In California, K-12 students who refuse to wear a mask will be barred from campus

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

No mask, no school.

Under California's new state regulations announced on Monday, students in Kindergarten through 12th grade who refuse to wear masks inside their classrooms and school buildings this fall will be prohibited from coming on campus. There will be exceptions for kids who have special needs or disabilities, and they will receive non-restrictive alternative face coverings on a case-by-case basis. All schools and buses will have masks to hand out to kids as needed, and face coverings will be optional outside. If a student won't wear a mask, the state regulations say, then "schools should offer alternative educational opportunities."

In California, 99 percent of school districts have said they will fully reopen in the fall for in-person classes, and Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond told the Los Angeles Times the state's health rules seem to be "a safe course for ensuring that every student can come back to school in the fall. I certainly see the logic of it." Masks are especially important when there is not ample room for physical distancing, he added, and in cases where not everyone in a room is vaccinated; only people 12 and older are eligible for the coronavirus vaccine, and not everyone who can get vaccinated has done so.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On Friday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released recommendations saying that schools could allow vaccinated students to go to class and not have to wear a mask. This wasn't a mandate, though, and California decided to take a stricter approach.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

Penn wipes trans swimmer records in deal with Trump

Penn wipes trans swimmer records in deal with Trumpspeed read The University of Pennsylvania will bar transgender students from its women's sports teams and retroactively strip a trans female swimmer of her titles

-

Supreme Court may bless church-run charter schools

Supreme Court may bless church-run charter schoolsSpeed Read The case is 'one of the biggest on church and state in a generation'

-

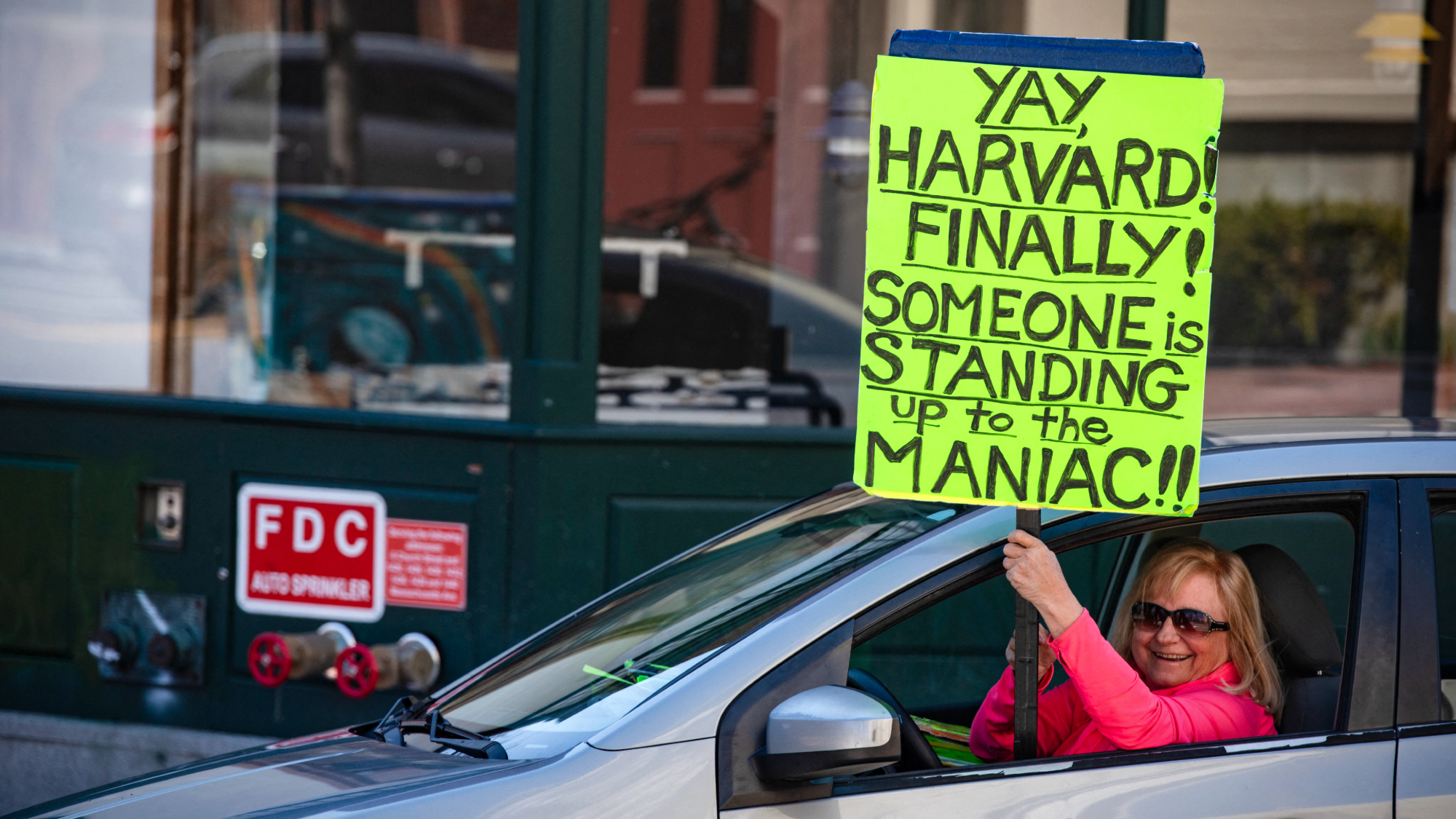

Harvard sues Trump over frozen grant money

Harvard sues Trump over frozen grant moneySpeed Read The Trump administration withheld $2.2 billion in federal grants and contracts after Harvard rejected its demands

-

Harvard loses $2.3B after rejecting Trump demands

Harvard loses $2.3B after rejecting Trump demandsspeed read The university denied the Trump administration's request for oversight and internal policy changes

-

USC under fire for canceling valedictorian speech

USC under fire for canceling valedictorian speechSpeed Read Citing safety concerns, the university canceled a pro-Palestinian student's speech

-

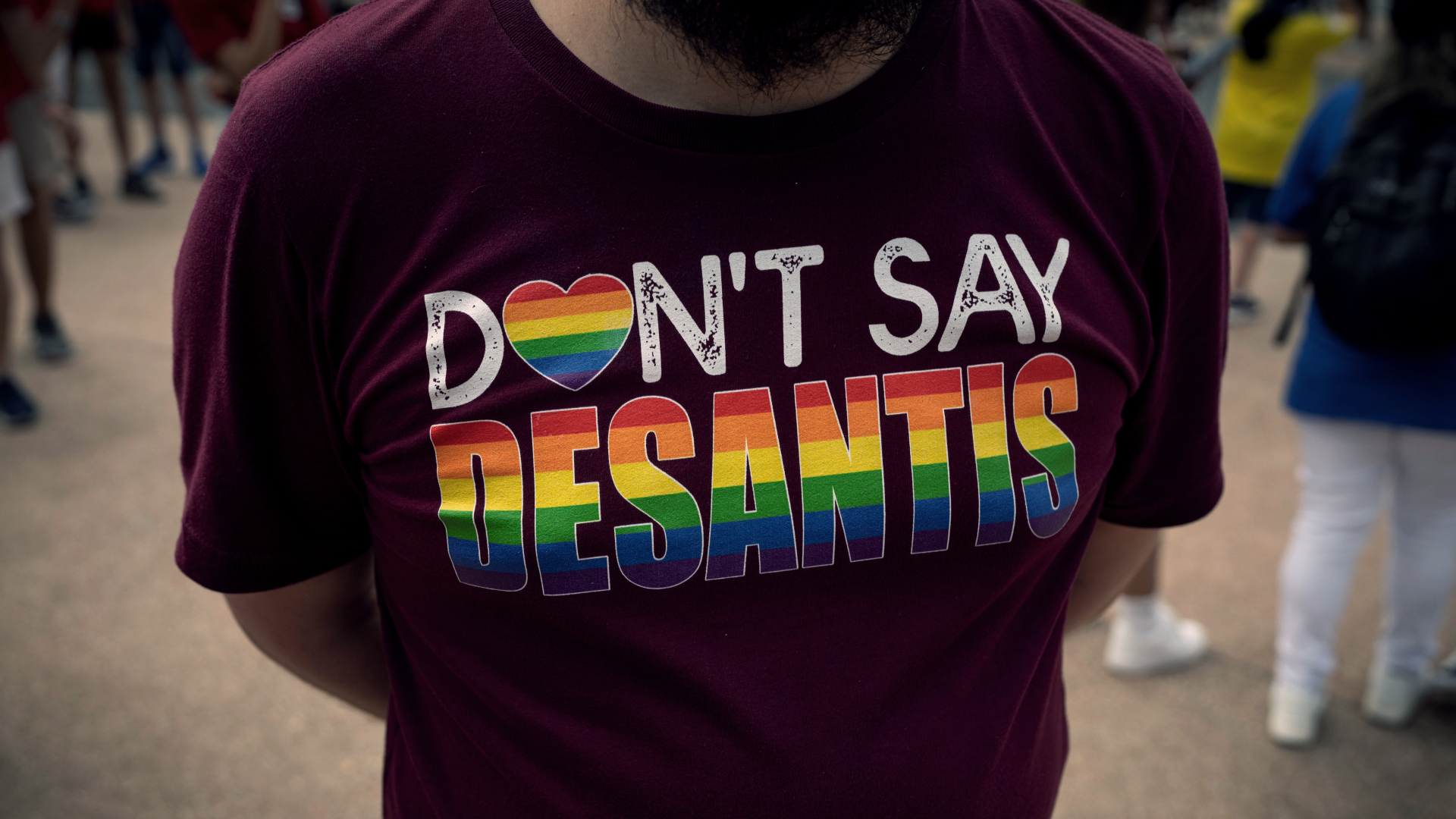

Florida teachers can 'say gay' under settlement

Florida teachers can 'say gay' under settlementspeed read The state reached a settlement with challengers of the 2022 "Don't Say Gay" education law

-

Schools are suffering from low attendance

Schools are suffering from low attendanceUnder the radar But students are suffering even more

-

The UK students taking on universities over Covid disruption

The UK students taking on universities over Covid disruptionfeature Claimants say they received poor service and felt like ‘lowest form of life in food chain’