America can't afford to be careless in the war of words against Russia

Communicating with Russia is already difficult. The president made it worse.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Western world has a Goldilocks problem in Ukraine: It wants to support that country's defense against Russia's invasion, and to do it just the right amount. Too little help and Ukrainians might be left at Russian President Vladimir Putin's mercy; too much and there's the risk of provoking a wider war in Europe. It's tough to find the right balance, and the results can sometimes look absurd — why do NATO countries feel comfortable providing Ukraine with anti-aircraft missiles, but not actual aircraft?

There's a similar challenge with wartime rhetoric. It's important for the United States and its allies to condemn Russia's aggression, but to do so in carefully calibrated terms.

On Saturday, though, President Biden wasn't so careful.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At the end of a 27-minute speech in Poland, during which he vowed both to provide a refuge to Ukrainians fleeing war and that American troops won't be sent to fight in the war, Biden took aim at Putin with an ad-libbed, unscripted remark. "For God's sake," Biden said, "this man cannot remain in power."

Oops.

If Biden meant what he said, his words were a sudden, surprise announcement that the United States is seeking regime change in Russia. The United Kingdom quickly distanced itself from the president's remarks. French President Emmanuel Macron was even more stern. And White House officials rushed to try to assure the world that Biden didn't mean what he said. "As you know, and as you have heard us say repeatedly, we do not have a strategy of regime change in Russia or anywhere else, for that matter," Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said Sunday morning in Jerusalem.

The reason for the hurried walkback of Biden's comments was clear: It will be more difficult to end the war if Putin thinks that America and its allies are out to bring him down. "There ought to be two priorities right now: ending the war on terms Ukraine can accept, and discouraging any escalation by Putin," said Richard Haas of the Council on Foreign Relations. "And this comment was inconsistent with both of those goals."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The dustup over Biden's speech reflected the broader conundrum: How to talk about the war in Ukraine? The United States and its allies want to make it clear they're not looking to start World War III, but they also don't want to accidentally invite more aggression from Putin.

There's not an easy answer. Before Saturday, some NATO officials were saying that America has gone too far in letting the world — and Russia — know that it doesn't want to fight.

"I don't think this is very productive when we say every so often, 'We don't want World War III,' or 'We don't want conflict with Russia,'" an Estonian official told the Washington Post last week. "That's a green light to the Russians that we're afraid of them."

There's certainly a case for "strategic ambiguity," the approach the United States takes toward China regarding Taiwan. America doesn't have an explicit, formal pledge to come to Taiwan's defense if China invades, but it doesn't discount the possibility either. The idea is that China doesn't really know one way or the other, and has to account for the possibility the United States might get involved in any conflict. Ambiguity thus serves as a form of deterrence that doesn't directly provoke China. (Biden, for what it's worth, has stumbled here as well.) Some observers want America to take a similar posture with Russia.

But it isn't clear that being vague is useful once the shooting has actually started, or that it serves to deescalate an already-violent situation. And it's not like the United States and Russia are currently plagued by an excess of communication: Russia's military leaders are no longer taking phone calls from their American counterparts. That's a problem. It makes it more likely that the two countries could stumble into war stupidly, based on guesses, half-truths and speculation. "When there's no communication at that level, their worst-case assumptions, often based on poor information, are more likely to drive their behavior," Rand Corporation's Sam Charap told the Post.

That means it is all the more important that the United States and its allies loudly and clearly communicate their intentions in public. Shout it from the rooftops: We don't want a shooting war with Russia! The West should be communicating clearly — and mean what it communicates. That was true before Biden's gaffe on Saturday. It's probably even more true now.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

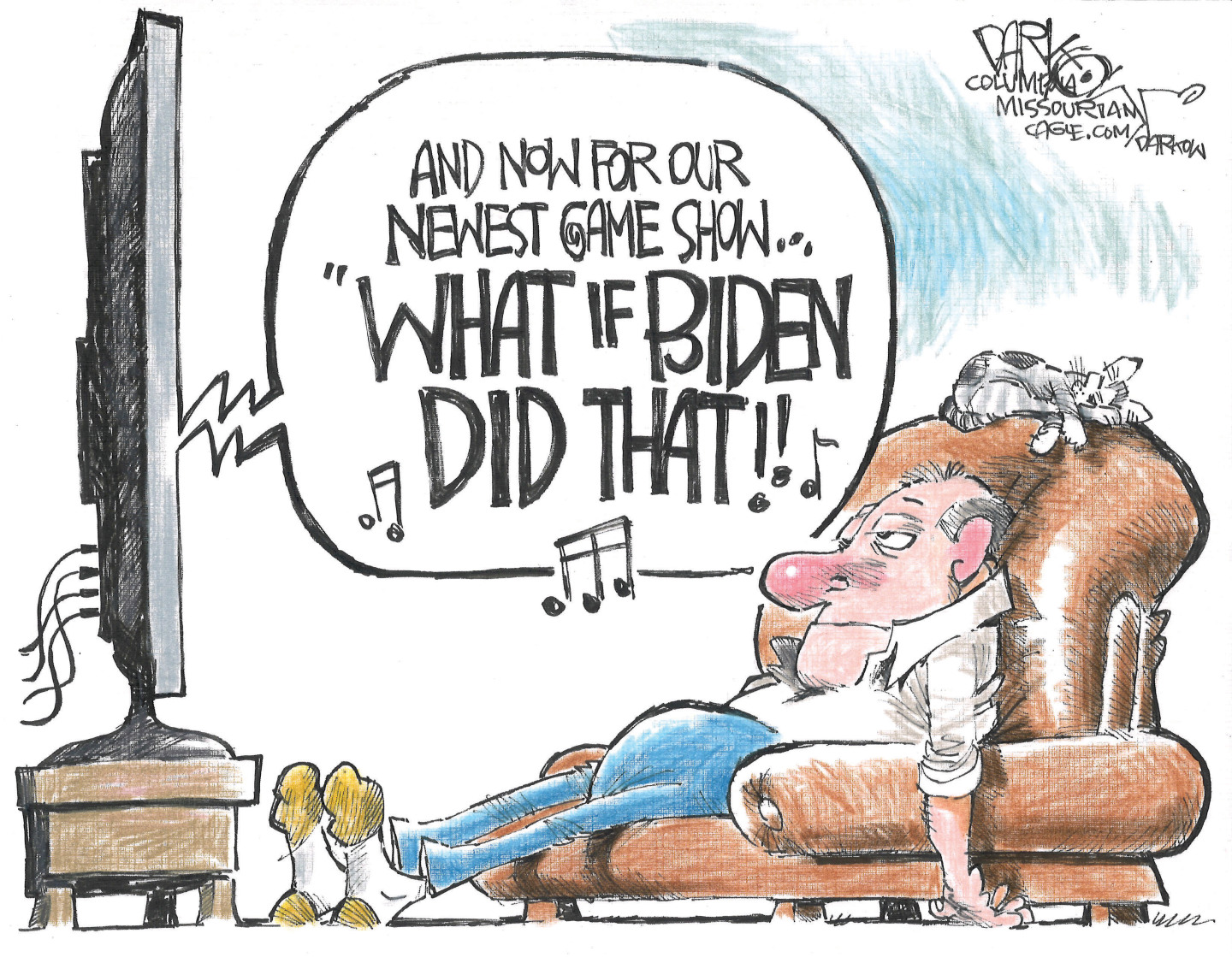

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

Palantir's growing influence in the British state

Palantir's growing influence in the British stateThe Explainer Despite winning a £240m MoD contract, the tech company’s links to Peter Mandelson and the UK’s over-reliance on US tech have caused widespread concern

-

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 February

Quiz of The Week: 7 – 13 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

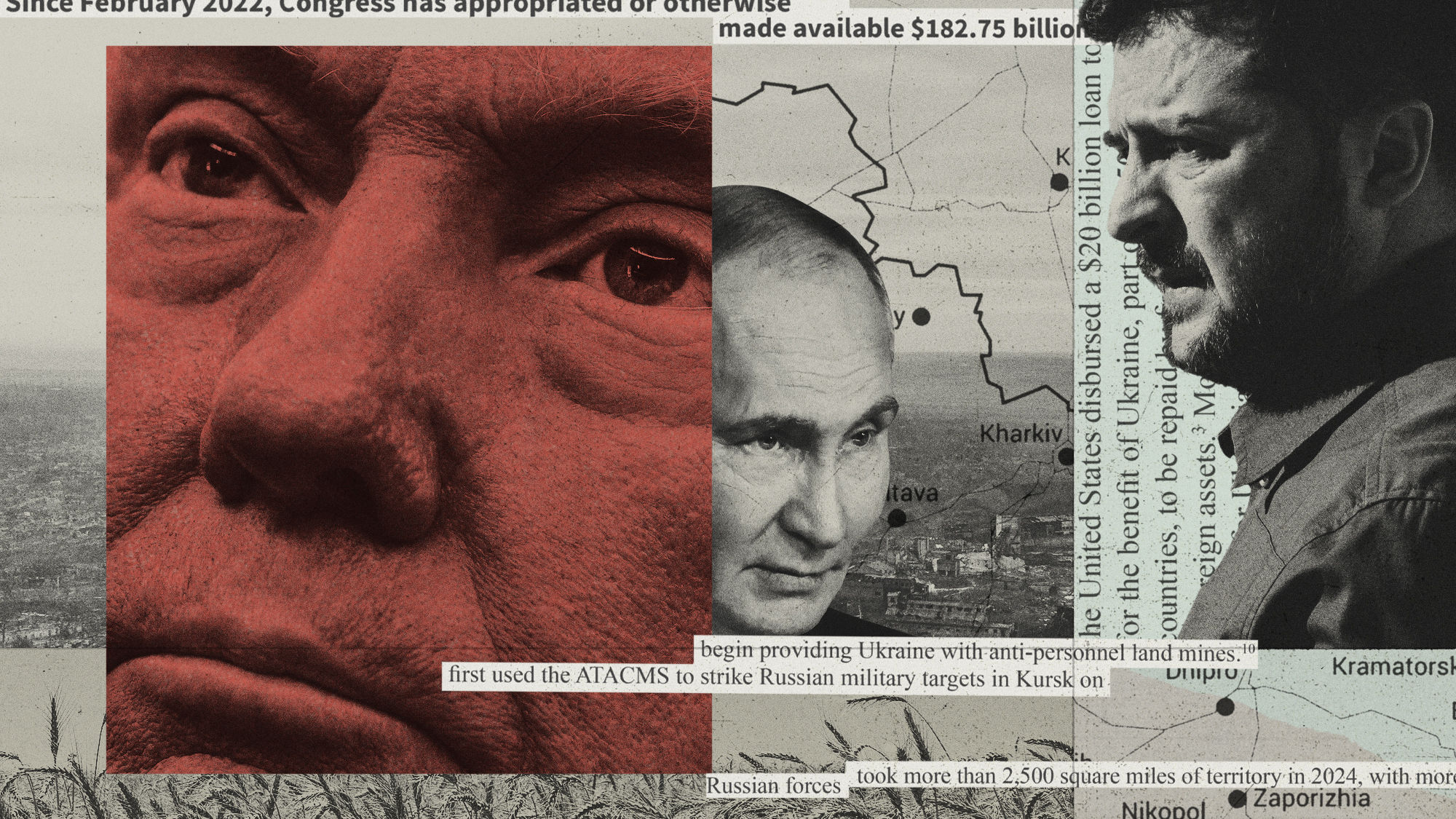

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

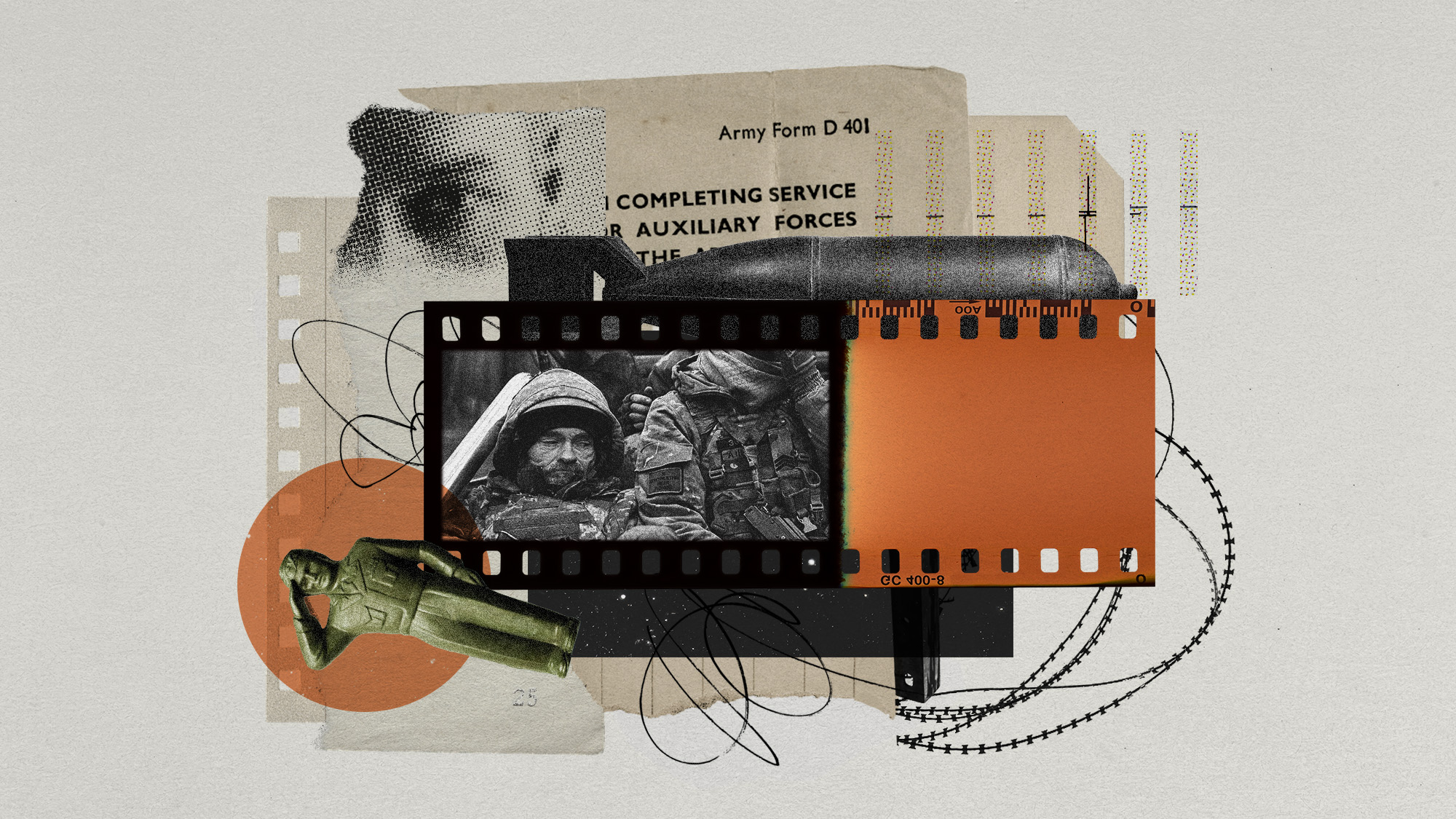

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles