Children's mental health: do we care nearly enough?

As 25,000 children are hospitalised every year for self-harming, MPs are finally asking the big question

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

THE subject of child mental health is very close to my heart. I was a depressed teenager. I had emotions I could neither name nor deal with, but which came out in strange behaviour such as controlled eating and uncontrollable spending.

There were no obvious causes: I had loving parents, I wasn’t bullied, I had lots of kind friends. But the adults in my life were hard-working people who didn’t really “do” emotions and I was left trying to work out “just what do you have to be depressed about” all by myself.

I finally found the courage to see my GP when I was 20. Before this I simply hadn’t felt brave enough to take up a doctor’s time with my “emotional” problems. I remember I almost bolted from the waiting room, but things were bad – desperate – enough that I stayed put. My GP listened, he got me help. He very probably saved my life.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I might not have been so lucky if I’d been born later. Although mental health has lost some of its stigma and there is more recognition, it is harder today to get proper, sustained, appropriate help, especially if you’re young.

This is why child and adolescent mental health is the subject of a new Commons Health Committee inquiry, announced last month, that aims to look at the causes of mental health problems among the young - and the quality of the services available to them.

It’s been ten years since any survey, of any kind, has looked into child mental health, which is shocking when you consider how much has happened in the past decade.

Not least, look at the rise of social media and how it’s taken bullying to new, and at times, devastating levels. There’s more. Children today have to contend with more family breakdown (the UK has one of the highest rates in the western world), more ways to be bullied, more pressure to achieve at school and the depressing fact that, at the end of your high-pressured education, we’re in the middle of a recession and unemployment amongst the young is at 20 per cent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Although it’s impossible to know whether there is more of a problem now than ever before or if there simply are more people presenting with these problems, the facts are currently these: one in ten children between the ages of one to 15 has a mental health disorder. One in three children in every classroom has a diagnosable mental health disorder. One in five young adults show symptoms of an eating disorder and 25,000 children are hospitalised each year because of self-harming.

That would be bad enough if there were the services to prop and mop up. But there are fewer and fewer as cuts are made to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) resources. Last year, two-thirds of local authorities reported to Young Minds, the UK’s leading charity for children’s mental health and well-being, that their CAMHS budgets had been reduced – one of them by a whopping 41 per cent.

Practically, what does this mean? Well, child and adolescent mental health is regarded as a four-tier system. Tier 1 - the bottom tier -covers GPs, health visitors, school or university counsellors: services that are, or should be, readily available to all. These are the people who can catch problems early on: the child who may be dealing with a difficult situation at home before they start cutting themselves or run away, for instance. Tier 2 might cover a couple of sessions with a counsellor to assess the situation.

It is at the bottom two tiers that most of the cuts have been made, which means that there are now fewer people to help in the initial stages where help might be easier, and cheaper, to give. Which means that a nervous teenager looking for that first bit of help might simply have no one to go to.

It is, like so many cuts, short-sighted because children not seen at an early age won’t just magically get better, but may go on to put even greater strain on tiers 3 and 4, which is when we get into specialist mental health teams in hospitals: psychiatrists, in-patient wards, that sort of thing.

This is why there are now situations where children are detained in police cells under the Mental Health Act “for their own safety” because there is simply nowhere else to put them. Last year there were 305 such cases. Or children placed in adult psychiatric units, which can be deeply traumatic for a young person at a time when they are already deeply vulnerable. Or if treatment is indeed available, it might be at an in-patient unit many miles from home.

Just last month, shadow health minister Liz Kendall spoke in the House of Commons about one of her under-18 constituents who was told that there was not a “single child and adolescent mental health bed in the NHS or in the independent sector anywhere in the country”.

But why does any of this matter? Why is a Commons inquiry important? Because good mental health is just as important as good physical health: patterns and problems set in childhood can go into adulthood.

This impacts on all of us. Scratch almost any news story, from the violent to the sad to the desperate, and there will be a mental health issue – diagnosed or not – at the heart of it. Last week, I had two phone calls from two different friends. One’s teenage daughter was self-harming, the other’s nephew had just attempted suicide, aged 19. “What help is he getting?” I asked. “There isn’t anything at the moment,” replied my friend. “He’s been sent home, drugged up to the eyeballs until they can get him on the waiting list.”

Who knows if he’ll make it to be 20, the age at which, thanks to a great GP and proper therapy, my life really started.

Young Minds helpline: 0808 802 5544

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youth

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youthIn The Spotlight Obsession with beating biological clock identified as damaging new addiction

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

The app tackling porn addiction

The app tackling porn addictionUnder the Radar Blending behavioural science with cutting-edge technology, Quittr is part of a growing abstinence movement among men focused on self-improvement

-

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypes

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypesUnder the radar They could lead to more accurate diagnosis and care

-

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatine

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatineThe Explainer Popular fitness supplement shows promise in easing symptoms of everything from depression to menopause and could even help prevent Alzheimer's

-

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxiety

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxietyThe Week Recommends You can soothe your nervousness about flying before boarding the plane

-

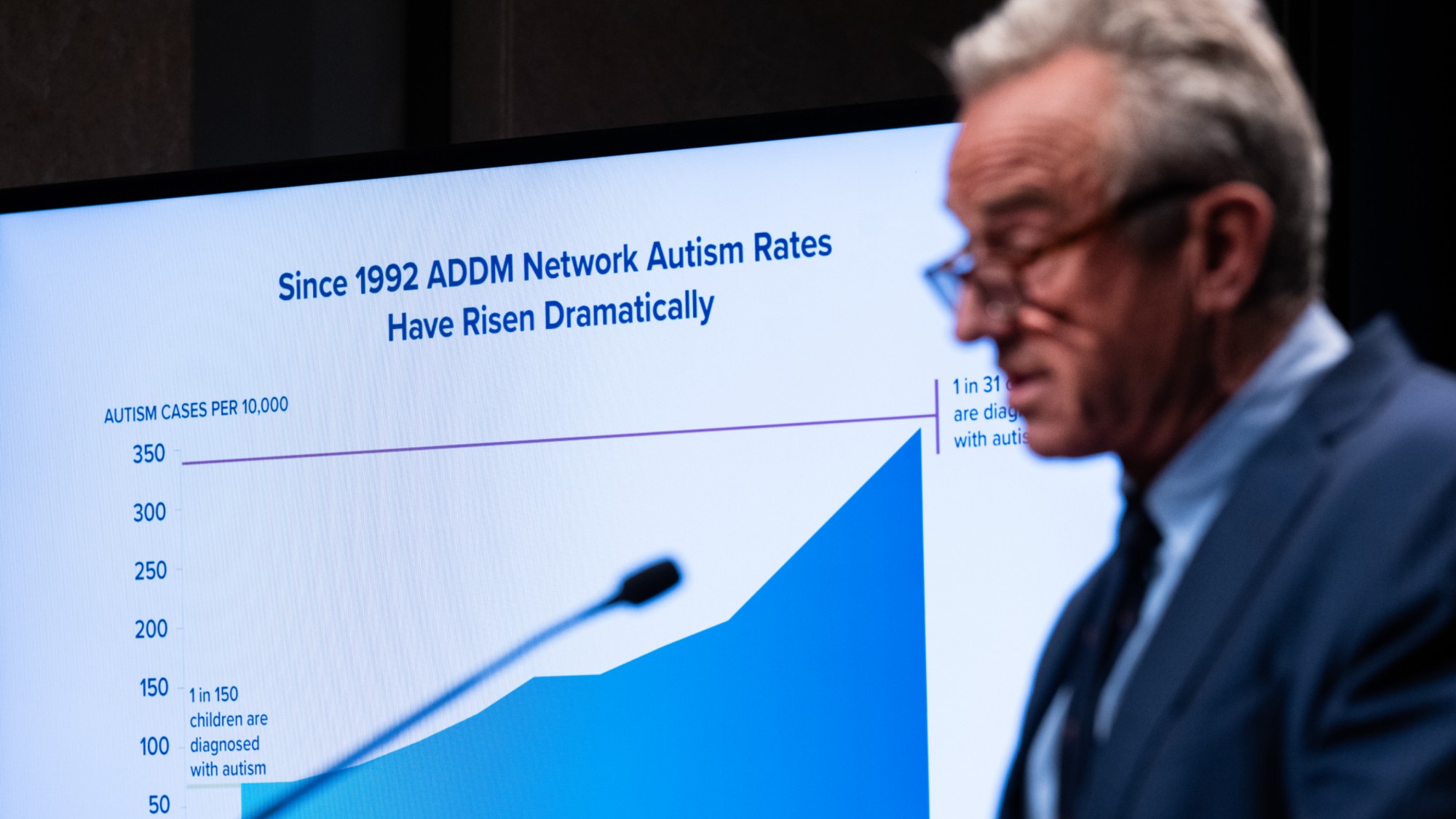

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchers

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchersIn the Spotlight Many of Kennedy's assertions have been condemned by experts and advocates

-

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?Talking Point Issues at 'the milder end of the spectrum' may be getting wrongly pathologised