Pinochet’s coup in Chile 50 years on

Half a century on, the former leader still sharply divides opinion in his home country

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is 50 years since General Pinochet seized power in Chile, ushering in more than 16 years of military dictatorship.

The Week takes a look at the events of the coup and Pinochet's long-lasting legacy in the South American nation.

What was the backdrop to the coup?

In November 1970, Chile, which had enjoyed stable civilian government since 1932, elected Salvador Allende to the presidency as the candidate of the Popular Unity coalition. Allende was a socialist, a Marxist and an ally of Fidel Castro, but also a committed democrat. Having narrowly won a three-way race (with over 36% of the vote), he implemented a radical programme, hiking public-sector wages and nationalising large farms and scores of companies, including US-owned copper mines. His actions set Chile sharply at odds with Washington. The economy contracted, inflation rose sharply and food shortages followed. By summer 1973, strikes, protests and violent clashes between left- and right-wingers were paralysing the country. A military coup attempt in June failed, but in August, the supportive "constitutionalist" commander-in-chief of the armed forces, General Carlos Prats, was replaced by General Augusto Pinochet.

How did the coup begin?

Nineteen days later, in the early hours of 11 September 1973, military units stationed throughout Chile were deployed to wrest control of urban centres, cutting phone lines to stop reports of the coup spreading. When Allende got wind of efforts to capture the port city of Valparaíso, he headed to the presidential palace, La Moneda, in Santiago. Within hours, most other independent stations had been shut off, but at 9:10am, Allende made a final, defiant broadcast to the nation in which he said he was ready to die rather than surrender to the military. "Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers! These are my last words."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did Pinochet take power?

By mid-morning, La Moneda was surrounded by tanks, and Allende was under siege. Tanks patrolled the surrounding streets, and soldiers took hundreds of civilian prisoners. At 11:55am, two Hawker Hunter jets launched 18 rockets at the palace. Dressed in a tweed jacket and armed with a gun, Allende ordered his allies to surrender at about 1:30pm; and less than half-an-hour later, he was dead (by suicide, a 2011 autopsy would confirm). Pinochet soon pushed aside the other members of the military junta and established a brutal personal dictatorship. Several rival generals died in mysterious circumstances, and Pinochet used his secret police as an instrument of state terror. The coup marked the beginning of almost 17 years of ultra-right-wing rule by Pinochet, during which he ruthlessly suppressed dissent.

How did he impose his rule?

Independent media outlets were shut down, and books by Marxist authors were burned, as part of Pinochet's efforts to banish socialism from Chile. Opponents, meanwhile, faced astonishing brutality: many were rounded up in Santiago's national stadium and other makeshift detention centres. Up to 40,000 people were tortured and more than 2,200 were executed. Pinochet's helicopter-borne "Caravan of Death", a military death squad, was sent to remote parts of the country to hunt down opposition activists. Almost 1,500 people were "disappeared": the bodies of many, it later emerged, had been thrown into the Pacific Ocean from helicopters, their stomachs slit open so that they'd sink. Pinochet also hunted down opponents abroad: in 1976, Allende's former foreign secretary Orlando Letelier was killed by a car bomb in Washington DC, along with his American secretary Ronni Moffitt. Yet for all that, Pinochet continued to command significant support both at home and abroad.

Why was he supported?

Many foreign leaders saw him as a check on the spread of communism, and many Chileans felt that he had restored order and, in time, prosperity to the country. Inflation, which had reached Weimar levels under Allende, was soon reduced. Pinochet hired the "Chicago Boys", a group of young Chilean economists who'd trained in the US under the free market champion Milton Friedman. They slashed public spending, and opened up Chile's economy, tearing down tariff barriers and privatising almost everything bar the copper industry. This radical neoliberal "shock therapy" wasn't altogether successful, and the economy crashed in the early 1980s (Pinochet, like many dictators, was also personally corrupt, amassing millions in foreign bank accounts). But Chile rebounded as the decade progressed, and Pinochet's rule impressed the likes of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who dropped an arms embargo on the regime, selling it jet fighters and training its troops.

How did Pinochet's regime end?

Pinochet was unusual among dictators in that he relinquished power voluntarily – if reluctantly – in 1990, two years after he had lost a referendum on his rule. Democracy was restored; but he remained head of the armed forces until March 1998. In October that year, he was arrested in London (where he had travelled to undergo health treatment) under an international warrant for human rights violations. He was eventually allowed to fly home in March 2000, having been deemed too old to stand trial. He died in Chile in 2006, aged 91, and was never convicted of any crimes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How is the coup viewed today?

In recent decades, Chile has been one of South America's most politically and economically stable states. But 50 years on, the coup still sharply divides opinion. A poll by Mori in March found that 42% of Chileans surveyed thought it had destroyed democracy; but 36% thought it had freed Chile from Marxism. Both Pinochet and Allende remain powerful symbolic figures. Chile's current left-wing president, Gabriel Boric, paused en route to his inauguration in 2022 to pay homage at a statue of Allende outside La Moneda. José Antonio Kast, the far-right politician who lost a close race with Boric in the 2021 election, has explicitly defended Pinochet's legacy.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

‘Melania’: A film about nothing

‘Melania’: A film about nothingFeature Not telling all

-

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrum

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrumFeature His desire for Greenland has seemingly faded away

-

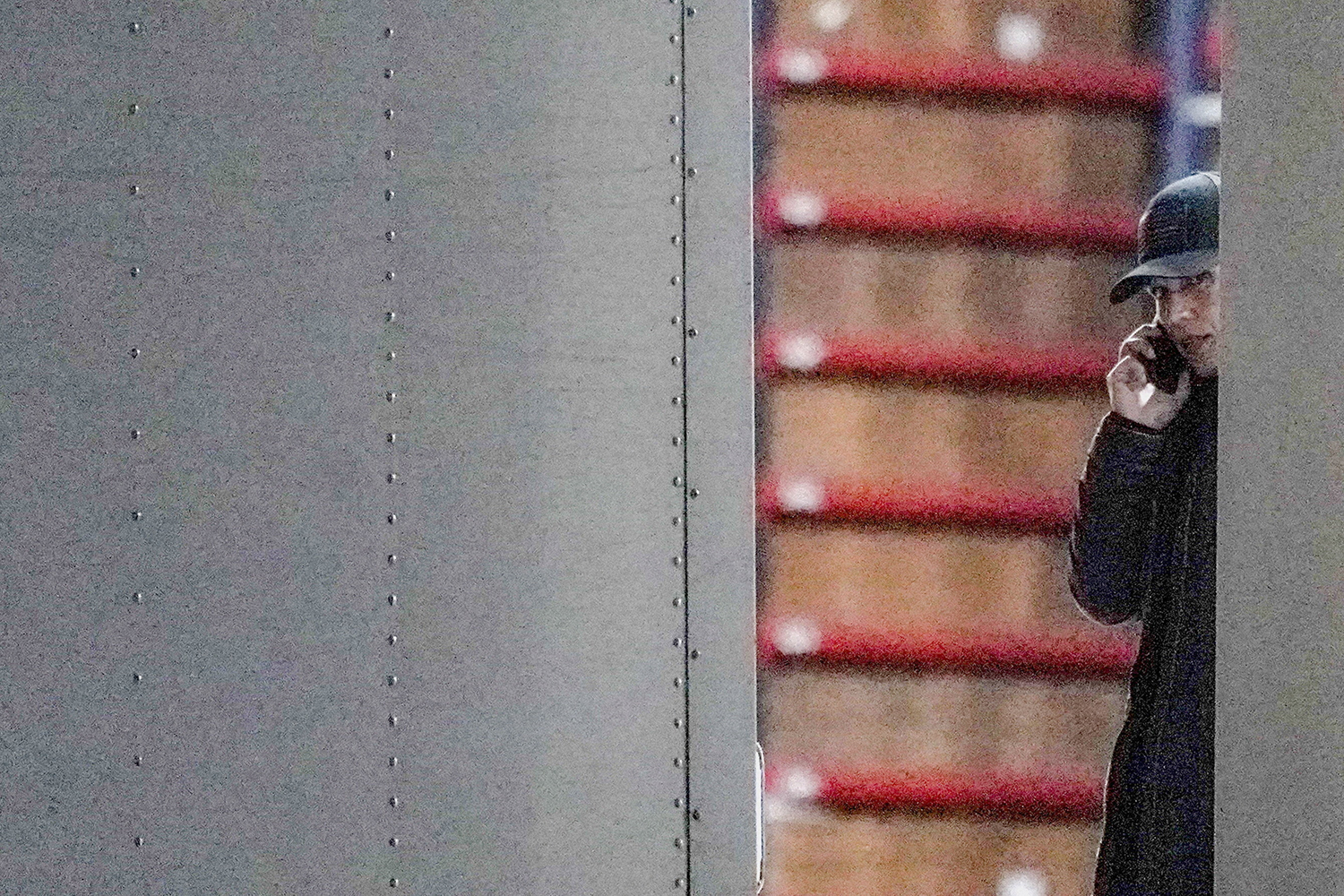

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photo

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photoFeature An image of Liam Conejo Ramos being detained lit up social media

-

The price of forgiveness

The price of forgivenessFeature Trump’s unprecedented use of pardons has turned clemency into a big business.

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’