Donald Trump is already picking winners and losers in business. Good.

It's time America got over its skepticism of industrial policy

Back in early 2016, an appliance manufacturer named Carrier decided to move 1,400 jobs from its plant in Indiana to Mexico. Then Donald Trump happened.

Looking to make good on Trump's promises to restore American jobs and manufacturing, the incoming administration started talking with Carrier soon after the election. On Tuesday, the president-elect and Carrier struck a deal to keep "close to 1,000 jobs" in Indiana.

Now, the deal might owe more to tax sweeteners offered by Indiana's state government, where Vice-President-Elect Mike Pence is governor. And Carrier and its parent company may have just decided the savings from Mexican labor weren't worth possibly pissing off the new administration.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what's really significant isn't how the deal went down. It's that Trump was smart enough to claim credit for the outcome.

What Trump was implicitly calling for in his campaign, and what he implicitly engaged in by sticking his nose into Carrier's business, is industrial policy. That's where the government deliberately sets out to shape the economy: to create jobs, raise wages, protect and promote certain industries, etc.

There was a time in the aftermath of World War II when it was broadly accepted that industrial policy was good and proper. That changed with the post-Reagan era of U.S. politics. Mainstream economics concluded the competitive free market was a better decision-maker than government: Industrial policy might make Americans happy by protecting their jobs and saving their towns, but it would also make the economy less efficient and slower to grow.

Ideological principle was also involved: In a free capitalist society, owners of businesses and capital shouldn't have to answer to government for their decisions, and shouldn't have to fear policy retaliation. (A big reason Carrier and their parent company buckled to Trump, for example, seems to be worries they'd get slapped with tariffs or denied government contracts or some such if they didn't.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The knee-jerk ubiquity with which politicians rail against government "picking winners and losers" is a testament to how much skepticism of industrial policy has triumphed.

But the victory over industrial policy was ephemeral and destructive.

First off, politics is still politics. So industrial policy still happens, but just on a "pork barrel" basis, changing from industry to industry and locality to locality. Mainstream economic skepticism didn't kill off industrial policy, it just made it scattershot and incoherent.

It also made industrial policy far more pro-corporate. The U.S. government could use the sticks of higher taxes, tariffs, and regulation, or even the brute force of its own spending power to build up certain industries. But mainstream economics pooh-poohs this approach. So instead industrial policy defaults to carrots: tax breaks and de-regulation that entice businesses to put jobs and investments in certain places. That drives up inequality, makes it harder to pay for social programs, and gives those businesses more freedom to exploit the public. This practice is especially rife at the state level, where governments routinely offer tax breaks and such for companies to relocate within their own borders.

But mainly, skepticism of industrial policy created a world where many Americans feel like the government's attitude toward their lives, families, and towns is benign neglect. And of course, once we abandoned industrial policy, GDP growth still slowed down, wages stagnated, unemployment became a much bigger problem, and small towns and the countryside began to die economically.

All of which is a big part of why Trump won.

That's not to say the president-elect's approach is perfect, though. Far from it.

Rather than articulate a viable set of industrial policies, Trump seems to act like a TV showman: Bully a particular company or slap a tariff on them to win the next news cycle. Trump has also made it painfully clear he's going to give the Republicans in Congress everything they want when it comes to cutting government spending, slashing federal employment, and giving tax breaks to the wealthy. So what industrial policy we'll get under a Trump administration will mostly be a continuation of the bloodless pro-corporate version, only with a few more semi-random flourishes.

But a much more robust, ambitious, and coherent set of national industrial policies would serve American workers well — especially the most vulnerable, like the poor, the working classes, female service workers, and minorities. A good place to start would be countervailing currency intervention to narrow the trade deficit, plus subsidies and tariffs to protect sectors like manufacturing from being undercut further by international competition. (See Norway and its butter industry for a good example.) To go even bolder, the government should wield its incredible spending power to just hire workers and foster industries directly. From green energy to infrastructure, the country's needs are wide-ranging.

Ultimately, everyone who opposes Trump needs to get back to the positive and confident assertion that a well-thought out and coherent industrial policy is good: That economic efficiency, while valuable, should play second fiddle to protecting livelihoods and communities. And that the decisions of owners and investors, which affect so many lives, should be answerable in some form to democratic accountability.

