BBC says it has a duty to play 'Ding Dong' song - but does it?

Broadcaster's argument for playing anti-Thatcher song contradicts its history of censorship

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

THE BBC has argued it is obliged to play Ding Dong, the Witch is Dead because the pop charts are a "historical and factual" account of what the public is buying. That sounds like a decent enough reason to broadcast the Judy Garland song sent rocketing up the charts by anti-Thatcher protestors. Decent, that is, until you examine the corporation's track record for censoring and banning popular records.

The fact is the Beeb has a long and (in)glorious history of ignoring the public's taste and either pulling songs off the air or changing their lyrics. Its reasons have ranged from an excess of sentimentality to sexual content, bad language and – a tricky one, this – the mere fact that the song's title or lyrics might be construed as offensive in the context of current events and wars in particular.

The most famous example of the BBC imposing a ban on a hit record is The Sex Pistols' God Save the Queen in 1977. To be fair, the song was a censor's dream. The title was bitterly ironic, the lyrics were overtly offensive - "made you a moron" – Jamie Reid's cut-and-paste cover art was deemed outrageous and the timing of its release during the Queen's Silver Jubilee was (rightly) construed as a raised finger to the British establishment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But it doesn't take an incendiary record like God Save the Queen to stir the BBC into action. When Britain goes to war, the most ineffectual song can find itself in the crosshairs – excuse the phrase – of the corporation's censors.

In 1982, the New Zealand group Split Enz released a song called Six Months in a Leaky Boat, a catchy tune inspired by the time it took to sail from England to the Antipodes. Unluckily for the band, Margaret Thatcher had recently dispatched another fleet of English boats on a long sea voyage and BBC bosses decided the song would be an inappropriate soundtrack to Britain's efforts to reclaim the Falklands.

Nine years later, a harmless pop song by Lulu called Boom Bang-a-Bang was banned by the BBC during another war, this time in the Persian Gulf. The broadcaster believed the title – a reference to Lulu's heartbeat – could be mistaken for the sound of exploding munitions. The same fate befell 10CC's Rubber Bullets and Cutting Crew's I Just Died in Your Arms Tonight.

You could argue that protecting the public's ears from pop songs that may appear offensive against the backdrop of a war is a sensible precaution for a publicly-funded broadcaster. Yet it seems a curious sensibility given that the soldiers doing the actual fighting often use pop music to prepare themselves for combat, a phenomenon laid bare in the 2004 documentary Soundtrack to War.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The BBC doesn't just ban records in war time, either. Frankie Goes to Hollywood's single Relax was at No. 6 on the chart when the BBC pulled the plug due to its "sexual references". The Kinks' Lola was banned until the overtly commercial reference to Coca-Cola was changed to cherry Cola. And the Shamen's Ebeneezer Goode was removed from playlists because its chorus implied – stated would be a better description - that 'E' – the drug ecstasy – was "good".

The BBC says it may ask a reporter to "explain the context" if it plays Ding Dong the Witch is Dead on Sunday's Radio One chart show. That seems like a limp compromise that will please neither side of the argument. And you might ask why the broadcaster didn't get a reporter to "explain the context" of God Save the Queen back in 1977.

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

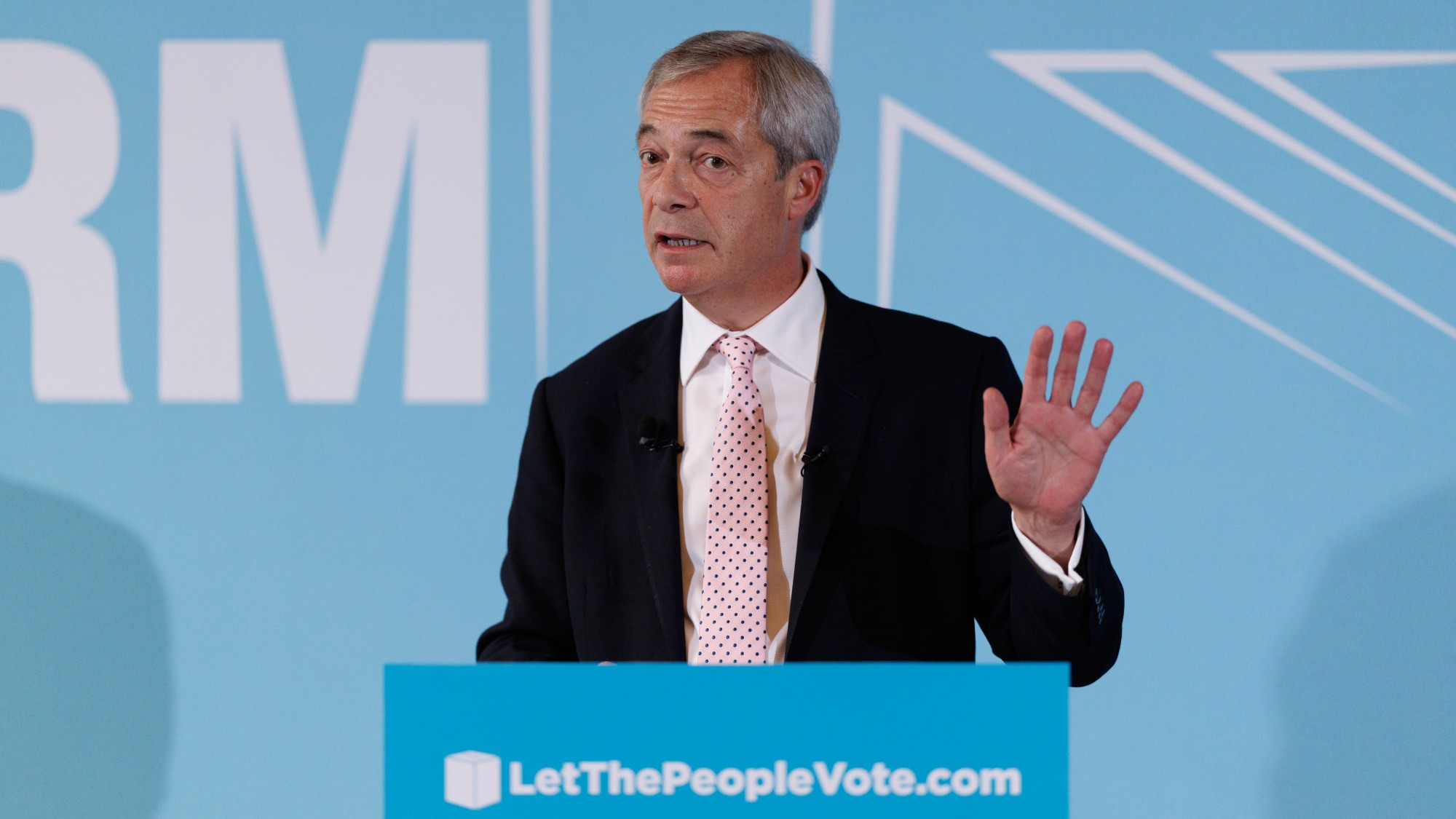

Nigel Farage’s £9mn windfall: will it smooth his path to power?

Nigel Farage’s £9mn windfall: will it smooth his path to power?In Depth The record donation has come amidst rumours of collaboration with the Conservatives and allegations of racism in Farage's school days

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

‘The business ultimately has a customer base to answer to’

‘The business ultimately has a customer base to answer to’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

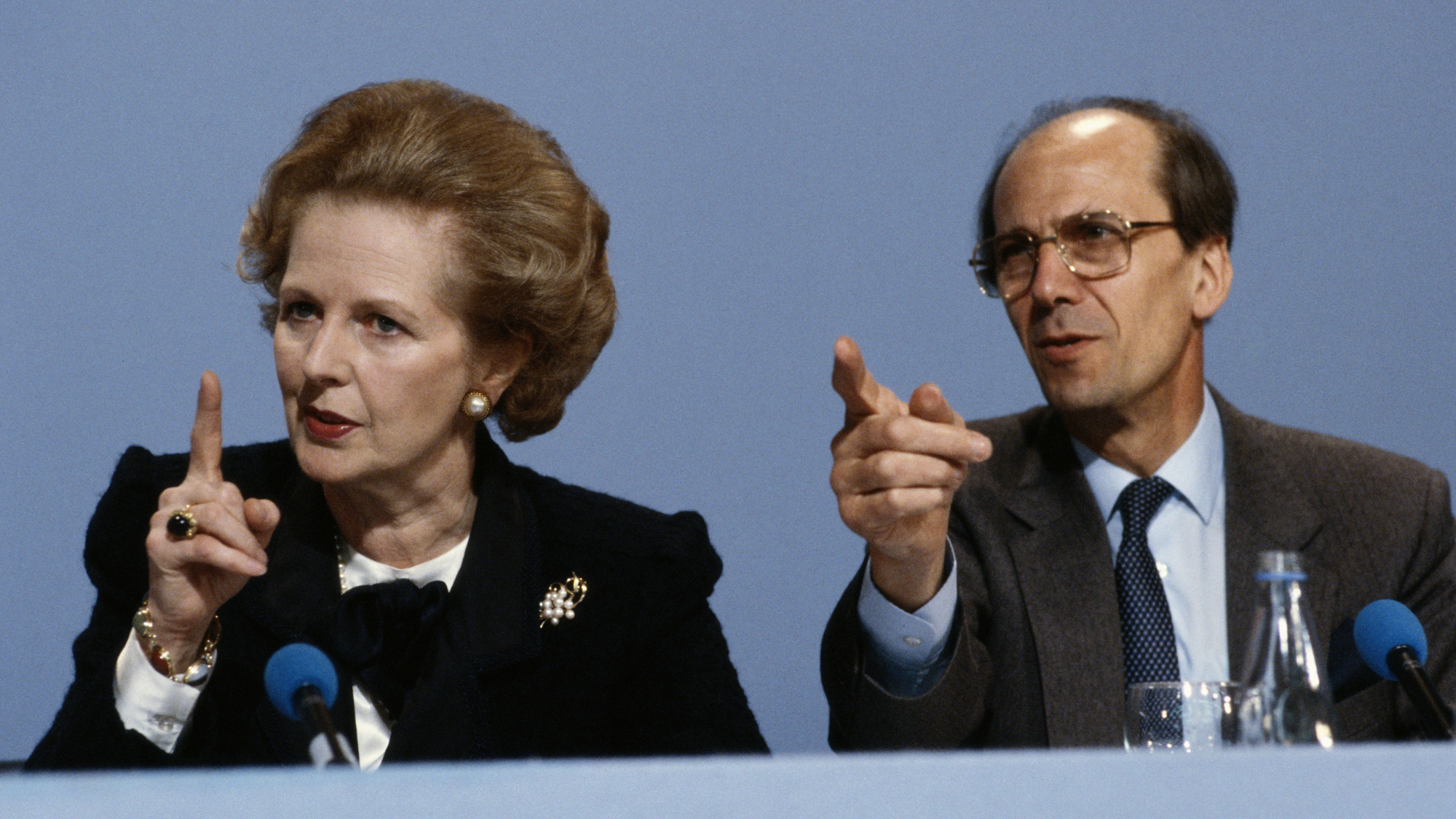

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcer

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcerIn the Spotlight Former Conservative Party chair has died aged 94

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance