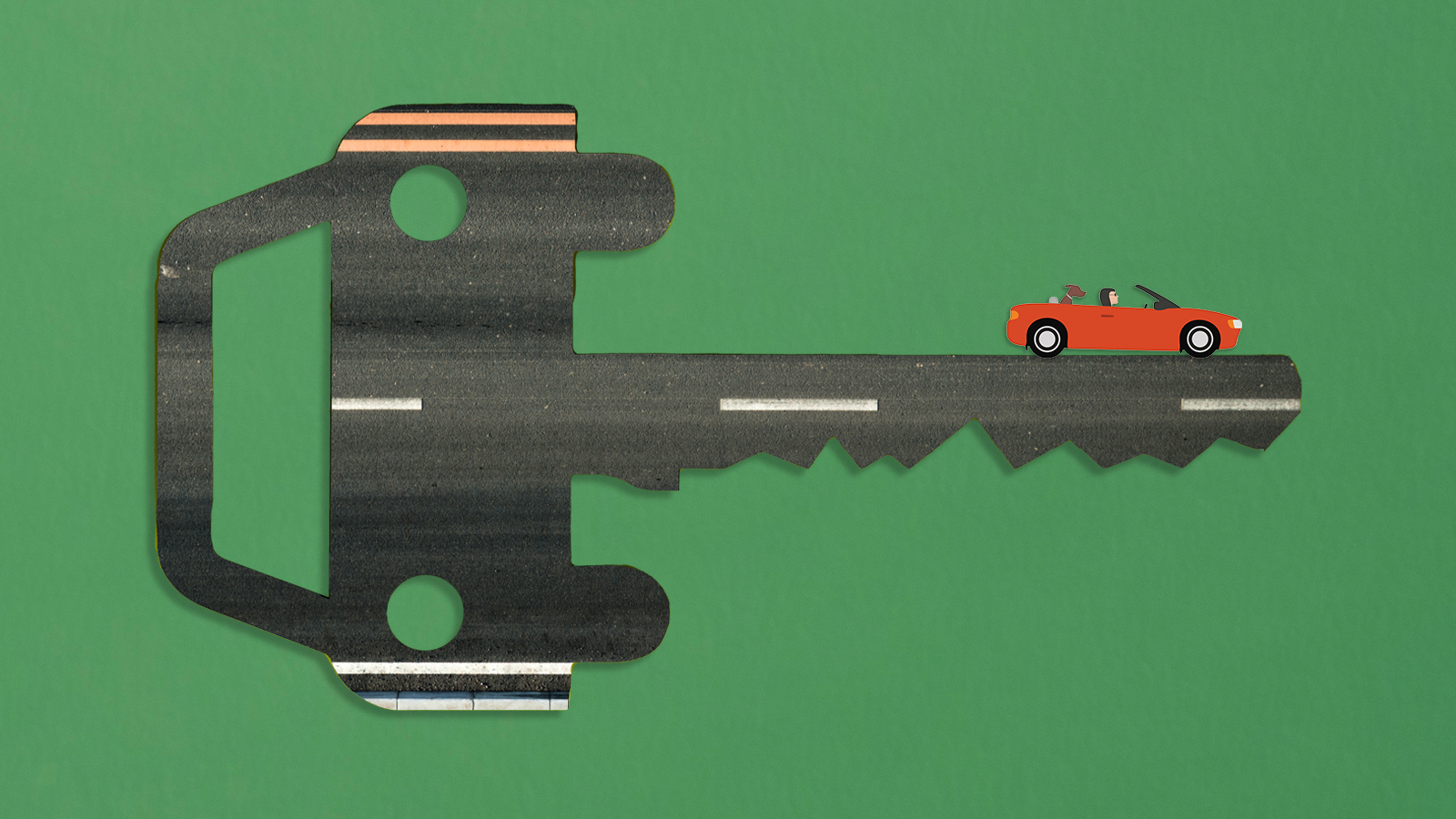

Why U.S. teens aren't getting their driver's licenses

Are they avoiding adult responsibilities?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Getting a driver's license used to be a sign of burgeoning independence for America's teens. That may not be the case anymore. The Washington Post reports that 16- and 17-year-olds are driving much less than their predecessors. "Unlike previous generations, they don't see cars as a ticket to freedom or a crucial life milestone." And that reluctance to get behind the wheel is lasting into young adulthood: Just 80 percent of adults in their early twenties had their licenses in 2020 — down 10 percent from 1997. The trend has drawn some consternation from their elders. The real reason teens aren't driving, The Atlantic's Tom Nichols writes, is "because they're not growing up, and because you'll drive them anywhere they need to go." Why aren't teens getting on the road? Here's everything you need to know:

Are teens really not driving anymore?

Not as much, certainly. The trend has been developing for a while now. In 2013, National Geographic noted a Michigan study showing that the percentage of 19-year-olds with a license had fallen from 87 percent in 1983 to 70 percent in 2010 — and that the percentage of 17-year-old drivers fell from 69 to 43 percent during the same time period. And The Wall Street Journal in 2019 reported that while nearly half of 16-year-olds were driving in the 1980s, just a quarter were by 2017. The Washington Post, drawing on data from the Federal Highway Administration, suggests the number remained at about 25 percent in 2020.

Why did teens stop driving?

There really isn't any single reason that experts have hit on. That 2013 Michigan study surveyed young adults and found a wide range of reasons they weren't getting licenses. Respondents said they were too busy, or that driving was too expensive, or that they preferred other forms of transportation. Economics seems to play a role, PBS reported in 2017: Teens just don't get summer jobs as often as they did even 20 years ago, which means both that they have less need for a license and less money to pay for driving expenses. Those expenses can add up: They include the cost of the car, gas, and insurance, the last of which is much higher-priced for young drivers. And America's continuing urbanization might also play a part — young people increasingly live in cities and suburbs with access to mass transit, making cars less necessary.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Is technology behind all of this?

It may play a role. In 2012, the University of Michigan's Michael Sivak said the percentage of teen drivers "was inversely related to the proportion of Internet users." At that point, at least, kids just weren't getting away from their screens to hang out with their friends IRL. "Virtual contact, through electronic means, reduces the need for actual contact." It's worth pointing out here that while a number of news stories in recent years have suggested that social media is responsible for the trend, they don't often cite any research or studies proving the point. But also it's true, as the Washington Post points out, that "Gen Zers have the ability to do things online — hang out with friends, take classes, play games — which used to be available only in person." And when they do need to be there, app-driven services like Uber and Lyft often provide the ride.

Did policy changes make a difference?

This seems a likelier explanation. Back in 2008, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety urged states to raise the driving age from 16 up to 17 or even 18, CBS News reported at the time. "The bottom line is that when we look at the research, raising the driving age saves lives," said Adrian Lund, the group's president. (The institute's website says that teens crash four times as often as older drivers.) And a few states did indeed make it tougher: The next year, for example, Kansas raised the minimum age for unrestricted driver's licenses from 16 to 17. And the barriers to getting those licenses — even when teens met the age requirement — have gotten higher. The Journal of Safety Research reported in 2017 that all but seven states "upgraded" their licensing requirements between 1996 and 2006, adding "minimum learner periods, minimum practice hour requirements, or night or passenger restrictions." It's just not as easy to get a license as it used to be.

Should we worry about kids' independence?

There certainly seems to be some angst about the topic. Google information about the decline of teen driving, and the search engine will offer related topics like "son has no interest in driving," and "refusing to learn to drive." For some observers, the trend seems related to the broader tendency of young Americans to delay major life milestones like getting married and buying a home. But it may simply presage a broader shift away from driving: A 2021 overview in the journal Transportation Research found that millennials — the first generation to take its time getting a license — still drove fewer miles than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers, long after they had reached adulthood.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royalty

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royaltyThe Week Recommends The five-star birthplace of the famous Sachertorte chocolate cake is celebrating its 150th anniversary

-

Where to begin with Portuguese wines

Where to begin with Portuguese winesThe Week Recommends Indulge in some delicious blends to celebrate the end of Dry January

-

Climate change has reduced US salaries

Climate change has reduced US salariesUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The video game franchises with the best lore

The video game franchises with the best loreThe Week Recommends The developers behind these games used their keen attention to detail and expert storytelling abilities to create entire universes

-

The buzziest movies from the 2023 Venice Film Festival

The buzziest movies from the 2023 Venice Film FestivalSpeed Read Which would-be Oscar contenders got a boost?

-

America's troubling school bus driver shortage

America's troubling school bus driver shortageSpeed Read Kids are heading back to school, but they might be having trouble getting a ride

-

5 college admissions trends to watch out for this year

5 college admissions trends to watch out for this yearSpeed Read College advisers and admissions experts say these trends will shape the 2023-2024 admissions cycle

-

What's going on with Fyre Festival II?

What's going on with Fyre Festival II?Speed Read Convicted felon Billy McFarland claims the music festival will happen, for real this time

-

The answer to rising home prices: smaller homes

The answer to rising home prices: smaller homesSpeed Read Builders are opting for fewer rooms and more attached styles as frustrated homebuyers look for affordable options

-

5 illuminating books about the video game industry

5 illuminating books about the video game industrySpeed Read Cozy up with a few reads that dig into some of the most fascinating parts of video game history

-

Everything we know about the final season of 'Stranger Things'

Everything we know about the final season of 'Stranger Things'Speed Read The Netflix hit will turn things up to eleven in its final bow ... eventually