Linguistic invasion! The foreign influence of English's political and military words

It might seem like our language is under attack. But in reality, we're the ones taking linguistic prisoners

After being at something of an impasse, Egypt has had what some are calling a coup, provoking concerns that the country may be ruled by a junta or some generalissimo. It doesn't help that Mohammed Morsi seems to be incommunicado.

Did you notice? Our language about politics and warfare seems to have been invaded by French and Spanish terms! Impasse, coup, junta, generalissimo, incommunicado…

Now realistically, we have a lot of political and military words that aren't direct loans from these languages; you're more likely to hit a word that's an English modification of something from Greek (e.g., monarchy, democracy, tyranny) or Latin (e.g., candidate, constitution, republic). But we do seem to have quite a few words from French and Spanish — and, incidentally, some also from German and Russian — in our political and military language.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

French

A huge portion of English's wordstock has been taken from French, but much of it has been modified. No one would think of army as a French word, for instance, even though it comes from armée. If we talk about soldiers or marines or pilots, we don't stop to notice that these words were taken almost unchanged from French hundreds of years ago — like many other military words, and government, too. After all, England was ruled by the French for a few centuries, and the French had a profound effect on English vocabulary. Most of the words of more than one syllable in this paragraph come originally from French, for instance.

But there are a few that have been taken recently enough, and unchanged, that we still notice. They've all been borrowed from French at various times over the past four centuries, often surrounding some significant historical event involving the French.

Some were taken while the English nobility retreated to France in the mid-1600s, such as coup d'état (reappearing after the French revolution), aide-de-camp, and commandant (which came to be used more after the World Wars). Some came to us around or after the French revolution, such as esprit de corps, impasse, agent provocateur, and laissez-faire.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some, on the other hand, owe their current popular use to political writers such as Marx, notably bourgeois. Some come just from international diplomacy over the centuries, such as bureau. And some were borrowed from 20th-century politics, such as détente.

Generally, we took these words because there was a new idea, or a variation on an idea, that we got from the French and we didn't have an exact word for before. We're so used to French words, they often slip in without too much trouble — to join their long-lost cousins.

Spanish

The Spanish never conquered England, though they did send an armada against Elizabeth I in the late 1500s — with bad results.

These days, when we use a Spanish word, we tend to project ideas about Latin culture on it. We could always talk about a military ruling council, but if we say a junta it makes us think of those guys in certain Latin American countries. If you think of a generalissimo, you may think immediately of Francisco Franco, or perhaps of some Latin American military chief.

Likewise, even though the conquistadors were doing the same kinds of things many English-speaking invaders and conquerors did, we have a different attitude towards the ones we give the Spanish name. Similarly, there are outlaws, and then there are desperados. We're more mixed in our opinions of guerrillas now, but we'll still think of people like Che Guevara.

The funny thing about these words is that some of them have actually been seen in English for a long time — junta, generalissimo, and desperado since the 1600s, guerrilla and conquistador since the 1800s.

We do have a few other words that we may not even think of as Spanish: for instance, flotilla, borrowed in the 1700s; incommunicado, with us for a bit over a century; and politico, first used in the 1600s to refer to a politician, and in more recent centuries to refer more broadly to someone involved in politics.

Russian

Russian has lent us a few words for political things. Some of them, like glasnost and perestroika, have been borrowed recently to refer to things happening in Russia and really haven't been used for much else (after all, we have the words openness and reorganization to use for the same things everywhere else, but it makes us sound smart and informed to use the Russian word when talking about Russia). Some were borrowed to refer to specific things in their historical times: from Soviet times, Bolshevik and gulag; earlier, pogrom. Some show cultural stereotyping: we now sometimes use apparatchik where we could simply use bureaucrat because it has a more Soviet sound to it.

But there are at least a couple that have come to have much broader use in English. We may not even think of intelligentsia as a Russian word anymore — we've had it for well over a century now. And then there's czar. The U.S. government has a few of these. The original, of course, was a king of Russia; we now spell that tsar, a more correct transliteration. But this word is really just what the Slavic languages did with the Latin word Caesar. Go figure.

German

Even though English is related to German much more closely than it is to French and Spanish, England has not had the same kind of traffic with Germany — sure, it's gotten members of the royal family and all that, but the last time Germans came in and took over England, it was not long after AD 600, and they just brought their language, which became the one we speak now. The political and military words we have borrowed from modern German have come in almost entirely because of the two World Wars: nazi, gestapo, führer, kaiser, realpolitik, blitzkrieg, flak.

Most of those have another thing in common: that German tendency to make words by pasting together other words, or bits of other words. Nazi is from Nazionalsozialist, "National Socialist"; Gestapo is from geheime Staatspolizei, "secret state police"; Flak is from Fliegerabwehrkanone, "aircraft defense gun"; Blitzkrieg is from Blitz "lightning" and Krieg "war"; Realpolitik is from real, as in real-life and practical, and Politik, which means exactly what it looks like it means. As to the other two I mentioned, Führer is just German for "leader" and Kaiser is a German version of the Latin word Caesar (so, yeah, another tsar).

Did you notice the other thing they all have in common? All those capitals. We don't capitalize them all in English now, but in German they're all capitalized, because German capitalizes nouns. And yes, they're all nouns: words for things, not actions.

Now go back and look at all the other words I've talked about in this article. Yup. Every last one of them is a noun. We haven't borrowed too many words for actions — not in politics and not in most other areas. But when we see a concept or thing we like in another place and language, we take a souvenir word for it.

We're not being invaded. We're conducting raids and taking prisoners. True, many of our familiar English words — and, for that matter, English itself — come from invaders (German first, then Norse, then French) coming to England and staying and becoming English-ized. But these ones that are more obviously from another language — as well as the occasional one from languages other than the four above — come from going on little visits to other cultures… and bringing home captives.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

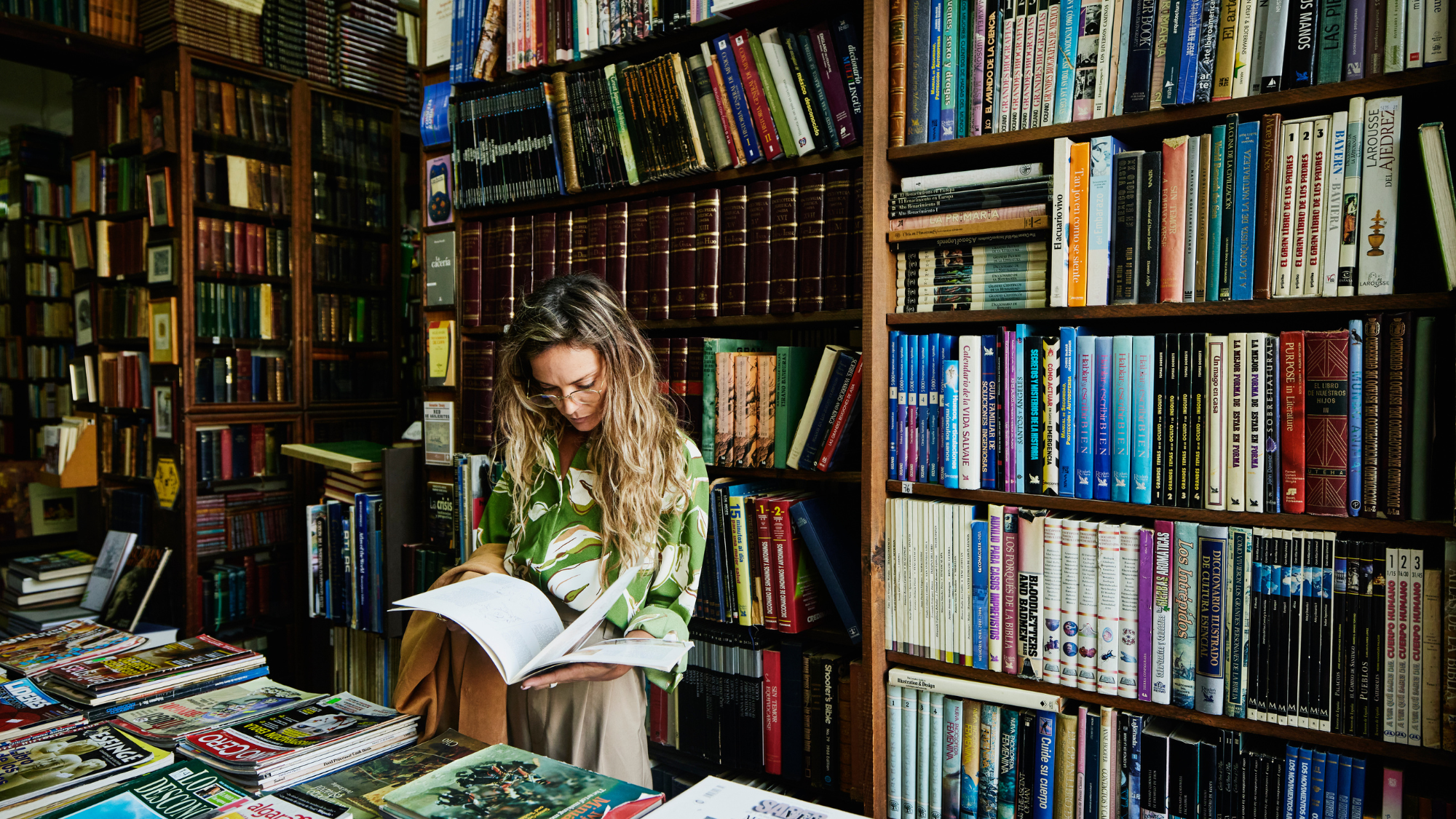

Must-see bookshops around the UK

Must-see bookshops around the UKThe Week Recommends Lose yourself in beautiful surroundings, whiling away the hours looking for a good book

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Nasa’s new dark matter map

Nasa’s new dark matter mapUnder the Radar High-resolution images may help scientists understand the ‘gravitational scaffolding into which everything else falls and is built into galaxies’

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

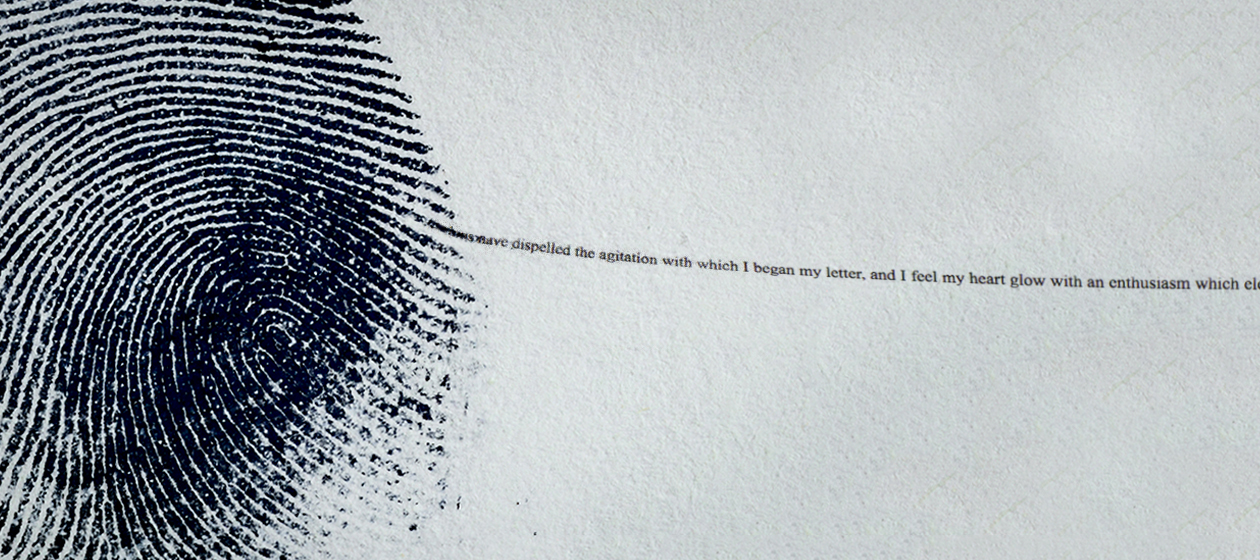

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.