Trump and the revenge of Biblical literalists

Biblical literalists have given America the most factually relativist president ever

On March 1, President Trump made a quiet sort of history. Forty-one days into his presidency, according to The Washington Post's fact-checkers, he went his first 24 hours without making a false or misleading claim. Three days later, of course, Trump tweeted out an unsubstantiated accusation that his predecessor, former President Barack Obama, had ordered his Trump Tower phones wiretapped, setting off a domestic and then international conflagration.

Not many Republicans are willing to go to bat for Trump on this one. But Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.), the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee and a member of Trump's presidential transition team, did find one way to side with Trump, recently reminding reporters that the 70-year-old president "is a neophyte in politics" and chastising them: "I think a lot of the things that he says, you guys sometimes take literally." (If you did take Trump "literally," Nunes added a few days later, "clearly the president was wrong.")

This is a common Trumpian critique of the U.S. media, a formulation credited first to astute conservative reporter Salena Zito, who said of Trump in September: "When he makes claims like this, the press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally." My colleague Paul Waldman points out that since Trump is now president, literally trying to do many of the very things he was promising in September, it would be foolish not to take him both literally and seriously.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what about those Trump supporters who apparently took him seriously but not literally? Aren't they bothered that Mexico won't pay for Trump's border wall, as Trump repeatedly promised, or that it won't actually be a solid, 50-foot-high barrier, if it gets completed at all? Don't they care that the first day of the Trump presidency was tied up in lying about the size of his inaugural crowd, that his health-care plan won't cover everybody, and that he frequently and falsely paints his Electoral College victory as historically large?

Didn't they realize they were voting for a man who had more "pants on fire" than a bonfire at a frat house?

Trump is what we might call a factual relativist, choosing to promote "facts" he believes to be true — Stephen Colbert's "truthiness" as an article of faith — and ignoring or denying the facts he doesn't like. Even in a profession like politics where facts are often selectively bent to fit policy or politics, Trump stands in a league of his own.

If you're the type of person who would, say, march in a parade to affirm the need for science, factual literalism — expecting facts to be true and verifiable — may seem a self-evident value. But plenty of Americans are Biblical literalists — they believe that most everything from the Book of Genesis to St. Paul's epistles is true, with the Bible being the proof, even if scientific "facts" disagree — and there's good reason to believe a sizable majority of those voters picked Trump.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

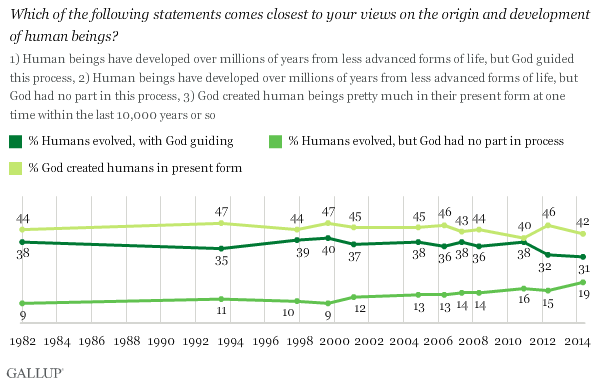

According to a 2014 Gallup poll, 42 percent of American adults "believe that God created humans in their present form 10,000 years ago," a percentage Gallup says has changed little over the past three decades, fluctuating between 40 percent and 47 percent since 1982, when Gallup began asking the question. "These Americans tend to be highly religious," Gallup said, and "also tend to have lower education levels."

Pew found a slightly smaller number of creationists in its 2013 survey, with 33 percent agreeing that "humans and other living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time," but also dug deeper. Some 64 percent of white evangelical Protestants said they believed in creationism, as did 48 percent of Republicans — a number that actually grew from 2009, when 39 percent of Republicans said they believed humans didn't evolve.

Trump, unsurprisingly, won 88 percent of Republican voters. He also won 80 percent of white evangelical or born-again Protestants, plus 54 percent of Mormons, 50 percent of Catholics, and 54 percent of other Christians, according to exit polls. And Trump won among voters without a college education by 8 percentage points — and a gaping 39 points if you just look at non-college-educated white voters. Education level was more predictive of vote than income.

So how did a vulgar, thrice-married, proudly greedy, once-socially-liberal, wealthy New Yorker who admitted to groping women and serial adultery win over religious conservatives?

Mugambi Jouet, a fellow at Stanford Law School, argues at The New Republic that "Trump and his evangelical supporters think alike in more ways than people realize," and that his factual relativism is actually a bonus.

Trump is not an evangelical, yet he too routinely defies rational thought and is unabashedly skeptical of education. While there are numerous reasons behind Trump's political success, these circumstances shed additional light on why evangelicals have been among the citizens most receptive to Trump's systematic misinformation. Evangelicals are not only heavily represented among creationists, but also among citizens who perceive climate change as a "hoax," accept calculated falsehoods about the evils of "socialized medicine," and think that Obama is a covert Muslim. [The New Republic]

But there may be a simpler explanation than Jouet's hypothesis that "anti-intellectual, anti-rational, black-and-white, and authoritarian mindsets" bind evangelicals and Trump.

Nobody likes being the unpopular kid.

Most people know this because at some time or another, most of us have been the outsider. And as my colleague Damon Linker points out, many Christian conservatives today keenly feel that they are being disrespected and disenfranchised by the moral relativists — those who believe that nobody holds a lock on what is right and wrong (you might call it "alternative moralities"), typically people who have faith in verifiable facts, the intellectual elite. You might look at the 2016 election as the Biblical literalists' revenge on those sneering factual literalists.

And if those factual literalists are contemplating a response, they would be wise to keep in mind that nobody appreciates having their core beliefs and values belittled or scorned, regardless of creed or political persuasion. The last time Democrats won control of Congress, in 2006, they had launched a concerted effort to reach out to religious voters — and the party started losing Congress again in 2010, when the Democratic National Committee's faith program had shrunk from seven staffers in 2008 to one, "who was also charged with African-American outreach — a throwback to the days when Democratic faith outreach meant showing up at black churches," noted Tiffany Stanley at The New Republic.

This shouldn't be a surprise, really — 89 percent of Americans tell Gallup they believe in God, and 77 percent say they believe in angels. Also, 79 percent of U.S. adults tell Pew that they believe in miracles — and if your instinct is to laugh at them or demand factual evidence, well, look who's in the White House.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Find art, beautiful parks and bright pink soup in Vilnius

Find art, beautiful parks and bright pink soup in VilniusThe Week Recommends The city offers the best of a European capital

-

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrum

Greenland: The lasting damage of Trump’s tantrumFeature His desire for Greenland has seemingly faded away

-

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photo

Minneapolis: The power of a boy’s photoFeature An image of Liam Conejo Ramos being detained lit up social media

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred