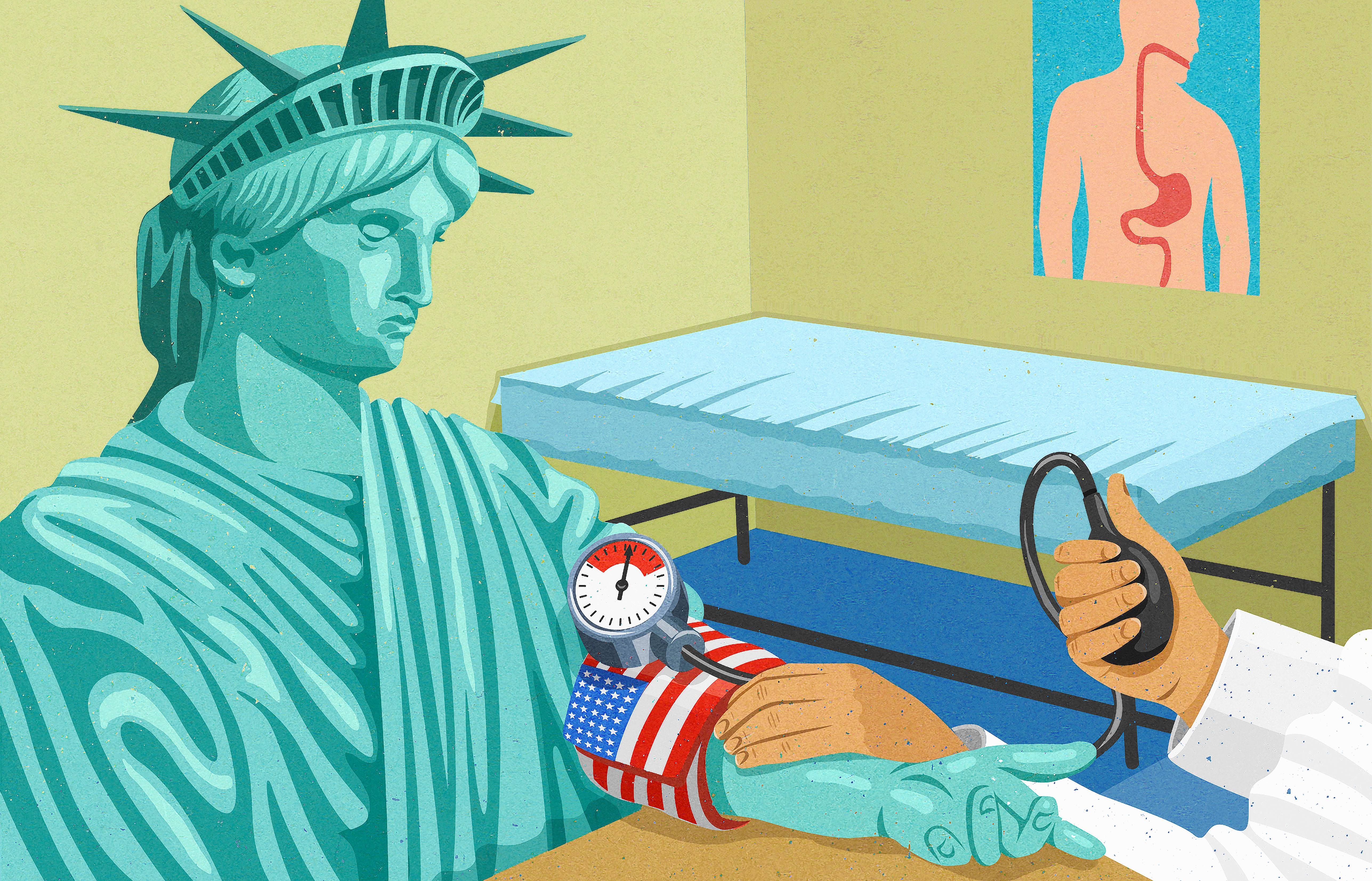

Hillary Clinton, and the sad economics of working through illness

Having to power through illness will sound awfully familiar to many Americans

It's safe to say that one word most Americans don't associate with Hillary Clinton is "average." But if anything can allow Hillary Clinton to seem like an average American, it's probably the latest controversy over her health.

Clinton had to leave a 9/11 ceremony early on Sunday after a brief fainting spell, which her campaign initially attributed to dehydration and overheating. Later, they were forced to belatedly admit Clinton had been diagnosed with pneumonia on Friday. That set off a storm of media speculation about Clinton's health, and a back-and-forth over the wisdom of the campaign's decision to stay mum about the illness.

Certainly, not acknowledging when you're ill, and insisting on just "powering through" at work, is silly and foolish. But it's also about as American as apple pie.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It should go without saying that most Americans aren't soldiering on through illness to keep Donald Trump from winning the presidency. But for them, the stakes are still quite dire. To give one example: Half of all U.S. fast food workers told a 2015 survey they've reported to work while sick because they didn't want to lose out on a paycheck.

The trouble is, American law allows for 12 weeks of unpaid leave without losing health insurance or your job. But we stand alone among advanced Western nations for having no national law that mandates paid sick leave for all workers. Plenty of employers do offer it voluntarily, but over a third of American workers don't get any paid sick leave. (The situation is even worse for paid leave to take care of family members or newborns.) There's also a big class divide here: Well-paid upper class workers are over twice as likely to get paid sick leave as low-paid Americans.

And with so many families just barely scraping by, forgoing income to recover from illness is an unaffordable risk. Roughly 60 percent of service employees and 38 percent of construction workers say they'd have to give up income to stay home during an illness. And government reporting shows about four out of every 10 workers in the private sector can't take a day off without forgoing pay.

The irony is all this comes back to bite us: When people go to work sick, they're far more likely to make others sick as well. One study this year found that flu-like illnesses (such as what Clinton has) dropped 5.5 percent on average, in seven different cities, after they passed various laws mandating some amount of paid or unpaid sick leave for workers. Not surprisingly, paid sick leave laws reduced the disease rate by more. And since about half of the workers in those cities were already lucky enough to have an employer that voluntarily gave them paid sick leave, the actual effect on influenza rates of the new laws was probably closer to a 10 percent decrease.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In fact, this is probably how Clinton herself caught her bug: A campaign source told People at least six people at the Clinton campaign's Brooklyn headquarters came down with pneumonia in the last few weeks.

Now, a big part of the controversy swirling around Clinton isn't based on the fact that she's sick, but on the fact that she hid it from the public and wasn't forthcoming. But even that reticence bears a certain resemblance to a dilemma all American workers face: That in an economy as cutthroat as ours, to acknowledge being sick is to acknowledge being weak. And to acknowledge being weak sends the subtle message that maybe it's time to step aside and let someone more vital and vigorous take over your job.

For that exact reason, many people will hide more serious medical problems — cancer and so forth — from their employer, long past when such secrecy would seem to be sensible. "The diagnosis is a crisis in itself," one oncology social worker and director of education and training for cancer care in Manhattan told The New York Times in 2005. "The next crisis is telling people," because it can force a worker to choose between protecting their job and protecting their health.

And for low-wage workers, easily disposable by employers and often faced with capricious and unpredictable schedules to begin with, there's a far greater risk of being fired even for taking off time for far more mundane medical issues.

Now, Clinton herself doesn't have a boss beyond the notoriously demanding American voter. And both she and her staff are far more economically privileged than most. But it's worth considering that sick leave as an indulgence has gone beyond an employer-enforced norm and taken on a cultural life of its own.

But the good news is that efforts to change paid sick leave in America are heating up. Laws to give all workers paid sick days are wildly popular with voters, and over the last decade a flood of new laws requiring paid sick leave for workers passed in 28 cities and five states. In just the last year, the portion of low-wage workers with paid sick leave increased from 31 percent to 40 percent.

Finally, at the national level, some lawmakers are pushing the Family Act, which would give every American worker 12 weeks of paid medical leave through a structure similar to unemployment insurance. Clinton herself has endorsed a version of this plan. And while her presidential campaign isn't a normal job, Clinton can certainly point to her own bout with pneumonia — and all the contradictory stresses it put her under — as a practical example of why laws like this are needed.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Political cartoons for January 4

Political cartoons for January 4Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a resolution to learn a new language, and new names in Hades and on battleships

-

The ultimate films of 2025 by genre

The ultimate films of 2025 by genreThe Week Recommends From comedies to thrillers, documentaries to animations, 2025 featured some unforgettable film moments

-

Political cartoons for January 3

Political cartoons for January 3Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include citizen journalists, self-reflective AI, and Donald Trump's transparency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook