What Ukraine can and can't accomplish with Western artillery

Ukraine has been outgunned throughout Russia's invasion — but it's sure putting up a fight

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ukraine has been destroying Russian ammunition depots and command centers with advanced artillery systems supplied by the U.S. and other Western nations. The arrival of U.S.-supplied High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) has allowed Ukrainian forces to keep Russian invaders at bay in eastern Donetsk province and to partially isolate Russian forces in southern Kherson as Kyiv broadcasts its intention to retake the area in a counteroffensive.

But Ukraine's HIMARS alone won't win Kherson back from Russia, which has used its numerically superior artillery with brutal effectiveness against Ukrainian forces and civilians all along the shifting frontline. Just what can Ukraine accomplish with Western-supplied artillery? Here's everything you need to know:

How are HIMARS helping Ukraine strike back at Russia?

Ukraine has been outgunned throughout Russia's invasion, and Russian forces used artillery fire to hammer Ukrainian forces and render the urban areas they were defending in the eastern Donbas uninhabitable and then impossible to defend.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"They try to crush and crush with artillery, without having particularly talented commanders or great successes in modern tactics," Ukrainian Col. Serhiy Cherevatyi tells The Wall Street Journal. "They just keep using old Soviet manuals, and the only thing that is effective in them is this use of artillery fire barrages."

The Western-supplied howitzers and then longer-range, precision artillery systems helped Ukraine hit behind Russian lines, disrupting supply lines, destroying munition stores, and decimating command centers, as the Journal explains.

Ukraine said Monday it had hit a regional headquarters of the Wagner Group, a mercenary force with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Ukrainian officials said they learned the location of the Wagner base in Popasna, Luhansk, from a photo posted on social media by a pro-Kremlin military blogger, with the address showing in one corner. "There is no more Wagner HQ in Popasna," Ukrainian lawmaker Oleksiy Honcharenko wrote on Facebook. "Thank you, HIMARS and the Armed Forces of Ukraine!"

What other steps are Ukrainian forces taking to weaken Russian defenses?

Along with the open battle along the broad frontline, Ukraine is waging a shadow war inside occupied areas. Special operations agents and partisans have "sown terror among collaborationist officials with a spate of car bombings, shootings and, Ukrainian officials say, at least one poisoning," The New York Times reports.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And while the Ukrainian military is happy to claim credit for disabling three bridges across the Dniper River, cutting the occupied city of Kherson off from Russian resupply lines east of the river, Kyiv isn't openly claiming responsibility for various strikes deep inside occupied territory.

A series of mysterious blasts rocked a Russian air base in Crimea last week, more than 100 miles from Ukrainian lines, destroying a handful of advanced warplanes, including fighter jets, bombers, and surveillance aircraft. Ukraine officially brushed off responsibility for that apparent attack or another blast at an ammunition dump in northern Crimea on Tuesday morning, but officials publicly celebrated and privately claimed credit for the explosions.

Ukrainian air defense systems and residual air force have denied Russia control of the skies, and Ukraine's naval defenses have kept Russia's Black Sea Fleet in "an extremely defensive posture, with patrols generally limited to waters within sight of the Crimean coast," Britain's Ministry of Defense said early Tuesday.

"The Black Sea Fleet continues to use long-range cruise missiles to support ground offensives but is currently struggling to exercise effective sea control. It has lost its flagship, Moskva; a significant portion of its naval aviation combat jets; and control of Snake Island," the Defense Ministry tweeted. "The Black Fleet's currently limited effectiveness undermines Russia's overall invasion strategy, in part because the amphibious threat to Odesa has now been largely neutralized. This means Ukraine can divert resources to press Russian ground forces elsewhere."

How is Russia responding?

Despite Western military aid, "Russia maintains overwhelming superiority in troop numbers and ammunition, and in recent weeks the Kremlin has moved to reinforce its military in the [Kherson] region, shifting resources there from the fighting in the eastern Donbas," the Times reports. Ukraine has laid some important groundwork for its Kherson counteroffensive, but "the cuts to supply lines have not yet eroded Moscow's overwhelming advantage in artillery, ammunition, and heavy weaponry, making it difficult, if not impossible, for Ukrainian forces to press forward without suffering enormous casualties."

Military analysts, the Journal reports, "say Ukraine lacks the manpower for a full-scale assault" on Kherson. "The real limitations the Ukrainians face is that moving forward in the combat environment today is really difficult," Phillips O'Brien, a professor of strategic studies at Scotland's University of St. Andrews, tells the Times. "Unless you have total command of the skies and the ability to clear out the area in front of your troops, those moving forward are in real danger of getting eaten away."

Does Ukraine have a chance?

Ukrainian leaders want to try to recapture Kherson before Russia engineers a referendum on the province being absorbed into Russia, or at least disrupt that effort. Unfortunately for Ukraine, their best shot at dislodging Russia involves isolating Russian forces on the western side of the wide Dnipro, which could take months, not weeks, pinning down Ukrainian forces, Russian studies and strategy scholar Michael Kofman tells the Times.

"The position that the Russian military has taken in Kherson is the least defensible of the territories they have occupied," Kofman said. "Once those bridges are gone and once the railway bridge connector into Kherson is gone, then they're going to have a very hard time getting ammunition there. They'll have to retreat to positions that, at best, are outside the city."

Russian forces can't support a ground operation without a reliable line of communications and resupply, the U.S.-based Institute for the Study of War assessed over the weekend. "Bringing ammunition, fuel, and heavy equipment sufficient for offensive or even large-scale defensive operations across pontoon ferries or by air is impractical if not impossible. If Ukrainian forces have disrupted all three bridges and can prevent the Russians from restoring any of them to usability for a protracted period then Russian forces on the west bank of the Dnipro will likely lose the ability to defend themselves against even limited Ukrainian counterattacks."

After six months of watching the Ukrainian military execute offensives, "if you were going rate them on a scale of zero to 10, how good you thought the Ukrainians were, I think I'd probably put them at about a 12 just based on how impressive they've been to us in so many different ways," a senior Pentagon official told reporters last week. "And I think, you know, we can all agree from the very beginning they have found ways to do things that we might not have thought were possible."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

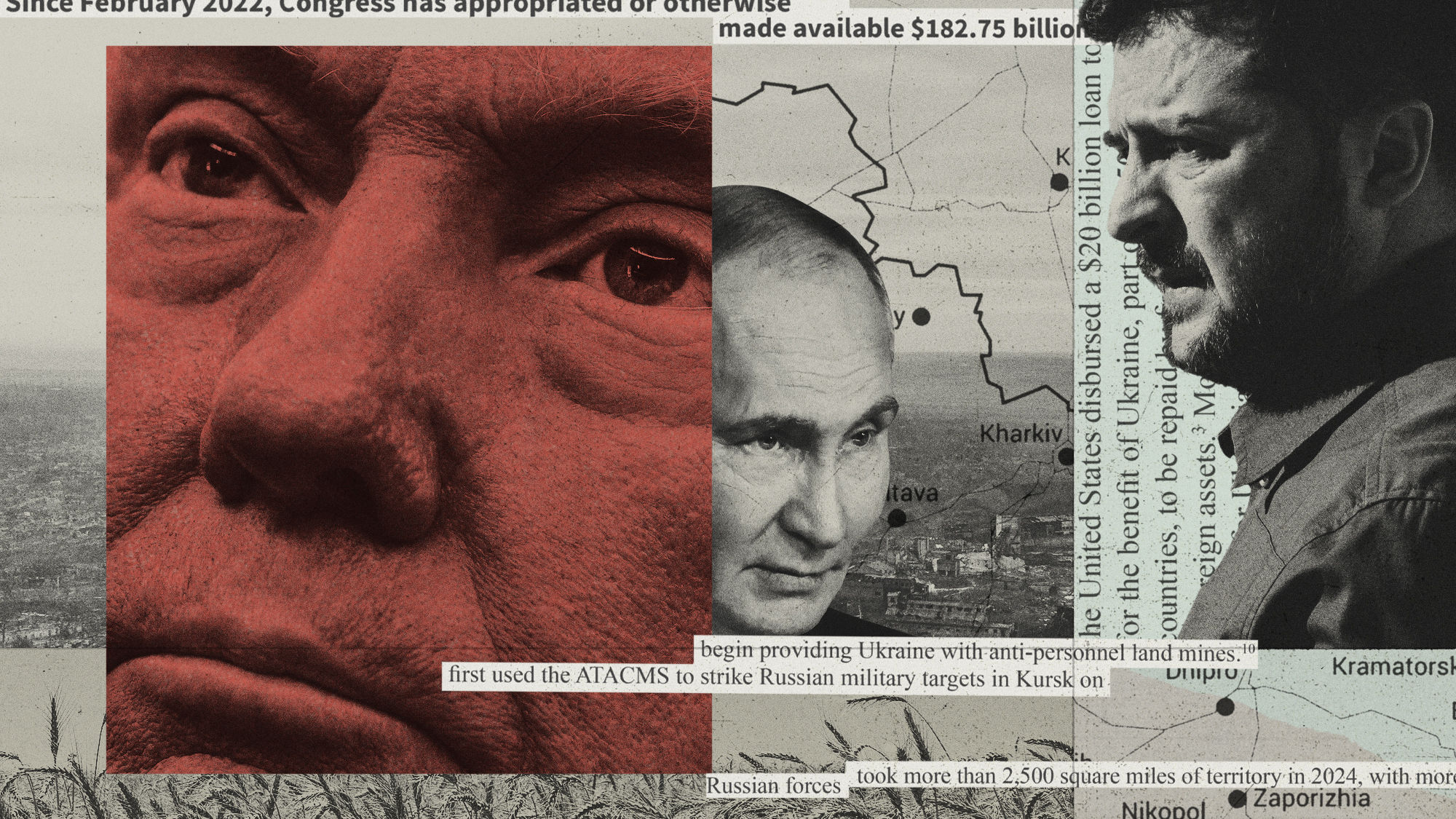

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

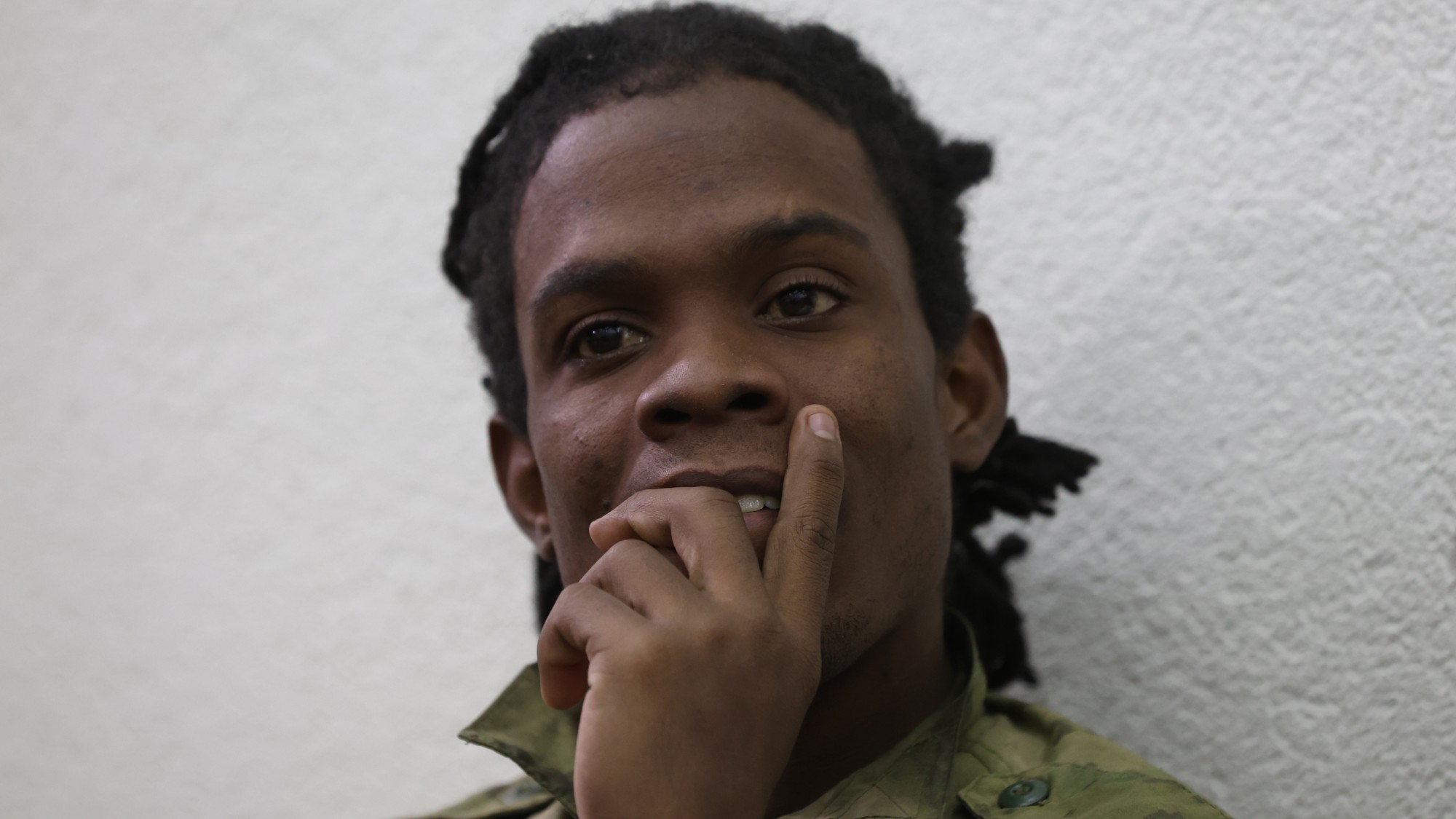

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles