Donald Trump's presidency is upon us. But who will President Trump be?

History can help us place the president-elect in context

What kind of president will Donald Trump be?

Of the countless essays and columns that have been penned over the past few months on Donald Trump's norm-shredding campaign, his "illegitimate" victory, his controversial Cabinet picks and staffing choices, and his Russophilia and pressophobia, just a tiny handful have offered insights that are likely to contribute in any enduring way to our understanding of the extraordinary events we've all just lived through — or that we're about to live through in Trump's actual presidency.

Political theorist and prominent left-wing intellectual Corey Robin, however, has written one of the most illuminating pieces yet about understanding what sort of president Trump will be. In "The Politics Trump Makes," Robin invokes and deploys the theories of political scientist Stephen Skowronek to place the disruptive president-elect in historical context — and to ask how disruptive he really is or will prove to be. The result is one of the most fruitful and level-headed pieces of analysis to appear in the weeks since Trump's implausible victory. It should be required reading for anyone trying to acquire and maintain their bearings through the political storms that await us.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Skowronek claimed that the character of a presidency is primarily a function of how the president positions himself in relation to the "regime" that prevails when he takes office. As Robin explains, regimes are "deep and intractable structures of interest and belief, setting out the boundaries of action, shaping our sense of the possible, over a period of decades." A president can align himself with the prevailing regime or oppose it; and the regime itself can be either weak or strong.

Those two factors determine what kind of president we get. Does he break from a past regime and found a new one, like Abraham Lincoln, FDR, and Ronald Reagan? Then he's a reconstructive president.

Or does the president merely work within and deepen the existing regime? In that case, like Lyndon Johnson expanding FDR's New Deal regime or George W. Bush building on Reagan's anti-government regime, the president engages in articulation.

Then there are preemptive presidents who oppose the regnant regime but lack the power to dislodge it. Think of Dwight Eisenhower or Richard Nixon going along with or even expanding on the New Deal regime, or Bill Clinton and Barack Obama fighting against but ultimately accepting the limitations imposed by the still-vital regime of Reaganism.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Finally, we come to disjunctive presidents — those who attain the nation's highest office just as a longstanding regime is beginning to crumble and spend their presidencies desperately mixing elements of the old regime with discordant proposals that don't quite fit and may become important aspects of a new regime once a reconstructive president gets elected. Think of Franklin Pierce's counter-productive efforts to diminish tensions over slavery — tension that finally erupted into violence with Lincoln's election. Or Herbert Hoover's halting response to the Great Depression on the eve of the New Deal. Or Jimmy Carter's somewhat hapless mixture of hostility toward and support for key elements of the regime that had defined the contours of American politics since 1933 — elements that Reagan would forcefully challenge and dislodge just a few years later.

Carter is especially pertinent for Robin's analysis of Trump because he is the most recent example of a disjunctive president, and because his unstable mixture of liberal orthodoxy (starting the departments of education and energy; spearheading efforts at energy conservation; advocating for a consumer protection agency) and heterodoxy (deregulating the banking and transportation industries; increasing military spending while cutting social spending; nominating Paul Volcker to the Fed) seem to resemble some of Trump's ideological incoherence. In the end, Carter, "like Herbert Hoover a half-century before him," ended up as "the last man standing, the poor schmuck who came into office to nudge his party away from its commitment to a weak regime, only to be deserted by his party and tarred by his opponents as that regime's most orthodox defender."

The question for Robin, as for the rest of us, is whether this is likely to be Trump's fate as well. Will he prove to be a disjunctive president who incoherently doubles down on supply-side tax cuts for the rich while also promising to defend the interests of the working class? Will he favor a health insurance plan that covers everyone while also vowing to support the much narrower market-based bill that is likely to emerge from the Republican Congress? Will he suggest that NATO is obsolete while his own nominee for defense secretary takes the opposite position?

If Trump's entire presidency amounts to a series of performative contradictions over domestic and foreign policy, it will be a strong indication that he's following in Carter's footsteps in attempting to hold a crumbling regime together while gesturing in the direction of a new regime he's incapable of founding and consolidating for himself.

That would leave the work of reconstruction — the forging of a new regime — for Trump's successor.

Robin has little to say, in this essay at least, about what might follow a disjunctive Trump presidency. His reticence is wise, since (as he notes) even presidents who are weak and disliked have "considerable resources and powers — some quite violent and coercive — at their disposal." That, plus unpredictable economic and international events, can make long-term political predictions pointless.

Yet those familiar with Robin's writing can safely assume that his hopes lie with a resurgent left. (He was a passionate Sanders supporter and savage Clinton critic throughout the 2016 campaign.) Skowronek's schema provides at least some tentative support for such hopes. The disjunctive presidency of Democrat Franklin Pierce was followed (after four years of tense placeholding by Democrat James Buchanan) by a reconstructive president (Lincoln) at the head of a whole new political configuration, the Republican Party. The transition from disjunction to reconstruction was likewise accompanied by a change of parties in 1933 and 1981.

Might the Democrats nominate a candidate in 2020 or 2024 who forges a new regime for the first time in four decades by jettisoning neoliberal centrism and building on Trump's selective expressions of solidarity with the working class, openness to a single-payer health-care system, hostility to free trade, support for industrial policy, and skepticism of foreign entanglements?

That's certainly one possible future — one that Corey Robin's thoughtful essay has prepared us to ponder (and perhaps even to begin working toward).

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 lovely barn homes

6 lovely barn homesFeature Featuring a New Jersey homestead on 63 acres and California property with a silo watchtower

-

Film reviews: ‘Marty Supreme’ and ‘Is This Thing On?’

Film reviews: ‘Marty Supreme’ and ‘Is This Thing On?’Feature A born grifter chases his table tennis dreams and a dad turns to stand-up to fight off heartbreak

-

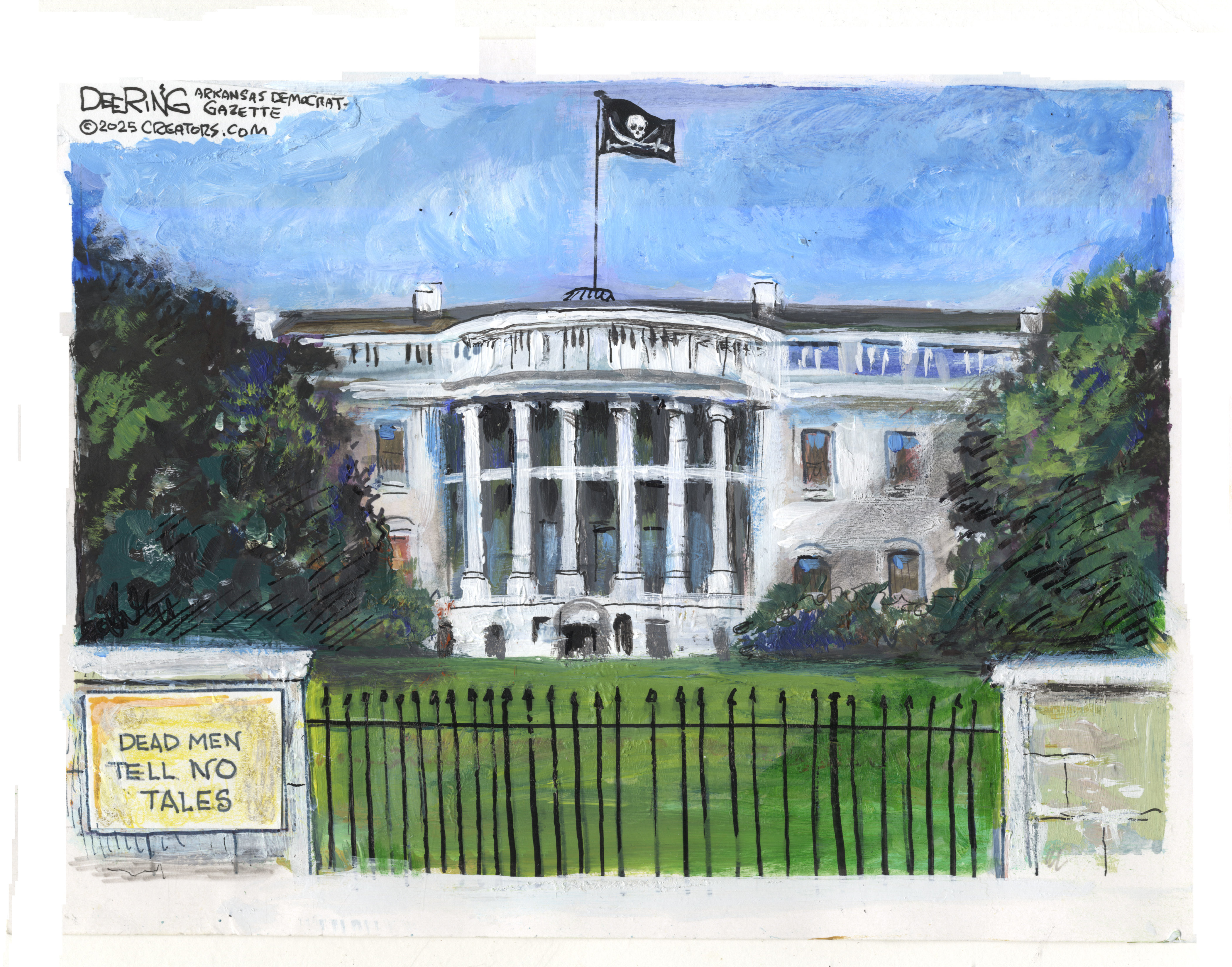

Political cartoons for December 14

Political cartoons for December 14Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a new White House flag, Venezuela negotiations, and more

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration