Catholicism, George W. Bush, and the cluelessness of the religious right

Bush's theological-political vision lies in tatters. But many on the right are unable to understand why.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Once upon a time, the religious right's leading intellectuals told themselves an inspiring story. It went something like this: From the time of the Puritans all the way down to the early 1970s, American public life was decisively shaped by the moral and spiritual witness of the Protestant Mainline's leading churches: The Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Methodists, Baptists, and Episcopalians.

But then the Great Collapse began, as these venerable churches sold their souls to the counterculture, abandoned the moral and religious tenets of historical Christianity, embraced a series of increasingly left-wing and anti-American causes, and saw their numbers (and then their cultural influence) plummet. Today these churches are an intellectual and demographic shell of their former selves.

This was a potentially disastrous development, depriving America of the theologically grounded public philosophy that it needs in order to thrive. But as luck — or providence — would have it, the decline of the Mainline churches set in at the precise moment when two other monumental cultural and religious developments unfolded: The rise of a politicized form of Protestant evangelicalism and a revival of intellectual and spiritual energy in the Catholic Church under Pope John Paul II. The time was ripe for evangelicals and Catholics to come together to form a successor to the Mainline churches.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The public philosophy promulgated by this new-fangled amalgam of evangelicalism and Catholicism (with the former supplying the foot soldiers and the latter providing the ideas) would be staunchly opposed to abortion and euthanasia. It would be strongly anti-communist. It would be passionately pro-capitalist. It would favor using military force to promote democracy. And it would re-describe the United States, its history, and its form of government in providential-theological terms, with the rights espoused in the nation's founding documents declared to derive directly from medieval concepts of natural law.

Once the country (or at least a sizable majority) embraced this public philosophy — turning it into a governing philosophy — the United States would supposedly flourish as never before, protecting the unborn, unleashing economic liberty at home, defending democracy and fighting tyranny abroad, and most of all bringing the nation back to its properly Christian roots after the silly season of the 1960s.

It is exceedingly odd that Joseph Bottum has written a book — An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America — devoted to elaborating this story as if it were original to him, when in fact it is derived almost entirely from the writings of the man for whom both of us once worked: The late Fr. Richard John Neuhaus.

You see, I once edited Neuhaus' monthly magazine First Things. When I quit to write a book denouncing the ideological project outlined above, Neuhaus brought on Bottum (then the literary editor of The Weekly Standard) as my successor. When Neuhaus died in January 2009, Bottum became editor-in-chief of the magazine. (Twenty-one months later he was summarily dismissed by its governing board for reasons that have never been publicly explained.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Bottum, a published poet, is a gifted prose stylist. That gives a distinctive flair to his version of the story. But the story itself, in every detail, comes straight from the writings of Neuhaus and his small circle of ideological compatriots: Michael Novak, George Weigel, and Robert P. George foremost among them.

In Bottum's hands, no less than in the essays and books in which it was originally formulated, the story has some explanatory power. The decline of the Mainline churches is indeed a significant event in recent American cultural and political history — and one that has received insufficient attention from both scholars and intellectuals. (My colleague Michael Brendan Dougherty's thoughtful reflections on Bottum's treatment of the topic can be read here.)

But the story also obscures far more than it clarifies. For one thing, Bottum can't seem to figure out if the problems he identifies with post-Mainline America (including the absence of a unifying, overarching moral consensus and the subsequent rise in acrimonious conflict in our political culture) are a result of Protestant Christianity's inability to defend itself against an aggressive form of secularism, or if, instead, what we call secularism is actually just a desiccated form of Protestantism (hence the reference to a "post-Protestant ethic" in his subtitle). Either way, Protestant Christianity is to blame for America's problems.

Which is why Bottum (following Neuhaus and the others) turns to Catholicism for a solution.

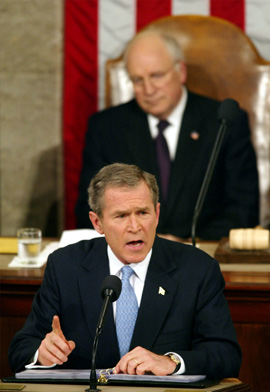

For Bottum, this was "the most purely philosophical address in the history of America's inaugurations," one that deployed "a Catholic philosophical vocabulary" rooted in natural law theory to "express a moral seriousness the nation needs."

That's one way to look at it.

Here's another: The speech was a crude expression of American parochialism and pious self-congratulation — the kind of address you'd expect from someone who believed toppling Saddam Hussein was a sufficient condition for creating a functioning democracy in Iraq, and who thinks that presidential rhetoric can rise no higher than paraphrasing the lyrics to "Onward Christian Soldiers." It was the speech of a simple-minded man leading a simple-minded administration.

The most interesting and original thing in Bottum's book is a new-found pessimism about the practical prospects for the theological-political engagement he still favors. But I would be more impressed with this darkening mood if it grew out of a realization that great political leadership involves far more than moralistic sermonizing — and that something as partisan and sectarian as a Catholicized version of the Republican Party platform could never serve as the unifying, overarching moral vision of a pluralistic liberal democracy.

Instead, we're left with vague, evasive statements about how "Catholicism as a system of thought proved too foreign" to play its appointed role as cheerleader for American exceptionalism.

Poor Joseph Bottum. Poor religious right.

They're down for the count, splayed out on the mat. And they haven't got a clue about what the hell happened.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Political cartoons for February 3

Political cartoons for February 3Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include empty seats, the worst of the worst of bunnies, and more

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJ

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJSpeed Read Ed Martin lost his title as assistant attorney general

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred