The puzzling Putin-Erdogan bromance

The two presidents are palling around. Neoconservatives saw this coming ages ago.

In the span of a year, relations between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan have gone from hostile to blossoming bromance.

Indeed, it was only last November that Turkey shot down a Russian airplane doing sorties over Syria on flimsy pretenses of encroaching over its airspace, sparking a confrontation between the two nations. Thankfully, the conflict did not escalate further, but Russia adopted a confrontational stance towards Turkey and found various ways to retaliate.

My, how things change.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, Putin and Erdogan are set to have a "personal meeting" on Aug. 9. They're having good-natured chats over the phone. Russia has lifted restrictions on Turkish travelers and Putin has directed his cabinet to work on mending relations between the two countries. The two nations' soccer teams are scheduled to have a friendly match.

So what happened? It's simple: the Turkish coup attempt. In response to the failed coup, Russia published an open letter of solidarity with the Turkish government. And in the aftermath, President Erdogan launched a massive purge in the country, shutting down media and jailing scores of civil servants and teachers. In doing so, Erdogan confirmed what had become increasingly obvious: He is an authoritarian leader.

In other words, Erdogan is someone in the mold of Putin.

Like Putin, Erdogan poses as a democratically elected leader but instead enjoys personal rule, and only maintains the trappings of liberal democracy for propaganda purposes. Like Putin, Erdogan co-opts religious sentiment for his own political purposes in a country that used to be formally secular but where the old-time religion was always a vital undercurrent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Putin should be pleased; he seems to genuinely view his style of leadership as an alternative to the West's liberal democracy. Going forward, we should expect both countries to cooperate even more — and Turkey, a NATO member, to further distance itself from the West.

All of this comes as no surprise to neoconservatives like myself. But before we go any further, let me first explain what that term, which mostly gets hurled as an insult these days, refers to in the world of geopolitics.

Neoconservatives are usually contrasted with so-called realists. Realists believe in nothing but power politics: Countries will (and should) act according to their naked self-interest. Beliefs don't matter, only interests.

Neoconservatives, on the other hand, believe that both beliefs and interests should dictate foreign policy. America shouldn't just try to advance its narrow interests; it should promote human rights and democracy around the globe — with force, if necessary. Neoconservatives believe this serves America's long-term interests because democratic countries tend to be friendlier to one another — and authoritarian countries tend to band together to frustrate America.

The new Putin-Erdogan bromance is a great example. The game of power politics states that there should be no love lost between Russia and Turkey. Russia's key geopolitical objective is access to warm water and expanding its sphere of interests. Turkey is in the way of both those goals. As Russia started throwing its weight around in Syria, protecting its alliance with Bashar al-Assad and backing people Turkey didn't like, Turkey got antsy and retaliated. But then something changed, and interests and beliefs aligned.

This is the key insight of neoconservatism: Nation-states are abstractions. Countries are led by real human beings with real psyches and beliefs, and the psyches and beliefs of the leaders of nations, and the incentives they face within their internal politics, will also shape how they approach their internal politics. Today no one can imagine a war between Germany and France, not because Germany wouldn't be more powerful if it annexed Alsace-Lorraine, but because Germany is run by civilized, democratically elected people, and so is France. Both those leadership classes have devoted decades of conscious effort to creating a tight web of common interests to make war between the two unthinkable.

In a way, the distinction between realism and neoconservatism has become more academic than ever. Betting on someone acting on their own self-interest will almost never be a dumb move, and no one pretends that common sense insight can be jettisoned completely. At the same time, it's also become accepted that the unprecedented interconnectivity of the planet means countries' internal politics matter as well as their external politics.

Ideas really do have consequences. And whatever the track record of specific decisions, all American presidential administrations since Ronald Reagan have tried some sort of mix of realism and neoconservatism.

The progress of democracy makes the world more peaceful, and the progress of authoritarianism increases geopolitical risks. Putting that insight at the center of the West's dealings with the rest of the world is the path to a better world for all of us. And you can thank those dreaded neocons for that realization.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

