Does Ukraine have the 4 factors that go into a successful insurgency?

Lessons from history both near and far

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

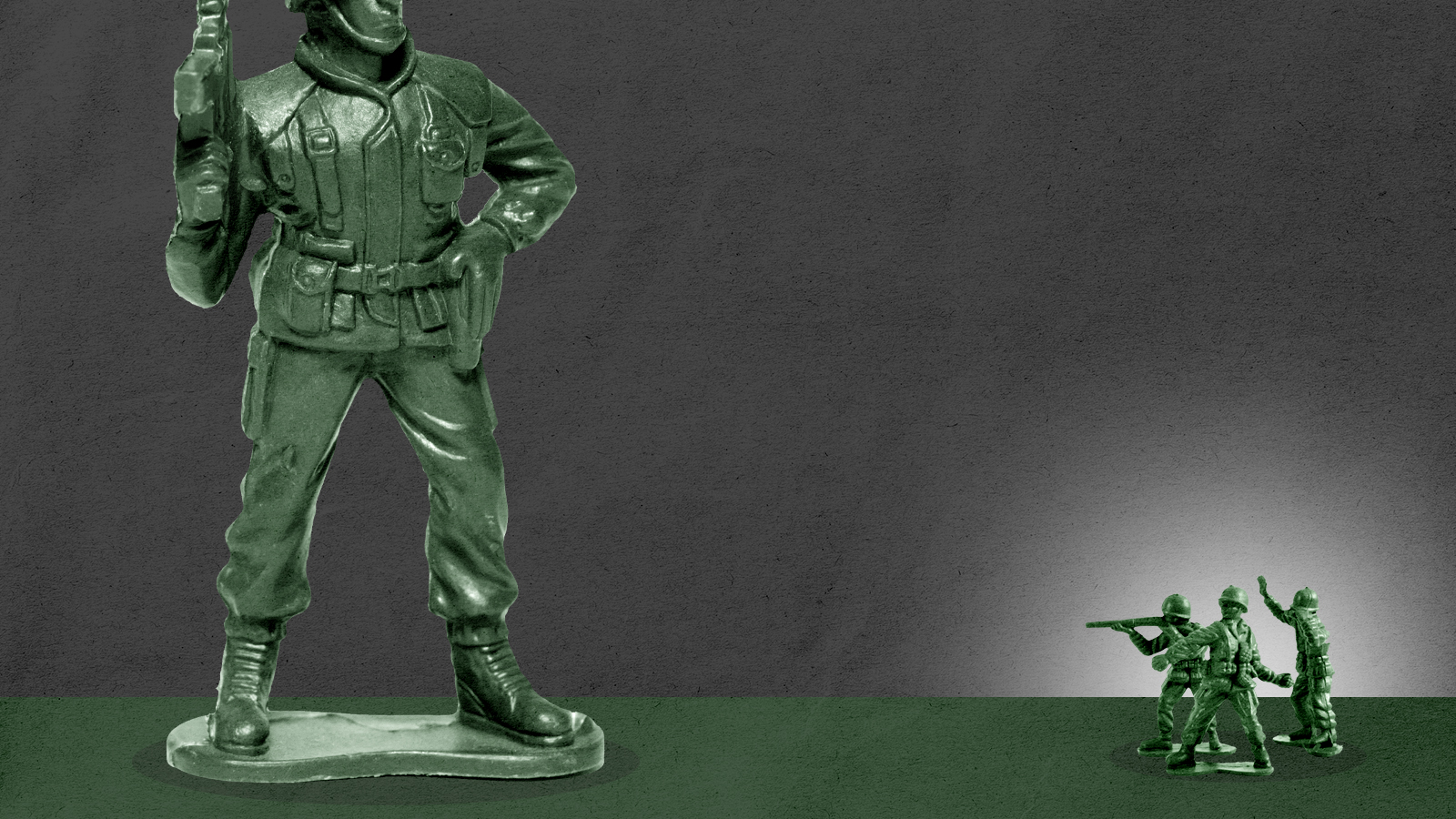

The Russian war against Ukraine has so far been fought largely between trained soldiers on both sides, and with tanks, planes, and artillery. But according to many experts, that's not where this conflict is headed. Russia's military is just too powerful, and Ukraine's conventional forces too small, despite high morale.

So, what comes next?

It seems likely that Ukrainians aren't going to surrender and allow themselves to become part of Russia, or whatever it is that Vladimir Putin has in mind. Instead, there is the possibility of an insurgency.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The dictionary defines an insurgency as "a condition of revolt against a government that is less than an organized revolution and that is not recognized as belligerency." Think of the French insurgents in World War II, whose fight against the Germans is famed and widely considered successful. But the French rebels never held territory and the actions they took led to harsh reprisals against the citizens they intended to liberate; it was the Allies landing on the beaches of Normandy and the fighting that followed, rather, that was definitive in returning France to the French, according to more recent historians.

There are many reasons why insurgencies succeed or fail, but here are four elements shared by most successful insurgencies:

Strong leadership

Some of the names are recent and familiar to us today, like Mullah Omar, leader of the Taliban in Afghanistan during most of the American war. Even though he died a few years before the final victory, the broader leadership he was a part of is in control of the country right now.

There was also strong leadership when the Soviets lost their war in Afghanistan (1979-1989), with warlords like Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum leading the way with tactical smarts, brutality, and a certain charisma.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Outside help

One thing that's hard to dispute is that successful insurgencies require outside help.

You can call what happened in Haiti in 1793 a successful slave revolt (which it was), but it was also a successful insurgency against an entrenched foe. Resources for the rebels — mostly former slaves — were extremely limited, but luckily for the fighters, the French who controlled Haiti had enemies. The British and Spanish supplied training, weapons, food, and other supplies to the insurgents, all of which had an impact on the war.

In Vietnam, likewise, the Viet Cong had an entire Ho Chi Minh Trail through the mountains and jungles to supply them, while the North Vietnamese had key material help from the Soviet Union. And in the Afghan war against the Soviets, the mujahideen — Islamic fighters backed by the United States — were famously given Stinger missiles that had a huge impact by bringing down Soviet helicopter gunships that dominated the skies.

Rough terrain

All insurgencies need such places to retreat, lick wounds, build strength, and get resupplied.

When the Arabs rose up against the Turks during World War I, one of their great advantages was being able to melt away into the deserts after attacks. They knew the ground; they knew where to find the basics they needed to survive, and they could blend into the local population. Turkish reprisals against ordinary Arabs further inflamed the situation and ended up making life harder for the Turkish overlords.

Similarly, the jungles of Vietnam were impassible and unknowable to U.S. servicemen, especially on relatively short tours in country that meant that people who learned the territory were soon rotated out. The same was true of U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan. Troops — and officers — who learned the territory and the people, were quickly replaced by people who had to start the whole process over again.

Similarly, the Chechens who fought Russia did so on their own ground. The Caucasus nation is mountainous and wild. It was only by resorting to brutal tactics that led to depopulation of some areas that the Russians were finally able to bring the region under control, and even then, they needed to put a local, brutal strongman in charge to keep order.

A foe with limits

But strong leadership alone won't get you very far, no matter how famed your commander might be. The Roman general and eventual dictator Julius Caesar conquered Gaul (modern France) over the course of about eight years, beginning in 58 B.C. During much of that time, he faced off with the wily and charismatic Vercingetorix, who made Caesar's life hell.

But eventually, despite Vercingetorix's ability to keep fractious tribes united, knowledge of the local terrain, and love of his people, he lost against Caesar's willingness to ruthlessly kill and enslave everyone who stood against him. Of the approximately 3 million people living in pre-Roman Gaul, 1 million were killed and another million were enslaved.

There is no fighting against that.

The Nazi war plan was similar. When people think of the Holocaust, they usually think of Auschwitz-Birkenau and gas chambers. Millions of Jews died that way. But more than a million others were killed by bullets. Babyn Yar, in Ukraine, is one place where it happened on an unimaginable scale — 33,000 men, women, and children.

Not only Jews were singled out for such treatment; whole villages of Christian Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, and others, were also wiped out because of the same rationale: Leave potential insurgents behind the German front lines, and they will rise up and cause trouble.

So what does all this mean for the insurgency in Ukraine?

The country has several of the advantages needed for a successful insurgency, according to history.

It has a strong leader in Volodymyr Zelensky. He is approaching legendary status in these early days of the war for both his bravery and eloquence.

It has outside help, too, coming from the U.S. and many other nations, both in terms of economic sanctions and weaponry. Weapons so far include anti-tank rockets and even fighter jets. The prospect of direct military intervention remains remote at this time.

Ukraine's territory is muddy in spring, bogging down tanks and other heavy Russian equipment. But it is not particularly mountainous, and forests only occupy 15 percent of the nation. There's also no desert to speak of, all making a successful insurgency more difficult.

Finally, there is the question of just how far the Russians are willing to go in terms of killing.

And that we simply don't know.

Jason Fields is a writer, editor, podcaster, and photographer who has worked at Reuters, The New York Times, The Associated Press, and The Washington Post. He hosts the Angry Planet podcast and is the author of the historical mystery "Death in Twilight."

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politics

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politicsIn the Spotlight President Zelenskyy’s new chief of staff, former head of military intelligence Kyrylo Budanov, is widely viewed as a potential successor