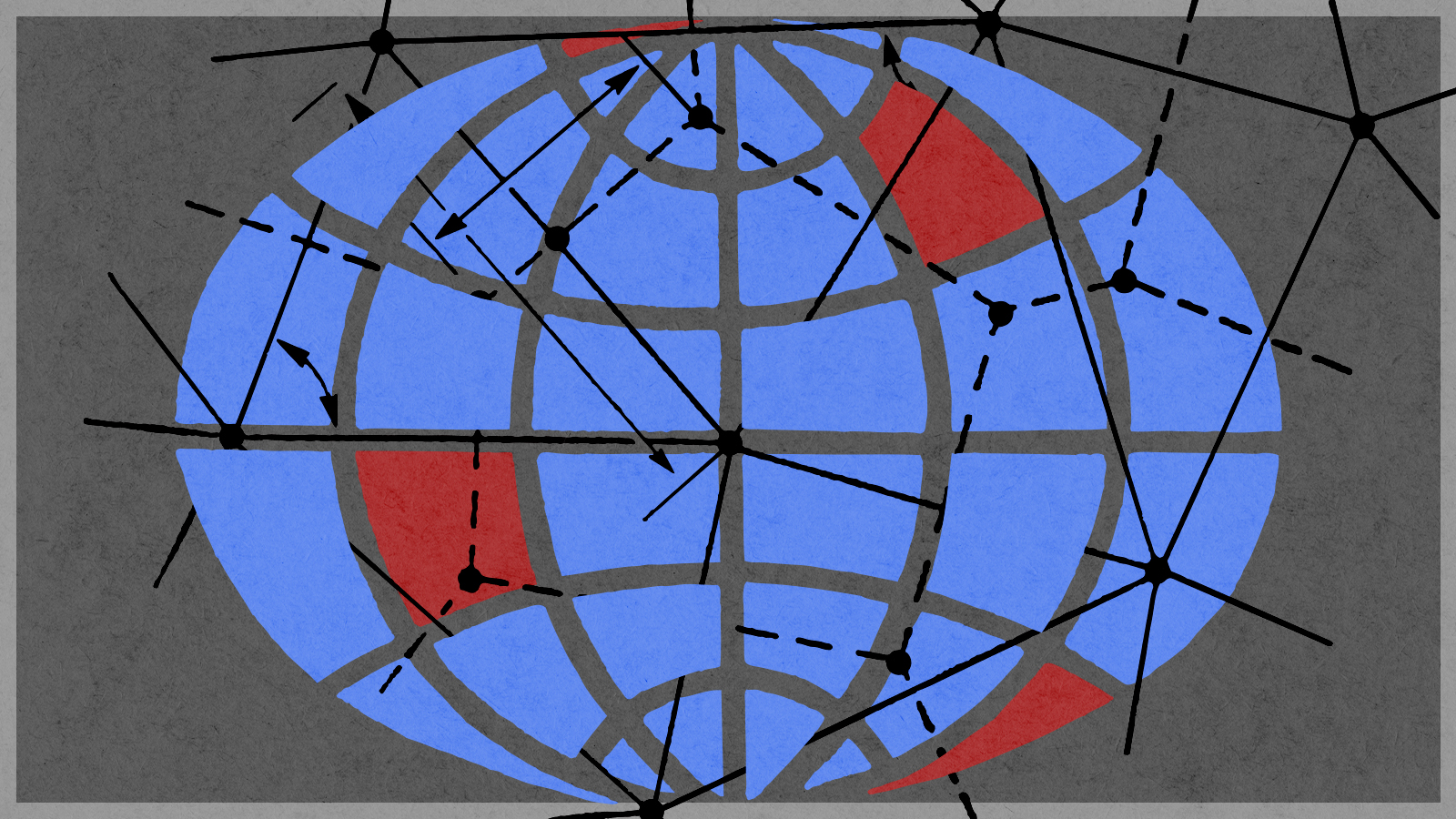

The liberal world order is gone, but the West lives on

Universal values now get only spotty coverage around the globe

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The invasion of Ukraine is only in its third week and far from resolution. But it's already launched thousands of essays, podcasts, and tweets. While the inhabitants of Mariupol, Kyiv, and other cities face bombardment, writers and scholars in the peaceful capitals of North America and Europe lob words at each other. As we try to figure out what it all means, it's important to remember the difference between intellectual if not always civil disagreement and the reality of war and enmity.

In the spirit of honesty, I should acknowledge that some of those salvos were mine. The day after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the commencement of operations, I published a column proclaiming the end of the so-called liberal international order (or its common synonyms). That argument provoked a critical response from my colleague David Faris. Noting the coordination and severity of American, European, and NATO responses, Faris contended that the basic premise of the post-Cold War politics — that interstate aggression is wrong and must be punished — remains in place.

It's fair to conclude that reports of liberalism's death have turned out to be premature. The Stanford historian Stephen Kotkin and other scholars have argued that the last few weeks have exposed the gap between Russian aspirations and capabilities. Even if Russia defeats Ukrainian forces in the field, that lesson may infuence other states that hope to dominate hostile territory. Although the available reports are hard to assess, it appears that the Chinese Communist Party is worried about the implications of Russia's unanticipated political and military struggles for its own efforts to capture Taiwan.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But there's also a sense in which eulogists for the liberal world order and optimists about its prospects can both be partly right. One of the notable features of international opposition to Russian is how limited it is. China's not the only player to opt out of sanctions. India, Brazil, and (until recently) even Israel, have objected to aspects of the campaign to isolate Russia.

Rather than an assertion of global liberalism, we may be seeing the return of a concept that's become unfashionable over the last few decades. In an underappreciated recent book, historian Michael Kimmage shows how "the West" became a central concept in American foreign policy for much of the 20th century before falling into disrepute. The whole point of the "new world order" announced by President George H.W. Bush in 1990 was that liberal practices and ideals would no longer be associated with one culture or region. Instead, they would become truly global norms and universal rights, administered partly, if not entirely, by transnational institutions.

That's the expectation, perhaps utopian, the Russian invasion and varied responses around the world seems to refute. Some states — mostly, if not exclusively those linked to the Western alliance of the 20th century — reject Russian aggression and the vision of great power competition that inspires it. But others, including population and economic giants, are either morally indifferent or give precedence to other interests.

Yet the popularity and sometimes irrational intensity of opposition to Russia in the "Anglosphere" and Europe suggests a residual solidarity that belies the revival of illiberal nationalism within those regions. As William Galston observed in The Wall Street Journal, Western admirers of Putin including Italy's Matteo Salvini, France's Eric Zemmour, and our Donald Trump have all had to distance themselves from the Russian dictator in the face of overwhelming criticism — even from their own supporters. Ordinary Americans and Europeans with populist sympathies, who were far from philosophical liberals before the invasion, haven't turned into Kantians overnight, and it's naive to imagine they ever will. But many hold assumptions about the purposes of violence and requirements of political legitimacy that are implicit in liberal societies and questionable or even alien outside them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In more abstract terms, then, we may be witnessing an emerging synthesis between two rival theories that captivated political intellectuals in the beginning of the period of hegemonic liberalism that now seems to be in its twilight. One was the "end of history" thesis developed by Francis Fukuyama. Contrary to popular misinterpretations, Fukuyama did not claim that the resolution of the Cold War meant nothing unpleasant, difficult, or surprising would ever happen again. What he did argue was that there were no longer systematic alternatives to liberal democracy capable of achieving broad popular support.

Fukuyama was challenged by his former teacher Samuel Huntington. According to Huntington, the future would not be characterized by consensus around liberal institutions and human rights, but rivalry between distinct cultural groups. That rivalry was likely to turn violent at "bloody borders" at the overlapping periphery of those civilizations — that is, places like Eastern Europe.

But what if they're both right? In other words, what if the West really has reached the end of history but other parts of the world are following a different script? That would involve closer ties, even homogenization, among liberal states — bad news for advocates of sharply differentiated national identities. At the same time, the influence of that quasi-integrated bloc over the rest of the world might diminish as rivals develop their own cultural, economic, and military resources, contrary to liberal hopes. That could lead to new and different conflicts in the future, increasing strife while belying neat distinctions between democracies and autocracies. To different degrees, India and China both support Russia. But they don't exactly get along with each other.

Writing in The New York Times, journalist Thomas Meaney recently considered the limitations and risks of this scenario. He noted that the boundaries of the West are, at best, fuzzy (I made a partial attempt at definition here); that the concept tends to subordinate Europe to the United States; and that appeals to civilizational differences can exacerbate conflict and justify atrocities. In themselves, all these criticisms are fair enough. But the fact that countries including Indonesia, Nigeria, Brazil, India, and of course China have been so skeptical of American and Europeans efforts to constrain Russia underscores the continuing relevance of the idea of the West rather than demonstrating the availability of some alternative form of truly cosmopolitan affinity. History may not be over, but the West is likely to stick around for a while.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

‘Every argument has a rational, emotional and rhetorical component’

‘Every argument has a rational, emotional and rhetorical component’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration