Against the Great Rethinking about Trump

Plenty of pernicious threats persist

For almost the entirety of President Trump's first year in office, the lion's share of his critics have treated him not just as a flawed or ill-prepared president, but as a fundamental threat to democratic government in the United States.

A year in, however, this unified front of Maximum Emergency is crumbling under the weight of second thoughts. Not only is Trump's polling ticking upward, with his approval rating recently breaking 40 percent for the first time since last May in FiveThirtyEight's aggregation of polls, but commentators from across the political spectrum have begun to pull back from the dire warnings that have characterized so much analysis of the president since his implausible victory 14 months ago.

Conservative pundit Mollie Hemingway was once a Trump skeptic, then became a leading anti-anti-Trump pundit, and now openly embraces the president on the grounds that, despite his ill-tempered tweeting, he's advancing a conservative governing agenda on several fronts. Center-right columnist Ross Douthat has never wavered in his opposition to Trump, but the fears that led him last May to call for Trump's removal from office under the 25th Amendment have faded. Now Douthat tells us the Trump presidency is more farce than tragedy, with an array of institutions hemming him in on all sides, allowing him to play-act the role of a tyrant on Twitter while the mostly normal work of government goes on around him.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Meanwhile, from the left, historian Corey Robin points out that centrist rhetoric about the nascent authoritarianism of the Trump administration isn't reflected in the actions of Democratic politicians, who have so far failed to propose any concrete measures to stand against the supposedly imminent end of democracy in America.

All of these writers have a point. Trump is governing far more like a traditional Republican than one might have predicted a year ago. The institutions of government are keeping him on a very tight leash. The apocalyptic political rhetoric of the "Resistance" does seem wildly out of proportion to what Democrats are doing to stand against the president.

But none of that diminishes the very real danger that Trump poses to American democracy. It's just that the nature of the threat may be somewhat different and more complex than some of us anticipated in the early days of the administration.

Trump is not poised to overthrow liberal democracy in the United States. But his unhinged dictatorial behavior is contributing to longer-term anti-democratic trends that portend bad things for the future of American self-government.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All of the reevaluations of the Trump administration begin from the observation that the president's freedom of movement is limited by the institutions in which his office is embedded. He's been unable to break seriously from Republican Party consensus on most issues, at least so far. (No gutted trade agreements. No major infrastructure bill. No funding for the border wall.) He's so far been equally unable to depart in significant ways from policy positions that define the conventional wisdom in Washington. (No pivot to Russia. No withdrawal from NATO. No dramatic cuts in immigration rates.)

On one level, this is a very good thing: An impetuous and ill-informed president who lost the popular vote by 3 million can't single-handedly make radical changes in the long-term policy priorities of the nation. The president is being treated somewhat like an invading virus who's being constantly attacked by antibodies meant to defend the political system as it's evolved to this point.

But on another level, there’s something deeply troubling about this dynamic. One reason why Trump rose to the top of the pack in the GOP primary field in 2016 is because a plurality of Republican voters wanted a more dramatic change of direction than the party establishment was willing to give them. Only Trump took a strong stand against immigration. Only Trump called the Iraq War a "disaster." Only Trump spoke to the economic and cultural struggles of the Republican base under Republican and Democratic administrations going back decades.

In this as in much else, Trump needs to be viewed in global context, as the American analogue to the populist and nationalist parties and movements that have been gaining ground in such European countries as Germany, Hungary, Poland, Austria, and the Czech Republic. In all of these places, voters are rising up in anger and frustration against supposedly representative institutions that appear to actively resist adjusting course in response to changes in public opinion — as if those who populate these institutions have preemptively decided that certain course adjustments are fundamentally unacceptable or illegitimate.

We saw a minor version of this institutional resistance to change during the Obama administration, when the president set out to reach a nuclear deal with the government of Iran. Because the administration was competently run, the president eventually got his way — but he did so over relentless opposition from the foreign policy establishment in Washington and the many media outlets that defer to its expertise (some of which the administration worked very hard to manipulate into going along with the change).

Because Trump is so temperamentally ill-suited to the presidency and lacks the policy knowledge to push intelligently for change, applauding institutional resistance to his agenda (in the courts, in the intelligence community, in the White House itself) can seem like the unproblematically patriotic thing to do. But what if the president were competent, knowledgeable, and even-keeled? Would he have been permitted to improve relations with Putin instead of pushed to arm Ukraine? Would he have been allowed to distance the U.S. from NATO instead of reaffirming our commitment to fight a war over countries in Russia's near-abroad? Would he have been supported in his efforts to admit fewer immigrants to the country?

Or are all of these issues, and many others, now considered locked in, inevitable, immobile — with the effort to adjust them presumed to be off-limits?

If this is the position of those who work within the institutions of the federal government (and especially the executive branch), that portends an ominous future. Denying the democratic will doesn't necessarily lead that will to dissipate. On the contrary, resistance can provoke it further, leading it to grow more powerful and more radicalized as it begins to view the very institutions of government as the obstacle to getting its way. The hope of avoiding this kind of situation led the early liberals in a much less democratic age to propose elections as a means of ensuring some measure of representation for public opinion in the halls of power. Today our representational expectations are far higher. Democratic institutions are presumed to be permeable and responsive to the popular will. When they aren't, voters begin to view them as illegitimate.

The problem didn't start with Donald Trump, but he makes it far worse — by giving democratically unresponsive institutions a high-minded justification for doubling down on the status quo at the very moment when popular agitation on both the right and the left is demanding more dramatic change. (Would a democratic-socialist president be permitted to pass and implement a single-payer health-care system? Or would the courts immediately declare it unconstitutional? We may find out with the election of our next Democratic president.)

This may be the paradoxical way that Trump contributes to the longer-term breakdown to democracy in the United States: Not by seizing power in the name of the people, but by inadvertently demonstrating that the people possess remarkably little power under the current system to change anything significant at all.

In a democratic age, that is unlikely to go down well.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

September 7 editorial cartoons

September 7 editorial cartoonsCartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include stressing about Powerball, and a busy FBI schedule

-

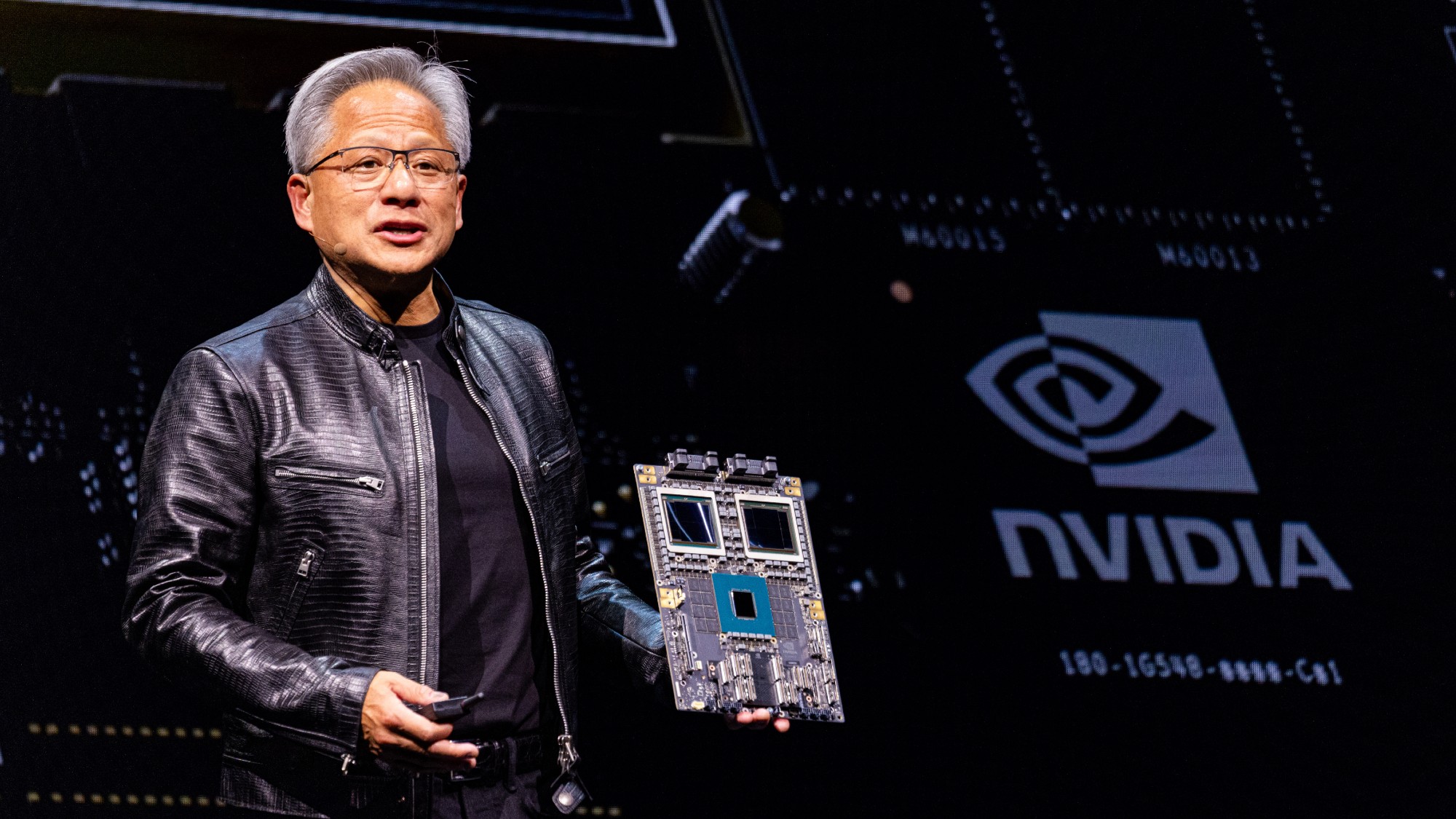

Nvidia: unstoppable force, or powering down?

Nvidia: unstoppable force, or powering down?Talking Point Sales of firm's AI-powering chips have surged above market expectations –but China is the elephant in the room

-

5 hard-working cartoons about Labor Day celebrations

5 hard-working cartoons about Labor Day celebrationsCartoons Artists take on creation of AI, spelling mistakes, and more

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event