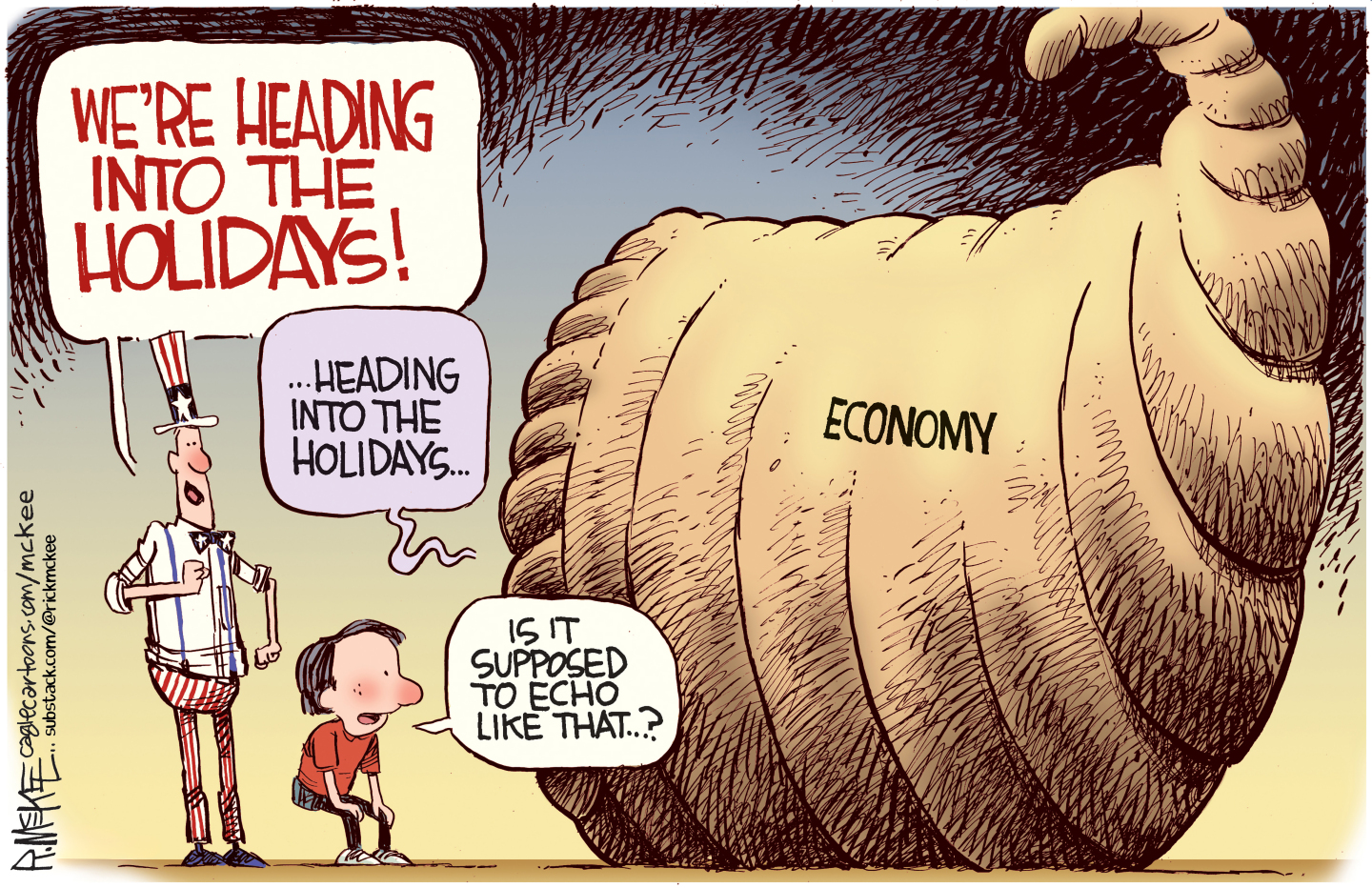

Political cartoons for November 23

Political cartoons for November 23Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include a Thanksgiving horn of plenty, the naughty list, and more

-

How will climate change affect the UK?

How will climate change affect the UK?The Explainer Met Office projections show the UK getting substantially warmer and wetter – with more extreme weather events

-

Crossword: November 23, 2025

Crossword: November 23, 2025The daily crossword from The Week

-

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump era

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump eraThe Explainer Some of Trump’s behavior has Americans being questioned

-

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threat

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threatSpeed Read Trump has claimed the country is persecuting Christians

-

Sanae Takaichi: Japan’s Iron Lady set to be the country’s first woman prime minister

Sanae Takaichi: Japan’s Iron Lady set to be the country’s first woman prime ministerIn the Spotlight Takaichi is a member of Japan’s conservative, nationalist Liberal Democratic Party

-

Russia is ‘helping China’ prepare for an invasion of Taiwan

Russia is ‘helping China’ prepare for an invasion of TaiwanIn the Spotlight Russia is reportedly allowing China access to military training

-

Interpol arrests hundreds in Africa-wide sextortion crackdown

Interpol arrests hundreds in Africa-wide sextortion crackdownIN THE SPOTLIGHT A series of stings disrupts major cybercrime operations as law enforcement estimates millions in losses from schemes designed to prey on lonely users

-

China is silently expanding its influence in American cities

China is silently expanding its influence in American citiesUnder the Radar New York City and San Francisco, among others, have reportedly been targeted

-

How China uses 'dark fleets' to circumvent trade sanctions

How China uses 'dark fleets' to circumvent trade sanctionsThe Explainer The fleets are used to smuggle goods like oil and fish

-

One year after mass protests, why are Kenyans taking to the streets again?

One year after mass protests, why are Kenyans taking to the streets again?today's big question More than 60 protesters died during demonstrations in 2024