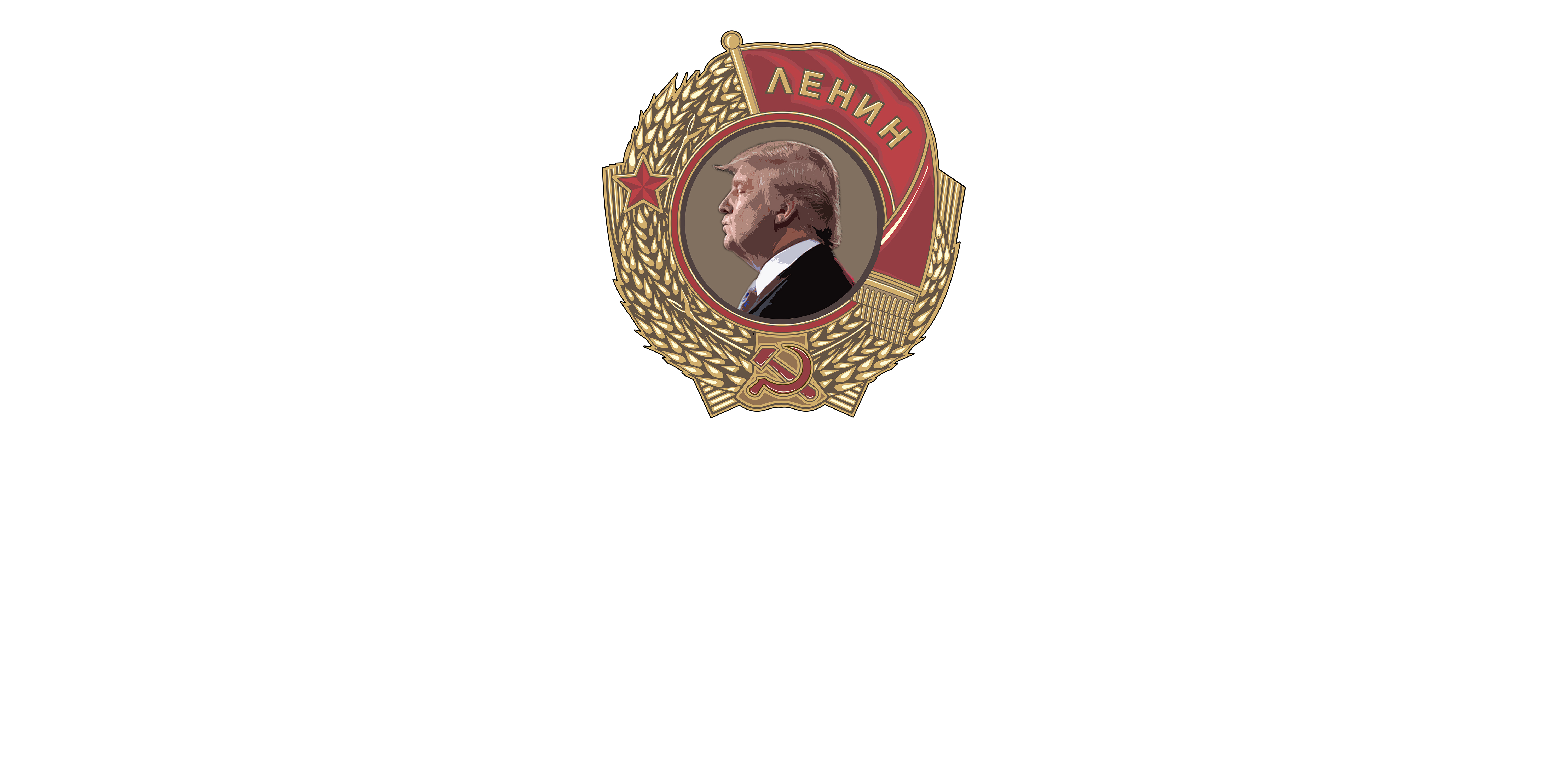

American Pravda: How Donald Trump could sovietize the media

This is how a free press dies

"Pravda" is the Russian word for "truth," but as the old Soviet joke goes, there was no truth in Pravda. For decades the newspaper was the mouthpiece of the Soviet Union's ruling Communist Party, a broadsheet filled with propaganda and false news, the adoring lapdog of Joseph Stalin and his successors. Even when it came to covering the more unsavory details of Soviet life, Pravda could "turn black into white," to borrow the phrase George Orwell used when he all but personified the publication as Squealer in Animal Farm.

In the Soviet Union, Pravda was more than a paper — it was required reading for any good comrade. "In cities and towns those who reported back on local events and those who distributed papers, Iskra, Pravda, became party organizers," PBS writes. "Readers became party members."

Although the paper's influence eventually collapsed along with the Soviet Union, it set a precedent for Russia, a nation that remains "an innovator of modern state propaganda," as the non-governmental press watchdog Freedom House writes. And despite now being in the throes of the internet era, Russian President Vladimir Putin's massive "misinformation machine" continues to promote Kremlin-friendly messages while stoking resentment of the United States and Europe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But people don't read — and believe — state-run media because they're stupid. Readers turn to state-run media because it has stories, access, and scoops that independent media doesn't by virtue of its proximity to government.

And in confusing, tumultuous times, any explanation, even a suspiciously convenient one, can feel reassuring. "Affixing officially sanctioned meanings to phenomena of daily life was not entirely a manipulative process," Jeffrey Brooks, a professor of Russian history at Johns Hopkins, writes for the Slavic Review. "This huge linguistic operation, so baffling to the outside world, was driven in part by a very human need for public explanation."

Brooks adds that "the editors and journalists of the central press … produced an image of Soviet society that was accepted among a wide circle of friendly readers who had a stake in the system and were willing to believe in a public explanation that served their interests. The image was also acknowledged by the mass of the population who had no alternative."

Russian-born investor Vitaliy Katsenelson, now based in Denver, experimented with this theory by willingly giving himself no alternative, spending a week in 2014 getting his news solely from Russian-run media. He observed that a well-oiled misinformation machine makes you doubt whatever independent voices may manage to squeak through the noise: "After watching Russian TV, you would not want to read the Western press, because you would be convinced it was lying," Katsenelson admitted. "More important, Russian TV is so potent that you would not even want to watch anything else, because you would be convinced that you were in possession of indisputable facts."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Compared with the Russian media state, the United States has long been a bastion of the independent press in an increasingly silenced world. The U.S. has actually seen an upward tick in press freedom even as the world has fallen to the lowest collective press freedom score in the past 12 years.

Yet the election of Donald Trump could prove to be a turning point for the U.S. The promotion of Breitbart's executive chairman Steve Bannon to White House chief strategist; the unprecedented request to reportedly bring Trump's son-in-law, Observer publisher Jared Kushner, to daily presidential briefings; Gawker opponent Peter Thiel's suspicious place on the transition team; and Vice President-elect Mike Pence's own dabbles in state-run media all raise concerns about the Trump administration's relationship with the press.

Most immediately concerning is Breitbart News, the alt-right publication that earlier this year endured an exodus of writers as it became increasingly clear it was an "unaffiliated media super PAC for the Trump campaign." "It will be as close as we are ever going to have — hopefully — to a state-run media enterprise," former Breitbart spokesman Kurt Bardella recently, and optimistically, told The New York Times.

The staff of Breitbart is already celebrating, too. "We're going to be the best place for news on the Trump White House," the publication's editor-in-chief, Alexander Marlow, has said, echoing the promise of exclusivity that has long drawn Russian readers to Pravda. "That is my intention and I have no reason to think that's not a fully attainable goal," Marlow added.

Breitbart has already promoted the kind of propaganda that state-run media organizations are so fond of. A map of the United States that allegedly showed Trump's Putinesque "popularity" went viral after it was published by the website (The Washington Post labeled the illustration "hilariously idiotic"):

As unbelievable as it may be, the highly manipulated map went unquestioned by many of the people who shared it, indicating how easy a pill state-run media is to swallow, especially when it reaffirms something you want to believe. "[T]he atomization of news, with articles spreading through social media, means it's sometimes hard to assess an article's accuracy: Witness the distressing spread of hoax stories on Facebook," The Atlantic points out.

In this way, however counterintuitive, the internet today actually helps amplify the Pravda effect. "Russia's propaganda works by forcing your right brain (the emotional one) to overpower your left brain (the logical one), while clogging all your logical filters," Katsenelson noticed. Or, to distill the whole process down to 2016's rather Orwellian word of the year, living in a "post-truth" world makes us prime for the tricks of state-run media. We see what we want to see.

The same concerns about Breitbart should be raised about the Observer, although the publication has been so far less obvious in its promotion of the president-elect's agenda. Yet its publisher, Trump's son-in-law Jared Kushner, could soon be privy to state secrets and briefings — or "scoops" that conveniently make the administration look good and Trump's enemies bad.

Then there is the placement of Peter Thiel on Trump's transition team. The billionaire famously bankrolled Hulk Hogan's lawsuit against Gawker, an act of revenge that financially gutted the website and ultimately resulted in its closure. Thiel's vendetta was "nothing different to governments using legal or economic leverage to shut down a media that happens to displease them," Reporters Without Borders' Gilles Wullus told the BBC.

Trump has likewise threatened to sue or otherwise destroy the free, independent media: "When they write hit pieces, we can sue them, and they can lose money," he has said, a thinly veiled euphemism for run them out of business. Trump's wife, Melania, is even protected by the very lawyer who helped take down Gawker.

Even darker methods of silencing journalists are already being whispered about: Fox News host Megyn Kelly recently told CNN's Anderson Cooper that a top executive at her network had to explain to two top Trump aides why Kelly "get[ing] killed" would be bad for the campaign.

Then there's Vice President-elect Mike Pence, who has so far proved an uncertain counterweight to Trump's skittishness with the press.

On the one hand, Pence has been lauded by the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press for being one of two lead sponsors for the Free Flow of Information Act, a bill aimed at establishing federal protections for reporters to avoid being forced to reveal confidential sources. Gerry Lanosga, an assistant professor at Indiana University's Media School, praised Pence as "a friend of the press and the First Amendment."

But the Indiana governor is also the only one on Trump's team to have already implemented a literal "state"-run publication. In January of last year, Pence announced a "taxpayer-funded news outlet that will make pre-written news stories available to Indiana media, as well as sometimes break news about his administration," IndyStar reported. It didn't go over well: The Atlantic slammed the project as being "Pravda on the Plains" and Democratic state Rep. Scott Pelath called it "an embarrassment for everybody." Ultimately Pence killed the plans, saying they were "well intentioned" but he didn't want to be mistaken for operating a "state-run news agency."

To truly establish an American Pravda would take time — time spent discrediting publications like The New York Times and The Washington Post, time spent turning viewers away from CNN and Fox News. Already, though, we have a taste of what that future might look like. Trump's first sit-down with major journalists and news anchors last Monday was likened to a "firing squad." The participants went into the meeting believing they would discuss "the access they would get to the Trump administration, but instead they got a Trump-style dressing down," with the president-elect calling the "media dishonest, deceitful liars" and picking out certain attendees for abuse.

Under President Trump, daily White House press briefings, a tradition but not a legal requirement, could become occasional, or even rare or nonexistent. Trump's concerning treatment of the press from his campaign days could also return with startling consequences, including blacklists of unfriendly publications or journalists who ask the wrong kinds of questions. Other media organizations could find themselves scrambling for access to the White House and agreeing to cover whatever show the administration decides to put on.

If this happens, Americans' best hope for learning what is happening within their own capital could be through the foreign press. When a photo of Ivanka Trump sitting in on a meeting with her father and the president of Japan went viral, it was because the image was shared by Japan's own press, as the United States' core had not been invited to the talk. Other recent revelations about the incoming administration have come from The Asashi Shimbun and Indian journalist Devendra Jain's Twitter account.

In the meantime, there is little question that Breitbart is already waiting for its chance to step into the role of Trump TV. "Breitbart will continue to be what it has been during the campaign — it was just a propaganda arm for Donald Trump," Bardella predicted to The Associated Press. "This is as close as we're ever going to be to having a state-sponsored media entity that will effectively be operating out of the West Wing."

Thousands of Americans are already fighting back. In the seven days after the election, The New York Times saw subscriptions skyrocket by 41,000, the "largest one-week subscription increase since ... 2011." Additionally, The Wall Street Journal watched subscription rates triple the normal average for a Wednesday, The New Yorker recorded gains of 10,000 new subscribers, and Mother Jones sold 10 times their average number of subscriptions on the day after the election.

In Russian, there is an idiom that might describe this: You cannot hide an awl in a sack. Murder will out. Time discloses the truth.

And in America, we can only hope that truth will keep us free.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

Why is the Pentagon taking over the military’s independent newspaper?

Why is the Pentagon taking over the military’s independent newspaper?Today’s Big Question Stars and Stripes is published by the Defense Department but is editorially independent

-

How Mars influences Earth’s climate

How Mars influences Earth’s climateThe explainer A pull in the right direction

-

‘The science is clear’

‘The science is clear’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred