The 4 fantasies dominating American politics

Our political flights from the rigors of reality

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The two parties are as ideologically polarized as they've been within living memory — and they're also very evenly matched. Yes, Democrats win somewhat more votes on a national basis, but thanks to the distinctive character of the country's state-based electoral system, Republicans remain competititive, if not advantaged, in many races. Then there are divisions inside each party, with progressives and centrists battling each other within the Democratic Party and the GOP divided between Trumpist insurgents and deposed members of the party's old center-right establishment.

Add it all up, and we're left with a demoralizing political reality in which neither side can prevail decisively enough or stick together long enough to enact real change. Instead of confronting that fact, many have retreated into political fan fiction, in which each major faction indulges in daydreams about victories that are impossible in the world as it actually exists.

That is often bad — a flight from the rigors of reality. But in rare cases, it can also point the way to way toward a better, more hopeful future.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The progressive fantasy has been rising in volume and influence in the Democratic Party since Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) first advanced it in his potent primary challenge to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential primaries. Today it is embraced by leading members of the party, from grassroots activists and left-wing pundits to prominent members of Congress and even sometimes the lifelong moderate in the White House.

This is a fantasy of sweeping transformation — a New New Deal or Greater Society enacted despite President Biden and his party holding the narrowest of majorities in the House and Senate. Pass multiple trillions of dollars in spending and not only will the country thrive as a whole, this fantasy says, but the right-wing populist challenge to progressivism will be co-opted, with working-class voters across the country flocking to the left. Instead of building overwhelming majorities, then claiming a mandate for action, as Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson both did, such support can supposedly be conjured into existence by pre-emptive action (despite a significant portion of the Democratic Party itself wanting to do and spend considerably less).

The Trumpists have their own version of the same fantasy. They, too, want to enact sweeping change — sharply cutting regulations on business, deconstructing the administrative state, shutting down most immigration, giving the religious right real victories on social issues, and disentangling the country from encumbering alliances and treaties ("American First"). Yet, like the progressives, the Trumpists have insufficient popular support in the country or even their own party to get it done.

Trumpists like to pretend that if they could only manage to accomplish their goals, they'd be amply rewarded with the widespread, cross-ideological support they currently lack. Of course, the Trumpists also delude themselves in thinking they have a leader competent and continent enough to get it done. If former President Donald Trump's one-term tenure has taught us anything, it's that his lack of fitness for the job is total.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Then there are the fantasies of the sensible centrists who imagine responsible members of the two parties finding common ground and building an otherwise elusive policy consensus on more than infrastructure (narrowly defined). If only enough people in both parties were willing to embrace a form of pragmatism that prizes low taxes, social liberalism, broad-minded immigration reform, and a foreign policy of hawkish internationalism — and if only these positions were championed in a tone of civility by candidates of personal rectitude — then centrists could run the table, leaving populists of both parties in the dust.

As a kind of centrist myself, I share some of these hopes, but it's still a fantasy to suppose that this precise mix of policies, which generally dominated the Republican Party from 1980 to 2016 and the Democrats during the administrations of former Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, represents the political future rather than its mostly discredited past.

Finally, we come to the third-party fantasists who go one step further than the sensible centrists in proposing that those who object to trends in the two major parties bolt to form a new and independent political institution. Given the long track record of third parties serving mainly as spoilers in this country — a pattern near-inevitable in America's electoral system — it's hard to see this as anything other than the most delusional fantasy of all. Third-party candidates can sometimes win in House districts. They can occasionally prevail at the state level. But it is exceedingly unlikely that the member of such a party could come anywhere close to winning substantial power in Congress, let alone the presidency.

None of these options are rooted in reality, but they're appealing to many people because our polarized, partisan war of attrition is so exhausting and feels so futile. The possibility of great collective accomplishment feels far out of reach.

Politics needs people with their feet firmly planted on the ground — people who know how to avoid making foolish mistakes that can set political causes back even further. But this recourse to political fantasy isn't all bad. What is it that sometimes sets history off in new political directions if not dreams of alternative futures with few antecedents in the world as it is? Sometimes an intellectual, pundit, or politician proposes an idea or ideal that "creates a public" in support of a new agenda or vision of the future, and as a result opens up new possibilities for electoral majorities.

I don't see any such majority emerging from the prevailing political fantasies of the moment. But I could be wrong. It could also be that the next fantasy to emerge is the one that finally wins widespread popular support, breaks us out of our interminable stalemate, and expands the bounds of political possibility.

Political fatalism can generate its own antidote. That's something to keep in mind the next time you find yourself rolling your eyes at the seemingly fantastical indulgences of political opponents. They just might be giving birth to a more hopeful political future.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

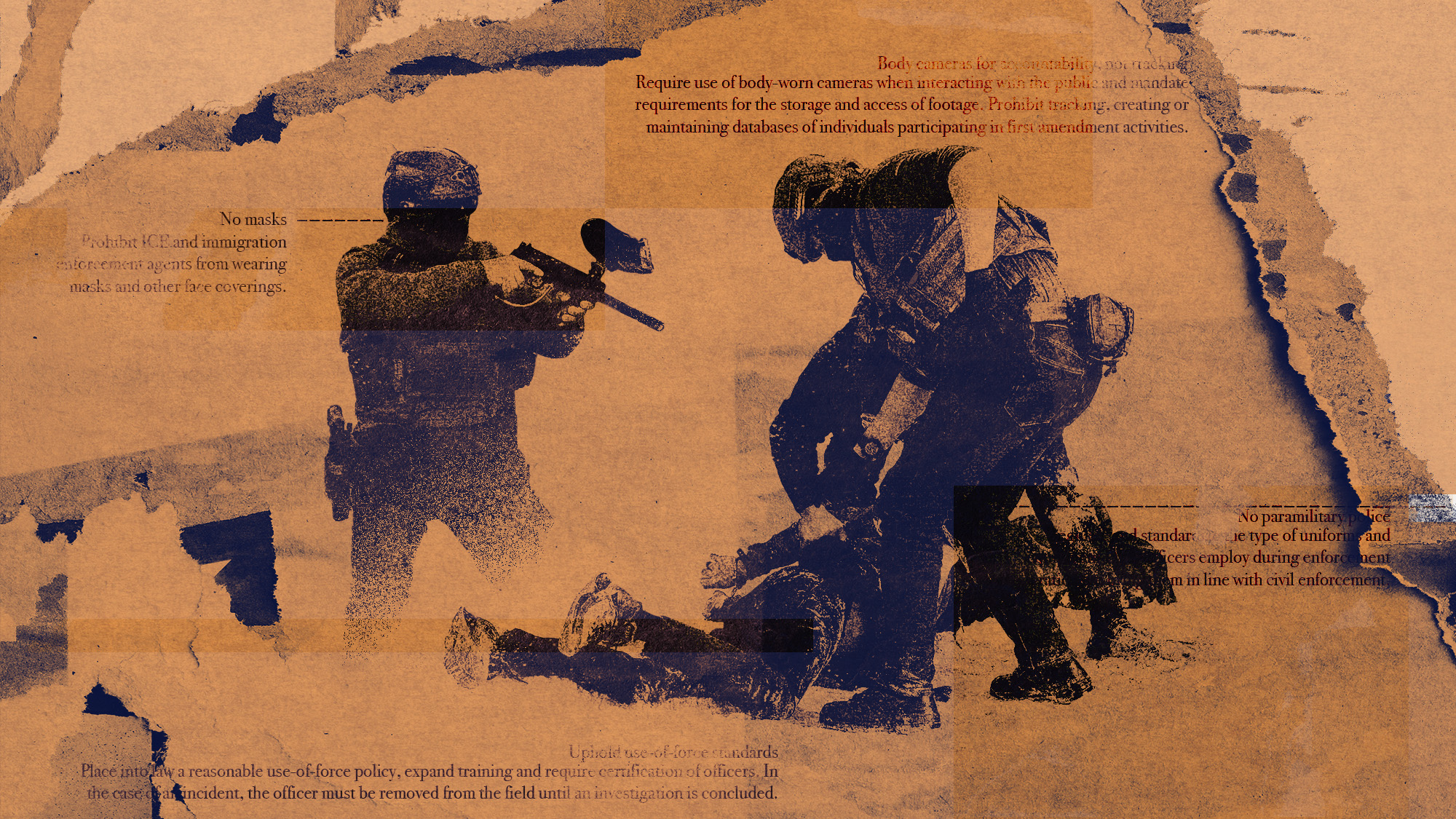

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned