Universal donor blood is 'close' to reality

Scientists identify 'cocktail' of enzymes that destroy harmful antigens

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Attempts to create universal donor blood have taken a "decisive step forward" after scientists discovered ways to significantly reduce the risk of a negative reaction.

A "cocktail" of bacterial enzymes identified by researchers at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) and Lund University in Sweden effectively removes antigens, according to findings published in the scientific journal Nature Microbiology.

Around 50% of people naturally have type O or "universal" blood, but those with type A, type B and the rarer type AB blood can currently only give and receive blood from their own group. This is because antigens, the chains of sugars attached to the body's red blood cells, take on different forms in type A and type B blood and can "trigger life-threatening immune reactions when transfused into non-matched recipients", DTU said in a press release.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists have "experimented with enzymes" to remove antigens from blood for decades, said The Economist. But the new combination appears to be effective on "lengthened antigen sugar chains, called extensions, that are not targeted by current enzymes".

"We are close to being able to produce universal blood from group B donors, while there is still work to be done to convert the more complex group A blood," said Professor Maher Abou Hachem, who led the study.

The research team will work on the project for another three and a half years, after which they hope to progress to human clinical trials.

The ability to convert donor blood into a universal type would "markedly reduce the logistics and costs currently associated with storing four different blood types", said DTU.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Every drop counts. Blood banks have warned of dwindling supplies in countries including the US and UK, and "ageing populations are expected to increase the demand for blood yet further", said The Economist.

Rebecca Messina is the deputy editor of The Week's UK digital team. She first joined The Week in 2015 as an editorial assistant, later becoming a staff writer and then deputy news editor, and was also a founding panellist on "The Week Unwrapped" podcast. In 2019, she became digital editor on lifestyle magazines in Bristol, in which role she oversaw the launch of interiors website YourHomeStyle.uk, before returning to The Week in 2024.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

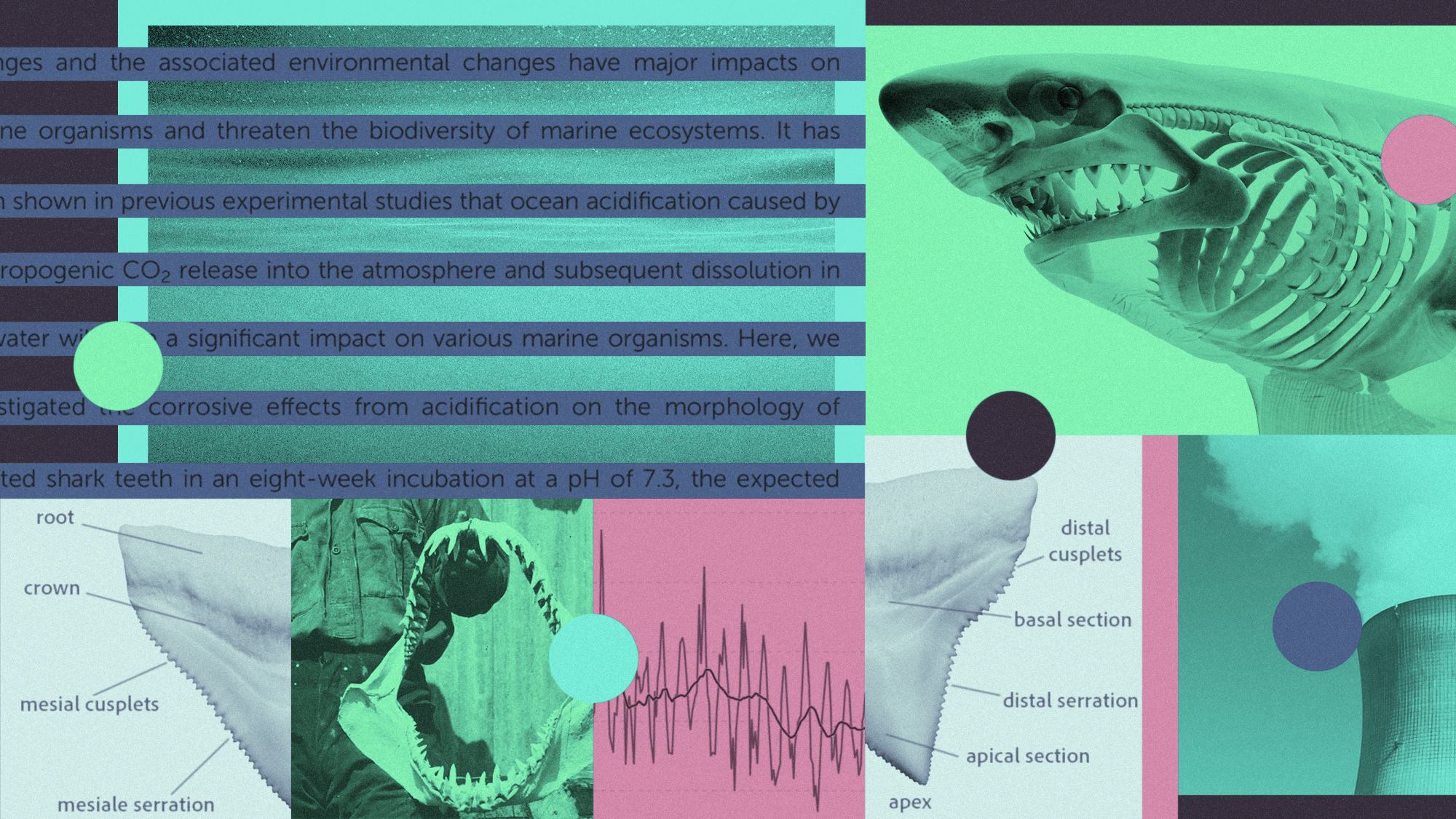

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime