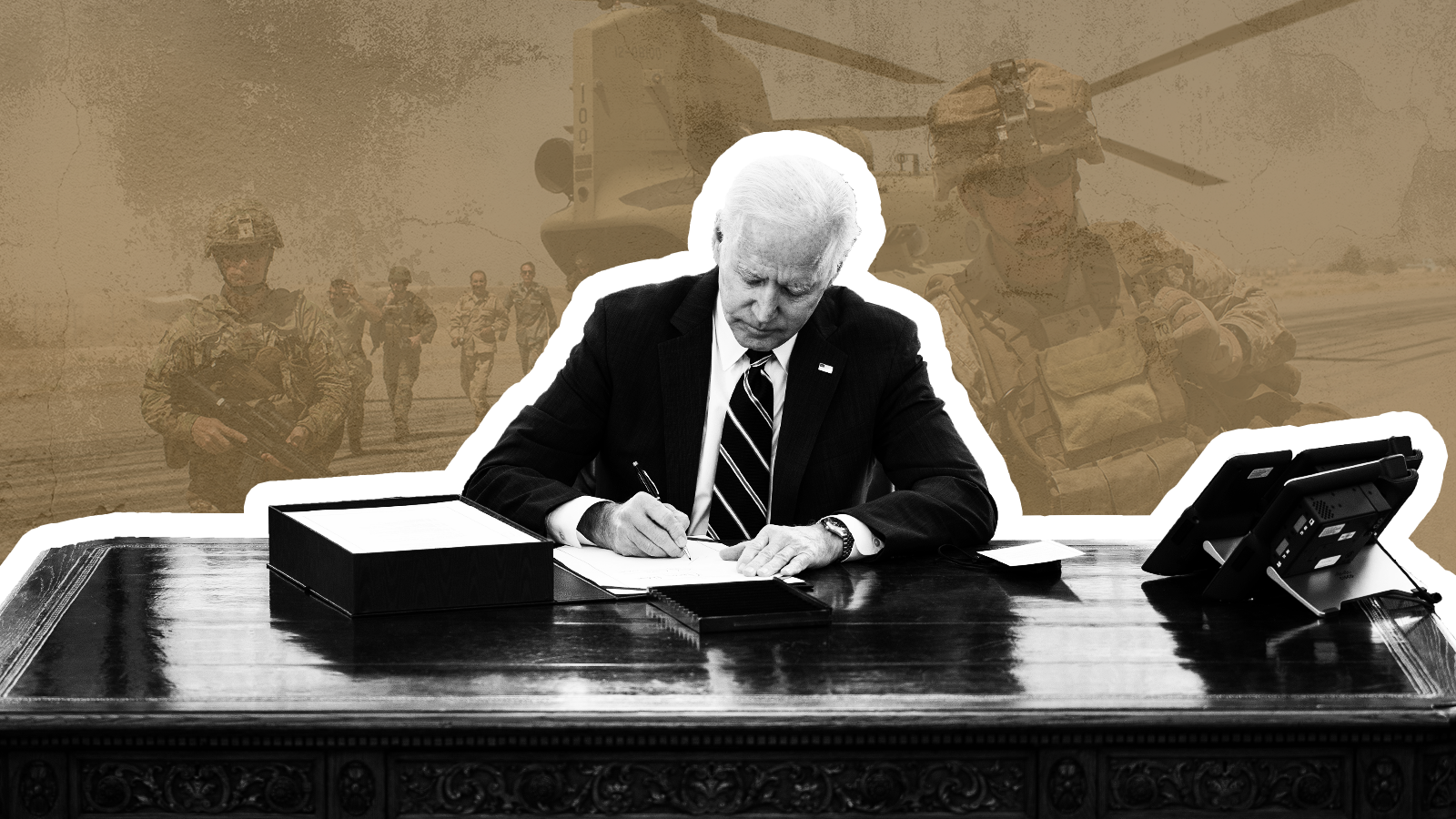

The end of America's post-9/11 delusion

A rapid collapse in Afghanistan caps off 20 years of refusing to acknowledge the limits of American power

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We must first remember how it all started. The attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 were genuinely terrifying and disruptive. But the understandable shock and emotional trauma of 9/11 sent the United States off on a series of impossible, poorly planned and incompetently executed quests. President George W. Bush, who had promised a more "humble" foreign policy in his campaign against Democrat Al Gore, launched what he called a "Global War on Terror" (GWOT) in the aftermath of the attacks. "Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there," he said on Sept. 20 before outlining the completely unachievable goal that would warp the early 21st century. "It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated."

Oh.

The rapid collapse of the painstakingly created government in Afghanistan over the weekend brought a decisive end to the post-9/11 era of military interventionism. There is plenty of debate to be had and plenty of blame to distribute about what led to such a chaotic endgame, but the bigger picture has been clear for some time. The costly, bloody project to transform Afghanistan in the wake of the 9/11 attacks failed spectacularly, and what must emerge in its aftermath is a foreign policy based on a pragmatic understanding of the limitations of American power, rather than on fundamentally delusional appraisals of its limitless extent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It should have been clear even as Bush spoke 20 years ago that the U.S. lacked the capability to eliminate "every terrorist group of global reach," but with most of American society consumed with paranoia and bent on revenge, off we galloped into the abyss. The primary method the U.S. would deploy in the service of eradicating all terrorism from the face of the Earth was military force. The halcyon glow of the Persian Gulf War, a quick and decisive expulsion of the Iraqi military from Kuwait in 1991 that exorcised the demons of the Vietnam quagmire, still burned brightly 10 years later, giving both citizens and policymakers false confidence about what could actually be achieved with bombs and bullets.

At no point did U.S. leaders try to make simple distinctions between thorny policy problems and existential threats to the integrity of the country, and between things that we would prefer to happen and things that absolutely must happen. Had they done so, they would likely have concluded that neither the Taliban nor Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq posed a significant enough threat to the United States to justify the resources in lives and treasure required to eliminate them.

They could have accepted the Taliban's offer to turn Bin Laden and his associates over to a neutral country for trial, or the multiple attempts the organization made to surrender to the United States after the war began. They could have recognized that although it would be great if Saddam Hussein's tyranny was replaced by a democracy, it was by no means necessary for the safety and security of Americans that we go in and try to do it ourselves against the wishes of the vast majority of the people who lived there.

But Bush and his inner circle weren't willing to settle for half-measures. The dead of 9/11 had to be avenged, the Taliban extinguished, Bin Laden killed, al Qaeda vaporized like the planes his henchmen flew into the Twin Towers. Allowing the Taliban to remain in power, even if they cooperated in rolling up al Qaeda, was seen not just as a suboptimal policy option, but beyond the pale of reasonable discourse. Vengeance was on the march, and when the American military was finished meting it out, we would simply build a new Afghanistan in place of the one we razed, like putting up a new McDonald's.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Just one member of Congress, Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) voted against the authorization for the use of military force in Afghanistan. In an essay published a few days after her lonely vote (the measure passed the House 420-1), she wrote, "I do not dispute the president's intent to rid the world of terrorism — but we have many means to reach that goal, and measures that spawn further acts of terror or that do not address the sources of hatred do not increase our security." Lee, alone among her esteemed colleagues, grasped the concept of blowback. Alone among her colleagues, she recognized that the wars she was being asked to authorize could not possibly achieve their lofty goals. Every other elected member of Congress, on the other hand, gave in to the grandiose and obviously hollow demands of the GWOT, a preview of two decades of handing U.S. presidents blank checks to fight wars that were lost before the troops set foot on the ground.

Lee was assailed as a traitor at the time. But the trajectory of our involvement in Afghanistan suggests she was spot on. The billions spent rebuilding Afghanistan and propping up its government did not rid the world of terrorism, but simply shifted its center of gravity elsewhere. The reckless invasion of Iraq destabilized the region and led to a flowering of new and even more brutal groups like ISIS. Our luxury class military was incapable of securing the basic sovereignty of either state, let alone create flowering Jeffersonian democracies that would transform the politics of the whole region, as Bush's hallucinatory advisers believed.

Those illusions died extremely hard, but the events of this past weekend should put to rest any lingering beliefs in American omnipotence. A country incapable of using its $700 billion military to safeguard a single airport against a ragtag band of militants is not a country with the power to destroy every terrorist group on the planet while simultaneously carrying out ambitious plans to remake distant societies whose politics, cultures, and histories we barely understand. How darkly fitting that a project launched to avenge the falling men and women of the World Trade Center ended with desperate Afghans toppling off of departing U.S. military aircraft, a scene so devastating in its indictment of our arrogance and failure that it almost felt scripted.

From the wreckage of this embarrassing and enormously consequential 20-year-long failure must emerge a new foreign policy doctrine based on American interests and not American mythology. This doctrine, what the grand strategy theorist Barry Posen calls "restraint" is based, as he argues, on the idea that "the United States is quite secure, due to its great power, its weak and agreeable neighbors, and its vast distance from most of the world's trouble, distances patrolled by the U.S. Navy." Our strategic posture should be based on some version of "offshore balancing," the idea that, as John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt argued in 2016, the U.S. should "forgo ambitious efforts to remake other societies" and concentrate on helping allies manage affairs in the regions, intervening only when strictly necessary and not wasting American power and resources indefinitely garrisoning strategically inconsequential countries or overreacting to each act of terrorism by launching unwinnable wars.

Thankfully, this is the direction the U.S. has been moving, in fits and starts, under the last three presidents. The American people have seen the terrible cost of our hubris, and at least for now, want no further part of it. It is now up to President Biden and his advisers to forge, from the ashes of this searing catastrophe, a new and sustainable foreign policy, informed by both our values and our limitations, that balances aspirations with difficult realities, that doesn't waste trillions in the service of unattainable goals and that doesn't give false hope to people whose futures we will ultimately be unable or unwilling to secure.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.