Otherwise voters will just settle for Trump's scattershot, strongman version.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

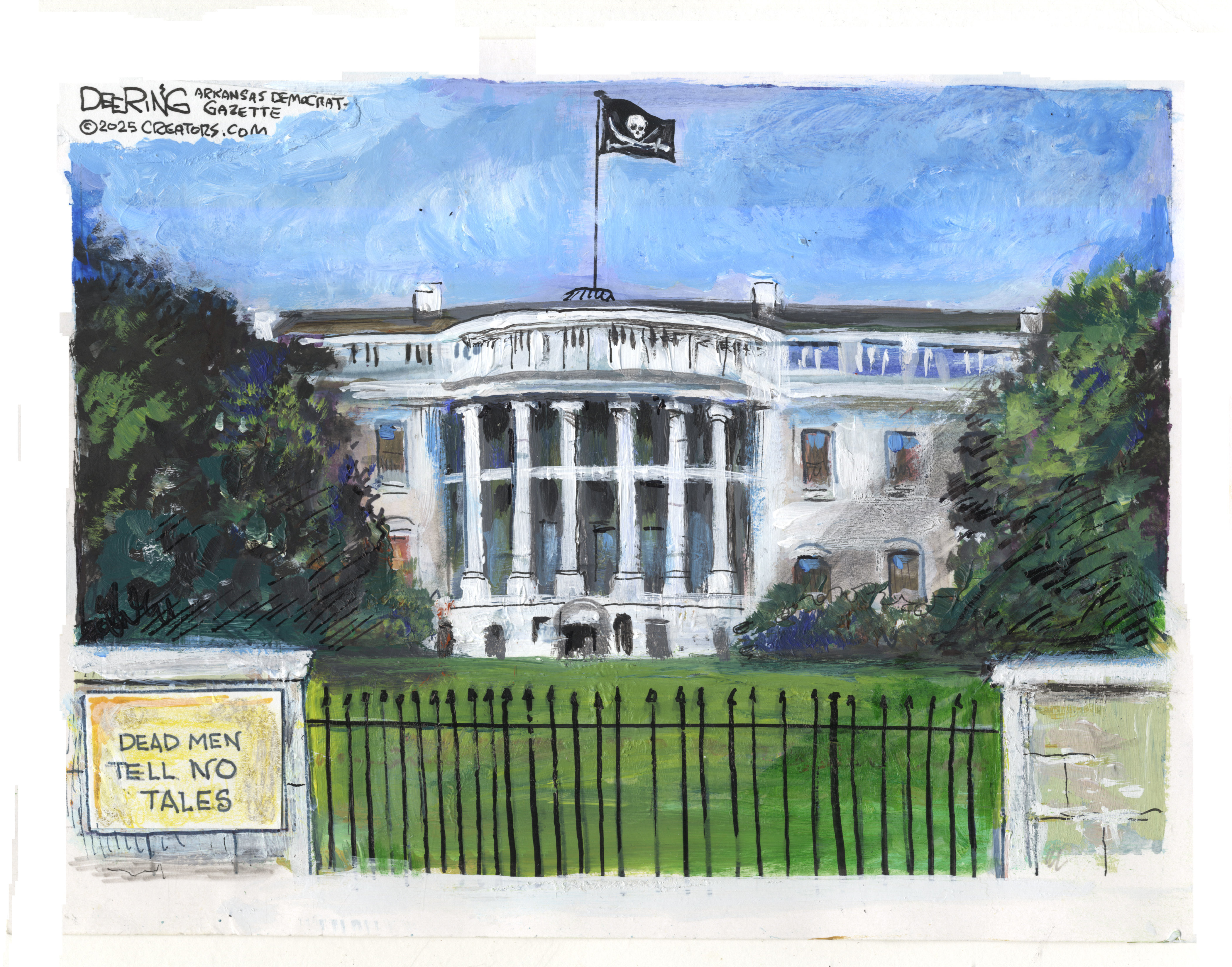

Political cartoons for December 14

Political cartoons for December 14Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a new White House flag, Venezuela negotiations, and more

-

Heavenly spectacle in the wilds of Canada

Heavenly spectacle in the wilds of CanadaThe Week Recommends ‘Mind-bending’ outpost for spotting animals – and the northern lights

-

Facial recognition: a revolution in policing

Facial recognition: a revolution in policingTalking Point All 43 police forces in England and Wales are set to be granted access, with those against calling for increasing safeguards on the technology

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration