A brief history of third parties in the US

Though none of America's third parties have won a presidential election, they have made a large impact on the country's politics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Two parties are too few for some Americans. Yes, Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris are the two major contenders for the presidency in November 2024. But many voters would like to see additional choices.

A recent poll of progressive activists found that “one in four activists knew someone who was considering a third party protest vote,” Dave Weigel said at Semafor. That’s a sign that Harris is having trouble with working class voters who have “drifted right” in recent years. And it's the latest manifestation of a longstanding American desire to shake up politics — albeit one that's always fallen short.

In just this election cycle, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. mounted his own independent bid for the presidency, as did celebrity scholar Cornel West. Both men fought battles to get on state ballots for the election, with mixed degrees of success — Arizona rejected West's efforts, while New York rebuffed several attempts by Kennedy. It proved to be hard work: Kennedy finally dropped out of the race in late August and endorsed Donald Trump.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Those are just the latest attempts to disrupt the two-party system since Democrats and Republicans emerged as the main rivalry in the mid-19th century. None of these third parties have lasted over the long term — or won a presidential election — but a few notable efforts have left their imprint on American politics and history.

American Independent Party

The notorious segregationist George Wallace formed the American Independent Party in 1968 in order to run for president. (He had failed in his effort to win the Democratic Party nomination from President Lyndon Johnson four years earlier.) Curtis LeMay, the former Air Force general who urged President Kennedy to bomb Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis, was his running mate.

Wallace didn't think he could win the presidency outright — but he did think he could game the system and play kingmaker. PBS' American Experience described the strategy in its history of the 1968 campaign: Although Wallace campaigned "as though he believed he were a viable candidate for president," the real goal was to sap enough votes from Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey, the Republican and Democratic nominees, to deny both men an electoral college victory, and thus throw the election to the House of Representatives. "There, Wallace could demand that the other candidates support him on his issues before he would deliver the presidency," said PBS.

Here's the crazy thing: it nearly worked. Wallace carried five states — Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia — and came close to Nixon in North Carolina and Tennessee. Nixon barely beat Humphrey in the national popular vote, eking out a 1% win, but claimed 301 electoral votes, which were more than needed to spoil Wallace's dream of spoiling his election. Wallace's consolation: He was the last third-party candidate to win electoral votes. He tried again in 1972 but was shot and paralyzed on the campaign trail.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Reform Party

Like the American Independent Party, the Reform Party started out as a vehicle for one man's outsized presidential ambitions. Ross Perot, the billionaire Texas businessman, had made a splashy, on-again, off-again run for president as an independent candidate in 1992 — and performed respectably, capturing nearly 19% of the popular vote. (Bill Clinton won that election, and many Republicans have long blamed Perot for spoiling George H.W. Bush's re-election in that campaign.) In 1995, he decided to make it formal, announcing the launch of the Reform Party, and predicting it would eventually replace either the Democratic Party or GOP. "One of those two parties is going to disappear," Perot said to an interviewer, "one of those special interest parties is going to melt down."

Unsurprisingly, Perot was the Reform Party's first nominee for president in 1996. But he didn't do as well as his first run — he earned just 8.4% of the popular vote. (For what it's worth, that was just about the margin of Clinton's victory over GOP nominee Bob Dole.) That was good enough that, under federal law, the Federal Election Commission in 2000 provided $12.6 million in matching funds to the party's 2000 nominee, conservative commentator Pat Buchanan. But the Reform Party has never again made quite the impact it did during Perot's first runs for the presidency.

Instead, its legacy might be best remembered for two things. In 1998, former professional wrestler Jesse "The Body" Ventura won the Minnesota governorship under the Reform Party banner — albeit with 37% of the vote. And in 2000, another celebrity businessman in the tradition of Ross Perot made a brief, aborted run for the party's presidential nomination. You might have heard of him: His name was Donald Trump.

Green Party

No discussion of modern third parties is complete, of course, without the Green Party. It originally formed in the 1980s with an emphasis on environmental justice, but it really came to prominence in 2000 when consumer crusader Ralph Nader won the party's nomination and made a bid for lefty voters who had become disenchanted with the Democratic Party's "third way" neoliberalism under Bill Clinton. Nader won just 2.74% of the vote.

That might not be worth mentioning — except, of course, that was the year George W. Bush lost the popular vote and won the electoral vote, barely. The race between Bush and Al Gore came down to Florida, which ended up infamously mired in a weeks-long haze of hanging chads amidst a recount of the votes to see who would win the state's electoral votes, and thus the presidency. Officially, Bush won the state by 537 votes, after a controversial Supreme Court ruling that stopped the recount. Nader received more than 97,000 votes in the state. And Democrats have blamed him ever since for costing the party the White House.

"Lots of factors can be blamed for such a paper-thin defeat," Bill Scher said at Real Clear Politics. But if Nader had "chosen not to embark on an obviously quixotic campaign, Al Gore would have been elected president." Nader has always denied culpability for Gore's loss. "The two-party tyranny is spoiled to the core," Nader wrote in 2016 at the Los Angeles Times. "The least-worst choices are getting worse every four years."

Forward and No Labels

The 2024 election brought several new groups into the fray. In 2022, former New Jersey Gov. Christine Todd Whitman and one-time presidential candidate Andrew Yang — who came to prominence as a Republican and Democrat, respectively — announced the formation of Forward, a centrist party designed to appeal to Americans frustrated with the country's two dominant political factions. "Some call third parties 'spoilers,'" the pair said in a Washington Post op-ed, "but the system is already spoiled."

The party didn't end up nominating a presidential candidate in 2024, but it is working on several state-level races.

It is No Labels, though — a coalition of Republicans, Democrats and independents that was formed to fight partisanship — that drew the most attention and criticism. The group was seen by critics as a means of attracting centrist votes that might otherwise go to the Democratic ticket, and thus assisting Donald Trump's election efforts. In April, though, No Labels announced it would not nominate a presidential candidate.

The idea will probably remain popular, at least in the abstract. Gallup said that 58% of Americans say a third party is needed because Republicans and Democrats "do such a poor job" of representative voter preferences. "It is unclear," Gallup said, "whether they are genuinely expressing a desire for a third option or are simply frustrated with the two existing parties."

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Who is the Hat Man? ‘Shadow people’ and sleep paralysis

Who is the Hat Man? ‘Shadow people’ and sleep paralysisIn Depth ‘Sleep demons’ have plagued our dreams throughout the centuries, but the explanation could be medical

-

Modern royal scandals from around the world

Modern royal scandals from around the worldIn Depth From Spain to the UAE, royal families have often been besieged by negative events

-

How the biggest election year in history might play out

How the biggest election year in history might play outThe Explainer Votes in world's biggest democracies, as well as its most 'despotic' and 'stressed' countries, face threats of violence and suppression

-

Will democracy survive in 2024?

Will democracy survive in 2024?Today's Big Question Elections in America and around the world will tell us 'whether democracy lives or dies'

-

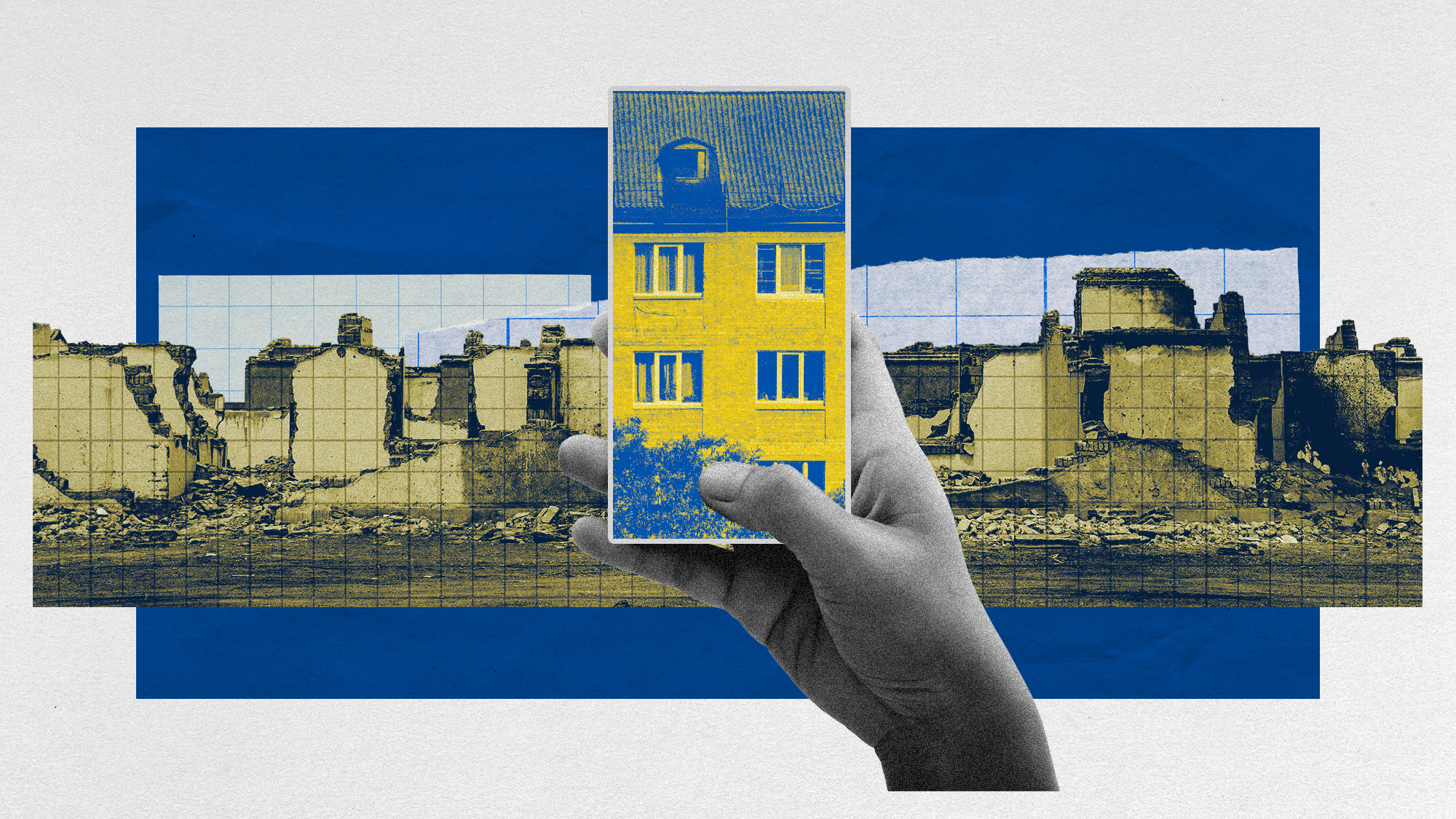

The heavy cost of rebuilding Ukraine

The heavy cost of rebuilding UkraineIn Depth Reconstructing the war-torn country will cost hundreds of billions of dollars

-

Is Biden losing Black voters?

Is Biden losing Black voters?Talking Point The prospect has Democrats nervous about 2024

-

Can Putin survive his 'catastrophic' war with Ukraine?

Can Putin survive his 'catastrophic' war with Ukraine?In Depth Putin had high hopes when he invaded Ukraine, but Russians don't traditionally reward defeat

-

Mitch McConnell defeats Rick Scott in GOP Senate leadership election

Mitch McConnell defeats Rick Scott in GOP Senate leadership electionSpeed Read