How do vessels get lost at sea?

Finding missing vessels in the ocean is no easy task

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

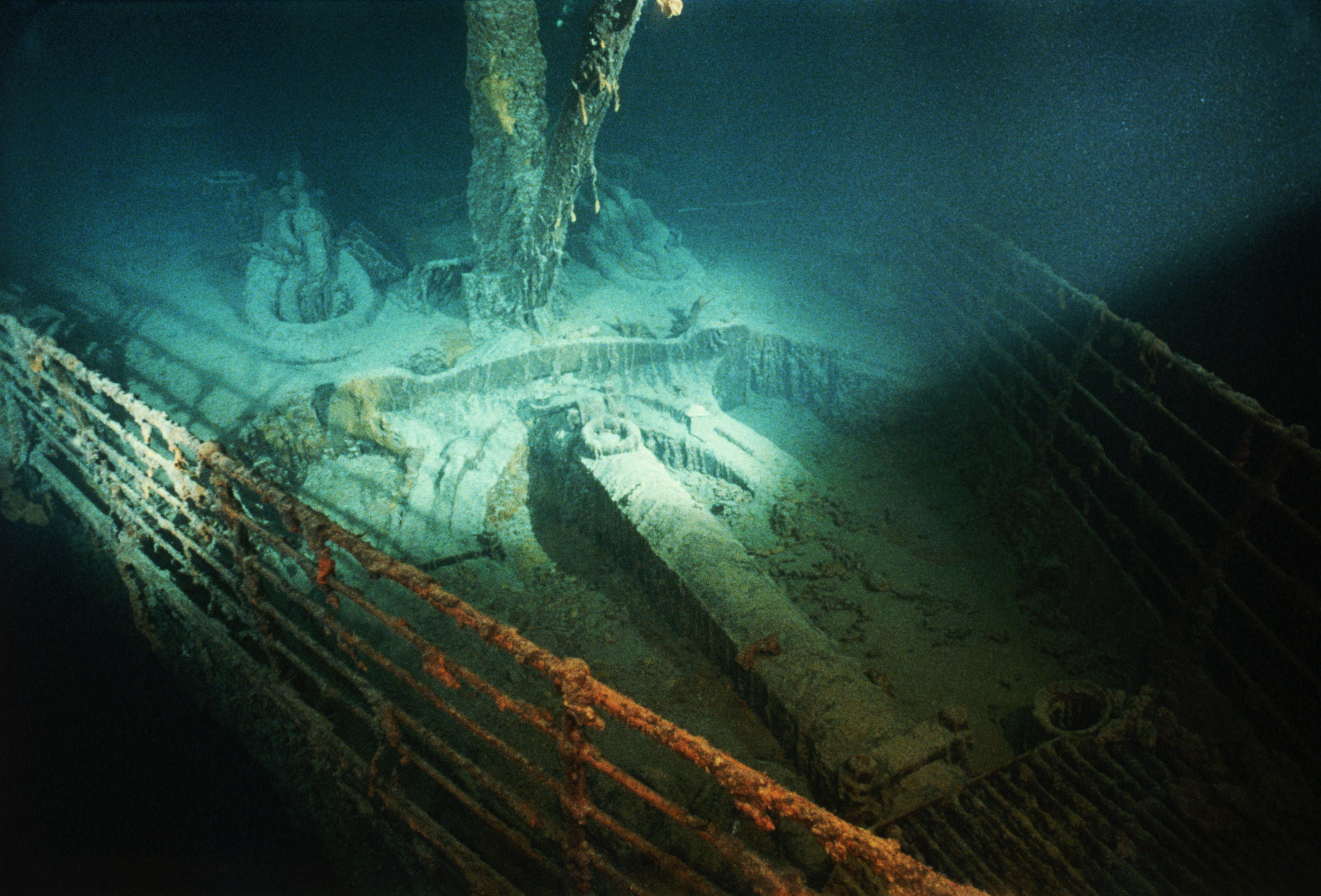

A submersible en route to the ruins of the shipwrecked RMS Titanic lost contact with its mother ship and was declared missing with five people aboard. After days of searching, all that was found was debris near the site of the Titanic believed to be the submersible. Following the finding, OceanGate Expeditions, the company responsible for the expedition, declared that all aboard had "sadly been lost." Finding such a vessel is a "very difficult search," according to The New York Times, and sea rescues have been historically rare. How do such vessels get lost, and why are they so difficult to find?

How do vessels go missing?

Ocean rescues are some of the hardest to be successful because of the number of variables involved in locating a vessel. The ocean is incredibly vast and not static the way land is. In the case of the missing submersible, without any communication or way of tracking its location, the position of the vessel could be anywhere in an area double the size of Connecticut, reported CBS News. The vessel is also only 22 feet long, making spotting very difficult, per the Times.

The ocean has always been notoriously difficult to navigate as well as locate debris in. The Titanic wreckage was only discovered over 70 years after the tragedy took place because of how deep in the Atlantic Ocean it was (approximately 13,000 feet) and the lack of technology to navigate such depths. More recently, the remains of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 have yet to be found despite going missing in 2014. The search for the missing submersible has "echoes of the futile search" for the missing flight, according to CNN. "In [the search for] Malaysia Airlines, we heard banging quite often, and it always turned out to be something different," David Gallo, a senior adviser for strategic initiatives for RMS Titanic Inc., told CNN.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most vessels, like the submersible, are small compared to the expansive ocean, making them difficult to spot even when on the surface and even harder when submerged. Also, communication systems are different in water compared to the air because the density of water blocks electromagnetic waves, so GPS systems don't work. Instead, rescuers need to rely on sonar, which uses sound waves. However, Jamie Pringle, a reader in forensic geosciences at Keele University in England, told Forbes that a "specialized" and "very narrow beam" would be needed to locate such a small vessel.

Why are vessels so difficult to find and retrieve?

Aside from the vast size of the ocean, there are several perils and logistical struggles involved in deep-sea travel. "The only reason organisms can survive at that depth is because they're more or less the same density as the water around them, so they don't get deformed like us air-breathing creatures," Jules Jaffe, a research oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, told Scientific American. As we go deeper into the ocean, visibility decreases, temperatures cool, and the water pressure becomes unsuitable for humans. High levels of pressure make it difficult to pull vessels out even if they're found.

The deepest successful ocean rescue was only 1,575 feet below the surface, far less than the missing submersible. "Going undersea is as, if not more, challenging than going into space from an engineering perspective," explained Eric Fusil, an associate professor at the University of Adelaide, to Forbes. In addition, "there are very few vessels that can get that deep," Alistair Greig, a professor of marine engineering at University College London, said to Forbes. "If it has gone down to the seabed and can't get back up under its own power, options are very limited."

"We have better maps of the moon and Mars than we do of our own planet," Dr. Gene Feldman, an oceanographer emeritus at NASA, told CNN. He added that a "very small percentage of the deep ocean, and even the middle ocean, has been seen by human eyes." Overall, the ocean is a frontier difficult for humans to navigate through, making rescue and recovery operations expensive, difficult and time-consuming. "It's not hard to get stuff down," Jaffe said. "Getting the stuff back is the problem."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

5 of the most invasive animal species on the planet

5 of the most invasive animal species on the planetSpeed Read Invasive species are a danger to ecosystems all over the world

-

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancy

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancySpeed Read Climate change is worsening air quality globally, and there could be deadly consequences

-

How climate change is impacting the water cycle

How climate change is impacting the water cycleSpeed Read Rain will likely continue to be unpredictable

-

Why spotted lanternflies are back and worse than ever

Why spotted lanternflies are back and worse than everSpeed Read It's time to get squashing!

-

Peatlands are the climate bomb waiting to explode

Peatlands are the climate bomb waiting to explodeSpeed Read The destruction of peatlands can cause billions of tons of carbon to be released into the atmosphere, worsening the already intensifying climate crisis

-

Wind-powered ships are back. But will they make an impact?

Wind-powered ships are back. But will they make an impact?Speed Read The maritime industry is eyeing a pivot back to basics

-

The growing threat of urban wildfires

The growing threat of urban wildfiresSpeed Read Maui's fire indicates a phenomenon that will likely become more common

-

A summer of shark attacks

A summer of shark attacksSpeed Read A spate of shark attacks off the Northeast coast has swimmers and surfers on edge. What’s behind the biting spree?