Why the Ukraine crisis is being treated differently than Yemen or Syria

Liberal internationalism gets its wake-up call

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

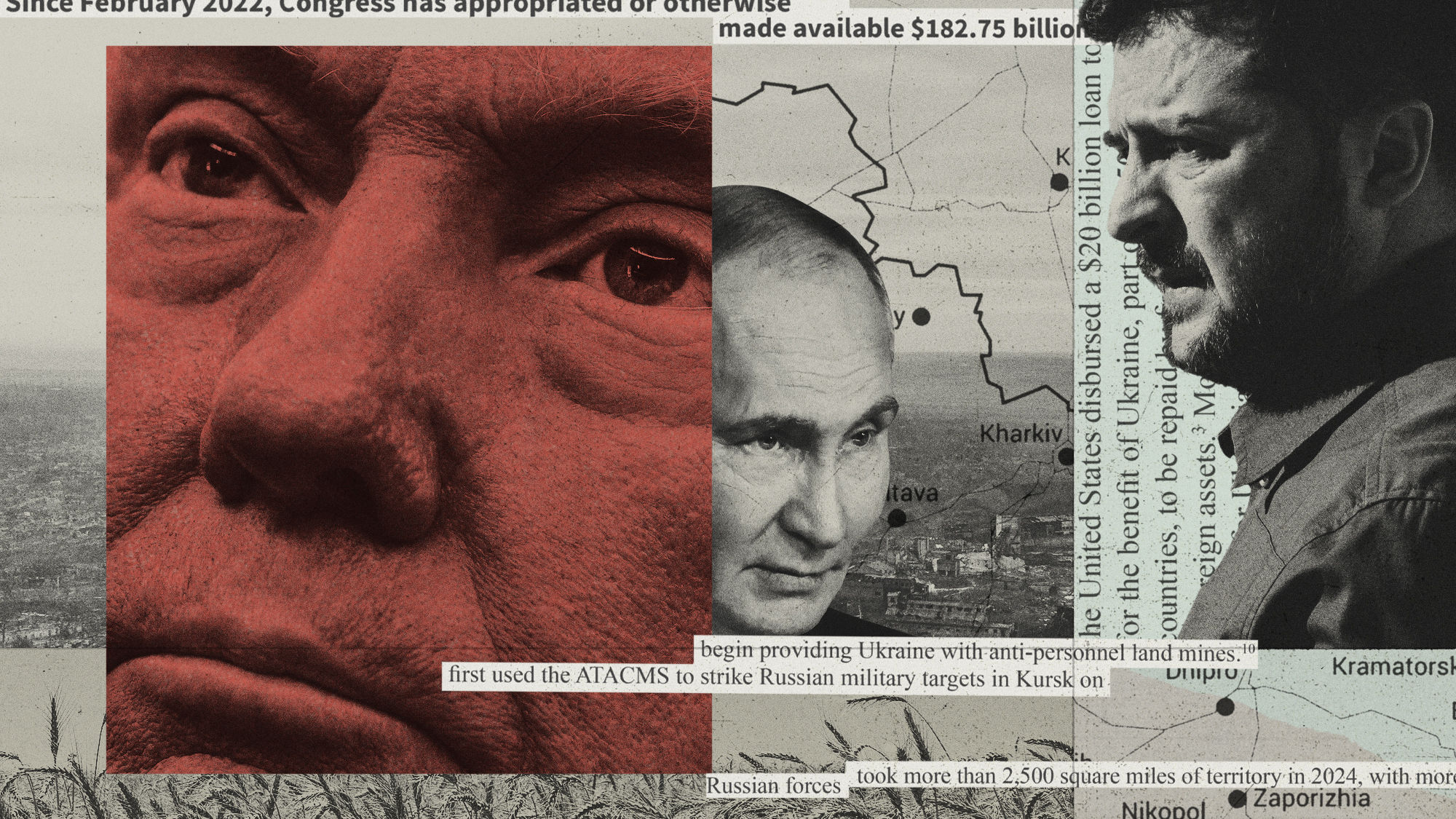

One of the many things that Russian President Vladimir Putin did not expect when he launched his gratuitously stupid invasion of Ukraine was international resolve. After all, from the genocide against Uyghurs in China to the devastating civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the international community has proven unwilling or unable to consistently come to the aid of innocent civilians facing violence and displacement.

But in having his forces beeline for the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv last week, Putin stumbled headlong into one principle that global leaders appear willing to fight for: state sovereignty.

The reaction to Russia's aggression has been swift and overwhelming. The U.S. and its allies moved to cut Russia out of the international banking system and freeze critical assets overseas. European countries closed their airspace to Russian traffic and fell over one another in the rush to provide both lethal and non-lethal aid to Ukraine — including Finland, which had maintained its alliance neutrality for decades. Germany announced a major increase in defense spending, and NATO moved to reposition forces in Eastern Europe, both as a show of solidarity with Ukraine and as a warning in the highly unlikely event that Putin is tempted to continue West.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Despite the creeping authoritarianism on the American right, supermajorities of the American people expressed disapproval of Russia's actions, proving that not every issue can be immediately polarized along partisan lines by the Fox News propaganda machine. The gallantry of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who was offered evacuation by the United States but decided to stay with his people in Kyiv, has surely played a role in galvanizing Ukrainian resistance as well as international support. At this point, there is no way that Putin will not end up paying far more than he will gain with this ill-advised provocation, including possibly his hold on power in Russia.

But it is clear what principle is driving this across-the-board pushback, and that is the right of states to be secure within their own borders. What is happening to the Ukrainian people today, while tragic and harrowing, is not experientially different than what Syrians and Yemenis have endured in recent years, or what is transpiring in Ethiopia today. While outside actors may be involved in these conflicts, they are civil wars, and the external patrons of various factions do not have designs on permanent occupation or annexation of territory.

My colleague Samuel Goldman wrote that the Russian invasion of Ukraine heralds "a decisive end to the era" of rules-based internationalism. If it leads to a period of widespread and successful territorial land-grabs and interstate wars launched by revisionist powers, he might be right. But there's another way of looking at it. The liberal international order, after all, was never capable of preventing territorial aggression altogether. But since the Second World War, there has been a consensus that this aggression is wrong. Whether force or even economic statecraft was used to roll back territorial gains always depended on the relative balance of power between norm-enforcers and aggressors.

What hasn't really changed is the normative principle that interstate war should not happen. The U.S. felt the wrath of global condemnation with its outrageous and self-defeating invasion of Iraq in 2003 just as the Soviet Union did in 1968 when Leonid Brezhnev ordered the invasion of Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring reform movement. That neither was meaningfully punished for their actions says less about the global acceptance of the principle of state sovereignty and more about the overwhelming power asymmetries that allow the strongest states to violate international law.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What would herald the true end of the liberal international order would be global indifference to interstate aggression. And that's not what we see here. On the contrary, Putin's reckless invasion and barbaric siege of major Ukrainian cities have created a global sense of indignity, forcing even governments that are very reluctant to tussle with Moscow to get off the fence. Only the cold reality of Russia's nuclear arsenal is preventing NATO from intervening to rescue Ukrainian democracy, but other punitive measures are being thrown against the wall to make the costs to Russia as steep as possible.

Ironically, the sanctity of sovereignty has long been a cherished principle for Russia. After all, it was Putin himself who declared in 2008 that the NATO-led creation of an independent Kosovo carved out of Serbia "will de facto blow apart the whole system of international relations, developed not over decades, but over centuries." He then added ominously, "At the end of the day it is a two-ended stick and the second end will come back and hit them in the face." Later that year, Russia went to war with Georgia, a development that would mark the beginning of a new phase of Russian expansionism.

Putin calculated that because he paid no major price for annexing Crimea in 2014, the global community neither cared much about Ukraine nor would do much of anything to oppose Russian efforts to claw back territory from non-NATO states on Moscow's periphery. But it seems more likely that world leaders mistakenly believed he would stop there. The move from piecemeal dismemberment of Ukraine to total obliteration triggered a normative tripwire that finally alerted the democratic world to the gathering menace of Russian revanchism and the broader phenomenon of authoritarianism on the march.

But Putin clearly misjudged the international community's commitment to sovereignty as a going concern. It is one thing to implicitly accept that there is insufficient resolve to intervene in every civil conflict that erupts around the world; it is quite another to stand aside and watch one U.N. member state get gobbled up by another without even the flimsiest pretext.

Giving real teeth to the principle of sovereignty was perhaps the most important piece of the effort to prevent another calamitous world war driven by the imperial ambitions of expansionist countries. And while effectively freezing borders has led to a great deal of subnational conflict, it has largely succeeded in making it more or less unthinkable for a state to embark on a campaign of subjugating neighbors by force as part of a project of regional or continental domination.

Whether the punitive measures that have been put into place will succeed in restoring Ukraine's democracy and frontiers is an open question. But the imposition of harsh sanctions and other restrictions on a country as powerful as Russia, even with the potential for significant economic blowback, is actually a sign that liberal internationalism is far from dead. In fact, this might be a wake-up call for prosperous democracies: If the long post-war peace is not to be seen as a historical aberration, it must be fought for rather than taken for granted.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

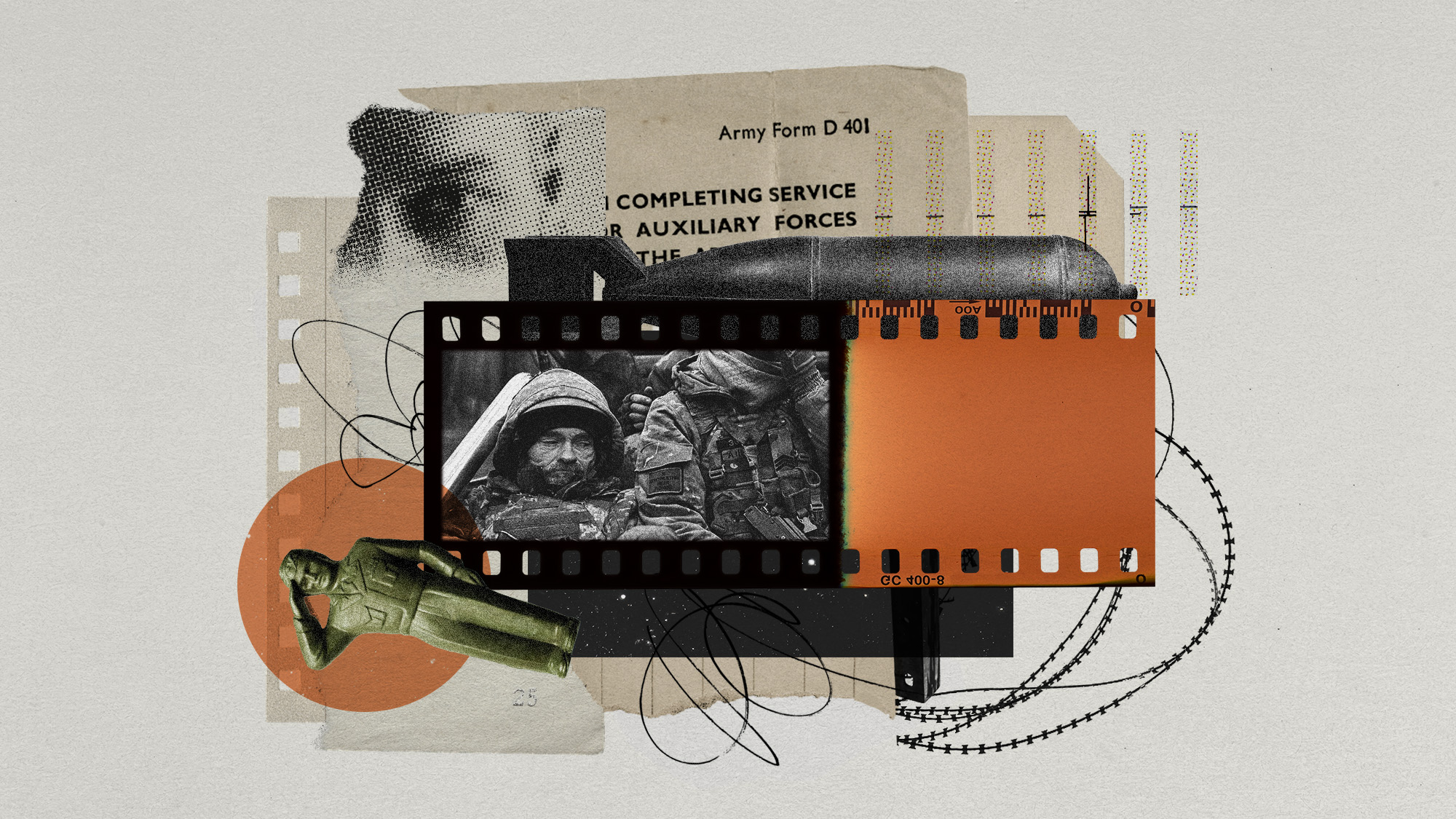

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

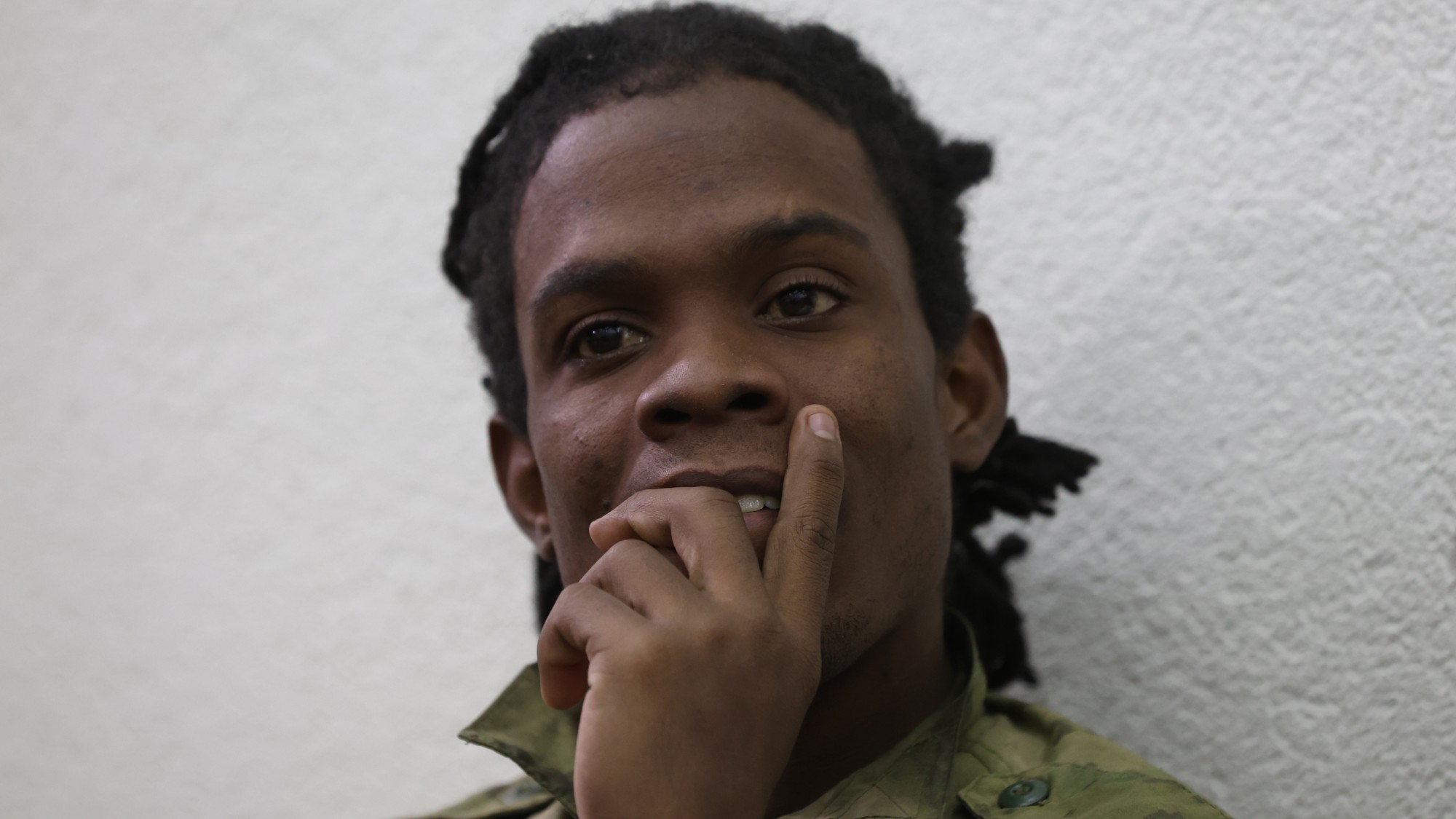

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles