The unfortunate return of polio, explained

Why one case in New York has the nation's disease experts on high alert

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Polio is back.

The highly infectious, potentially lethal virus has been nearly eradicated through a global health campaign launched in 1988. But unlike horseshoes and hand grenades, close doesn't cut it for communicable diseases. Poliovirus was discovered over the summer in samples of wastewater in New York City and two northern suburbs, and one unvaccinated young adult in Rockland County developed paralysis in their legs due to the virus — the first known case of polio in the U.S. since 2013.

"The fact that we're finding it in wastewater tells you it's more common than people appreciate," Columbia University epidemiology professor Ian Lipkin tells Time. "We're looking at the tip of the iceberg." If we checked, "every major city in the U.S." would probably have polio in its sewage, adds Columbia virologist Vincent Racaniello. Here's what you need to know about the unwelcome return of an old public enemy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is polio, and how does it spread?

"Polio, or poliomyelitis, is a disabling and life-threatening disease caused by the poliovirus," the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention explains. It mostly affects children.

Most people infected with the highly transmissible disease exhibit mild cold or flu-like symptoms, if they have any symptoms at all, but the virus can infect a patient's spinal cord, causing meningitis, paralysis, and sometimes death. "Even children who seem to fully recover can develop new muscle pain, weakness, or paralysis as adults, 15 to 40 years later," the CDC says.

The poliovirus is spread person-to-person, in rare cases through droplets from a sneeze or cough but mostly through ingesting contaminated fecal matter. "The virus multiplies in the intestine for weeks and could spread through feces or contaminated food or water — for example, when an infected child uses the toilet, neglects washing hands, and then touches food," The New York Times explains.

Is there a cure?

No, "there is no cure for paralytic polio and no specific treatment," the CDC says.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why are health officials worried about polio now?

"Even a single case of paralytic polio represents a public health emergency in the United States," a group of public health researchers wrote in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Aug. 16, a month after New York State's Department of Health confirmed the Rockland polio case. "Based on earlier polio outbreaks," New York state health commissioner Dr. Mary Bassett said Aug. 4, "New Yorkers should know that for every one case of paralytic polio observed, there may be hundreds of other people infected."

Before polio was found in New York, Israel reported its first polio case since 1988 in March, and Britain declared the June discovery of poliovirus in London's sewers an "incident of national concern." The samples collected in London, New York, and Israel have the same genetic fingerprint, "suggesting that the virus may have been circulating undetected for about a year somewhere in the world," the Times reports. And they were all vaccine-derived virus.

Vaccines can cause polio?

The short answer is no, and certainly not the kind of vaccine exclusively used in the U.S. for the past two decades.

There are two types of polio vaccines: the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), which is injected in the arm or leg and uses a killed poliovirus to teach the body to recognize and attack the virus; and the oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), which uses a weakened virus and is administered via oral drops. Both types of vaccine are overwhelmingly safe and effective at preventing severe polio. Each has its benefits and disadvantages.

"The oral vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and can prevent infected people from spreading the virus to others, a method better suited to extinguishing outbreaks," the Times reports. "But it has one paradoxical flaw: Vaccinated children can shed the weakened virus in feces, and from there it can sometimes find its way back into people, occasionally setting off a chain of infections in communities with low immunization rates." Those rare infections are cases of vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV).

The U.S. used oral vaccines for decades, but switched exclusively to the IPV in 2000 to avoid VDPV cases. "But that doesn't prevent vaccine-derived strains from being imported by travelers from overseas, or by a U.S. resident who traveled internationally, picked up the virus from someone who had received the OPV, and brought it back home," Time notes.

Before one of those scenarios played out in Rockland County this summer, the CDC says, there were three cases of disease caused by VDPV in the U.S. since 2000, all among people with weaker immune systems or who weren't vaccinated against polio.

With very rare exceptions, if you are fully vaccinated against polio — with the IPV or OPV — you will not develop polio, not from the three wild strains or the vaccine-derived variety. If you are not fully vaccinated, you don't have that protection.

"Polio was once so feared here in the United States, but there's a reason we don't fear it anymore, and that's because of vaccines," Dr. William Moss, director of the International Vaccine Access Center at Johns Hopkins University, tells the Times. "This is one of the challenges of vaccines — you prevent a disease and it goes away, and people kind of forget about the disease or why it went away."

How can you tell if you're vaccinated?

All 50 states have longstanding requirements that children entering child care or public schools be vaccinated against polio, as well as diphtheria and tetanus, so most adults living in the U.S. "are presumed to be immune to poliovirus from previous routine childhood immunization," the CDC says.

"Still, after three years of managing their coronavirus status and taking precautions, many young people found themselves whispering aloud their unknown status on social media," the Times reports. If you aren't sure if you were vaccinated, CBS News adds, "the CDC suggests asking parents or caregivers, locating old documents from your childhood, or even asking former schools, doctors, and employers, as they may have kept a record of proof of immunization."

If you aren't vaccinated, or you didn't get all three or four doses, it's not too late. In fact, public health officials suggest you start completing your immunization regimen as soon as possible. The good news is that, except in rare situations where you will have significant exposure to the virus, "anyone who has had a complete polio vaccination series does not need a booster," Columbia's Racaniello tells Time. "Immunity to polio conferred by vaccination lasts a lifetime," for both IPV and OPV courses.

What will it take to eradicate polio?

Eradicating a communicable disease is very difficult — the world has only done it once, with smallpox. But we've come a long way with polio since Dr. Jonas Salk developed the first vaccine in 1952.

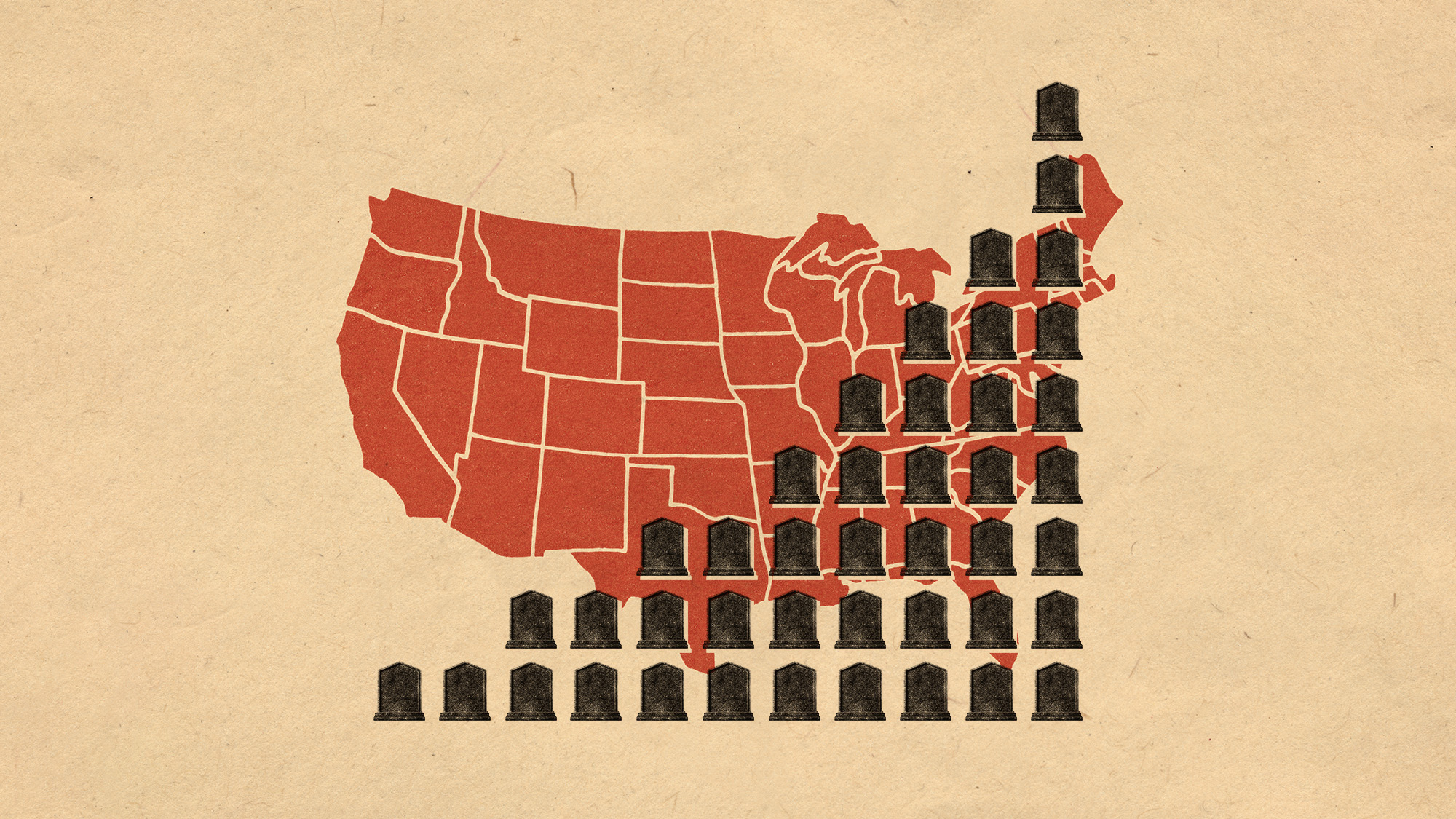

Polio first struck the United States in Vermont in 1894. "Waves of outbreaks tore through the country over the next half-century, and peaked in 1952, when nearly 60,000 children were infected and more than 3,000 died," the Times recounts. Frightened parents kept their kids home from swimming pools and movie theaters, but "after the first vaccine arrived in 1955, the number of cases dropped precipitously, and by 1979 the United States was declared polio-free."

The World Health Organization and a handful of international partners launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988 with a goal to eliminate the virus, and "despite the recent cases, the progress is unmistakable: Global cases of polio have fallen by 99 percent — from 350,000 cases of paralysis in 1988 to about 240 so far this year," the Times reports. Wild polio is endemic in only two countries — Afghanistan and Pakistan — and they appeared to be rid of polio at the beginning of 2022.

To eradicate a virus, though, it "must disappear from every part of the world and stay gone, regardless of wars, political disinterest, funding gaps, or conspiracy theories," the Times reports. In February, Malawi reported its first case in 30 years, apparently imported from Pakistan, and Pakistan then reported 14 cases of its own. Then it hit Israel, then Britain the U.S.

The current goal is to eradicate polio worldwide by 2026. That will take hard work, innovation, persistence, and an estimated $4.8 billion, the Times reports. "The moment you take your eye off the ball, you know that the virus will simply reappear," says Aidan O'Leary, the WHO's director for polio eradication. "We have to literally face down every single chain of transmission that we can identify."

The new flare-up is "a poignant and stark reminder that polio-free countries are not really polio-risk free," says Dr. Ananda Bandyopadhyay, deputy director for polio at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. And as long as the virus is anywhere on earth, it's always just "a plane ride away."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic

-

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

More adults are dying before the age of 65

More adults are dying before the age of 65Under the radar The phenomenon is more pronounced in Black and low-income populations

-

Ultra-processed America

Ultra-processed AmericaFeature Highly processed foods make up most of our diet. Is that so bad?

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures