Can Russia halt Ukraine's gains with jail recruits and mercenaries?

The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ukrainian forces are continuing their quick-paced counteroffensive in northeastern Kharkiv province, crossing the Oskil River — a natural break Russia had been using as a fallback defensive barrier — and securing the eastern bank, Ukraine's military command says. At the same time, Ukrainian forces in southern Kherson province are inching forward, severing Russian supply lines and striking Russian military strongholds.

"Perhaps it seems to someone now that after a series of victories we have a certain lull," Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said Sunday. "But this is not a lull. This is preparation for the next sequence."

But between Kherson and Kharkiv, Russian forces are still fighting toward Bakhmut, a city in Donetsk province that is "critical to Russia's objective of taking the rest of the mineral-rich Donbas region," The New York Times reports. "There seems an unending supply of soldiers around Bakhmut attacking Ukrainian forces," and most of the Russian soldiers are mercenaries from the Wagner Group, some of them prisoners recruited and deployed to the front lines, according to Ukrainian soldiers.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

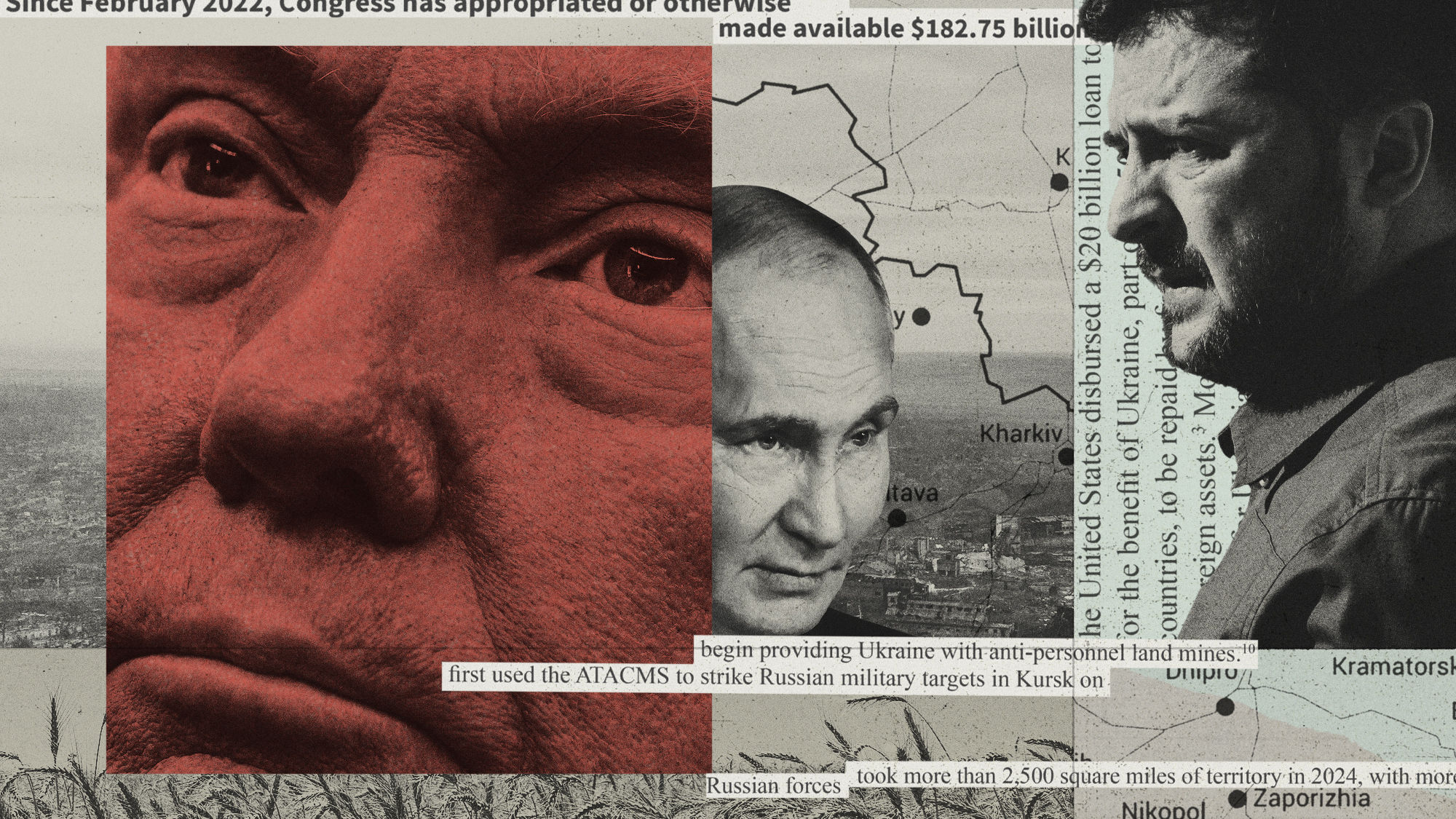

Russian President Vladimir Putin on Wednesday announced a "partial mobilization" of up to 300,000 Russian reservists, but they aren't expected to deploy to Ukraine for months. Can Russia halt its embarrassing military setbacks and replenish its attrited ranks with hired soldiers and inmates-turned-fighters?

Wagner mercenaries are bad news for Ukraine

Russia clearly needs more troops in Ukraine if it hopes to keep the territory it has seized already, much less continue making gains in the Donbas region, and if Putin won't institute a national draft, offering inmates in Russia's brutal penal colonies a shot at freedom will give him quite a few "shock troops," as reputed Wagner head Yevgeny Prigozhin said in a video released last week.

In the evidently leaked video, a man believed to be Prigozhin, a close Putin ally, tells the potential recruits that they will probably die — and they will be shot if they refuse to fight — but if they survive six months in Ukraine, their debt to Russian society will be paid and they will be free.

"Can't think of a reason why not to arm thousands, ideally tens of thousands of antisocial recidivist murderers who would suddenly be expected to follow the strictest social order conceived — an army. With an AK47 in hand," deadpanned Bellingcat's lead Russia investigator Christo Grozev.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Wagner is not the only private military company participating in Russia's war in Ukraine," but even before it started recruiting among felons in April, it stood apart for its "exceptional brutality and cruelty," as well as its resources, Aleksandra Klitina writes at the Kyiv Post. With inmate mercenaries, "their atrocities cross all human boundaries," but the Russian military appears to consider Wagner "the most professional" of its contract armies, and its expendable mercenaries have played key roles in several pivotal operations against Ukrainian troops going back to Russia's 2014 shadow invasion.

Paroled Russian inmates won't help Russia

Putin's increasing reliance on "irregular volunteer and proxy forces rather than conventional units and formations of the Russian Federation Armed Forces" suggests a "souring relationship with the military command," the Institute for the Study of War think tank assesses. "The formation of such ad-hoc units will lead to further tensions, inequality, and an overall lack of cohesiveness between forces," and it "adds little effective combat power to Russian forces fighting in Ukraine."

"Professional military staff are likely to confront behavioral issues among recruited prisoners, especially considering the likely prevalence of prisoners convicted of violent crimes, narcotics, and rape," ISW reports, but the other ad-hoc militias also have problems that will make "conflict and poor unit coordination more probable. The one thing they have in common is wholly inadequate training and preparation for combat." In other words, ISW says, "the reported arrival of increasing numbers of irregular Russian forces on the battlefield has had little to no impact on Russian operations."

Moreover, the Kremlin's reliance on Wagner and its prisoner recruits, plus accelerated training and cadet graduations at Russian military academies, show that "the impact of Russia's manpower challenge has become increasingly severe," Britain's Ministry of Defense says. "The acceleration of officer cadets' training, and Wagner's demand for assault troops suggests that two of the most critical shortages within the military manning crisis are probably combat infantry and junior commanders."

And it's not just an issue of troop levels. "The Russians are apparently directing some of the very limited reserves available in Ukraine" to "meaningless offensive operations around Donetsk City and Bakhmut instead of focusing on defending against Ukrainian counteroffensives that continue to advance," ISW writes. That "might indicate that Russian theater decision-making remains questionable."

On the flip side, Ukraine's military has been planning and executing quality operational design, especially against the "bumbling and incoherent Russian defensive scheme to the east of Kharkiv," retired Australian Maj. Gen. Mick Ryan writes. "The concurrent Ukrainian offensives have totally compromised the Russian operations in the Donbas" and introduced "a larger psychological issue with Russian soldiers and commanders fighting in the east."

Russia has few good options in deploying its depleted forces, Ryan adds, and "because of a Russian reinforcement 'shell game', it is possible that we could see cascading Russian tactical withdrawals and failures in various regions as a consequence."

Russia doesn't have to win to cause Ukraine pain

"In the last seven days, Russia has increased its targeting of civilian infrastructure even where it probably perceives no immediate military effect," Britain's Ministry of Defense reported Saturday. "As it faces setbacks on the front lines, Russia has likely extended the locations it is prepared to strike in an attempt to directly undermine the morale of the Ukrainian people and government."

The Ukrainians, with their "incredible bravery" and "incredible determination," are not "losing a war, and they're making gains in certain areas," President Biden told CBS 60 Minutes in an interview that aired Sunday. But "winning the war in Ukraine is to get Russia out of Ukraine completely and recognizing the sovereignty. They're defeating Russia. Russia's turning out not to be as competent and capable as many people thought they were gonna be. But winning the war? The damage it's doing, and the citizens, and the innocent people are being killed, it's awful hard to count that as winning."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

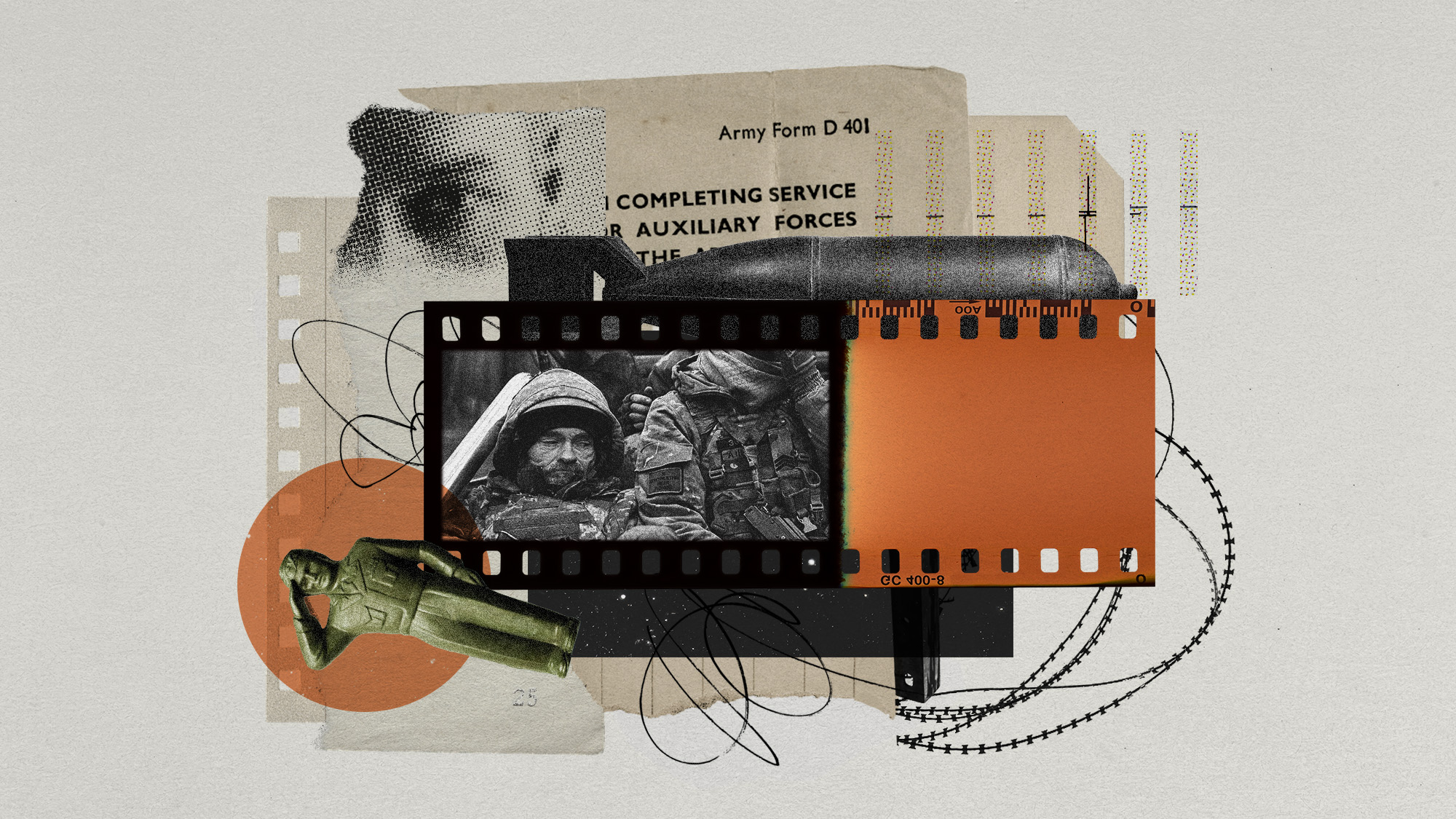

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

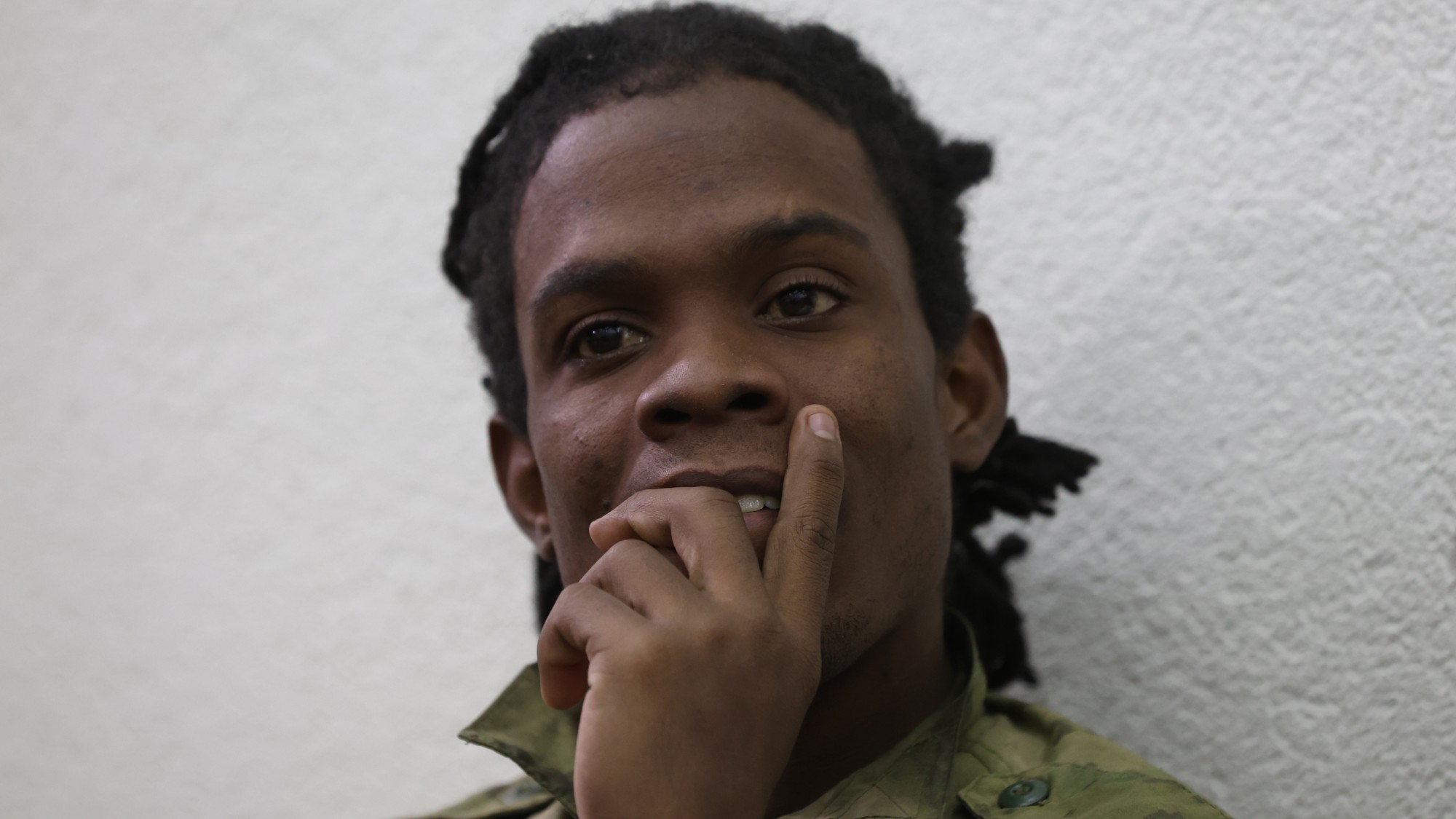

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles