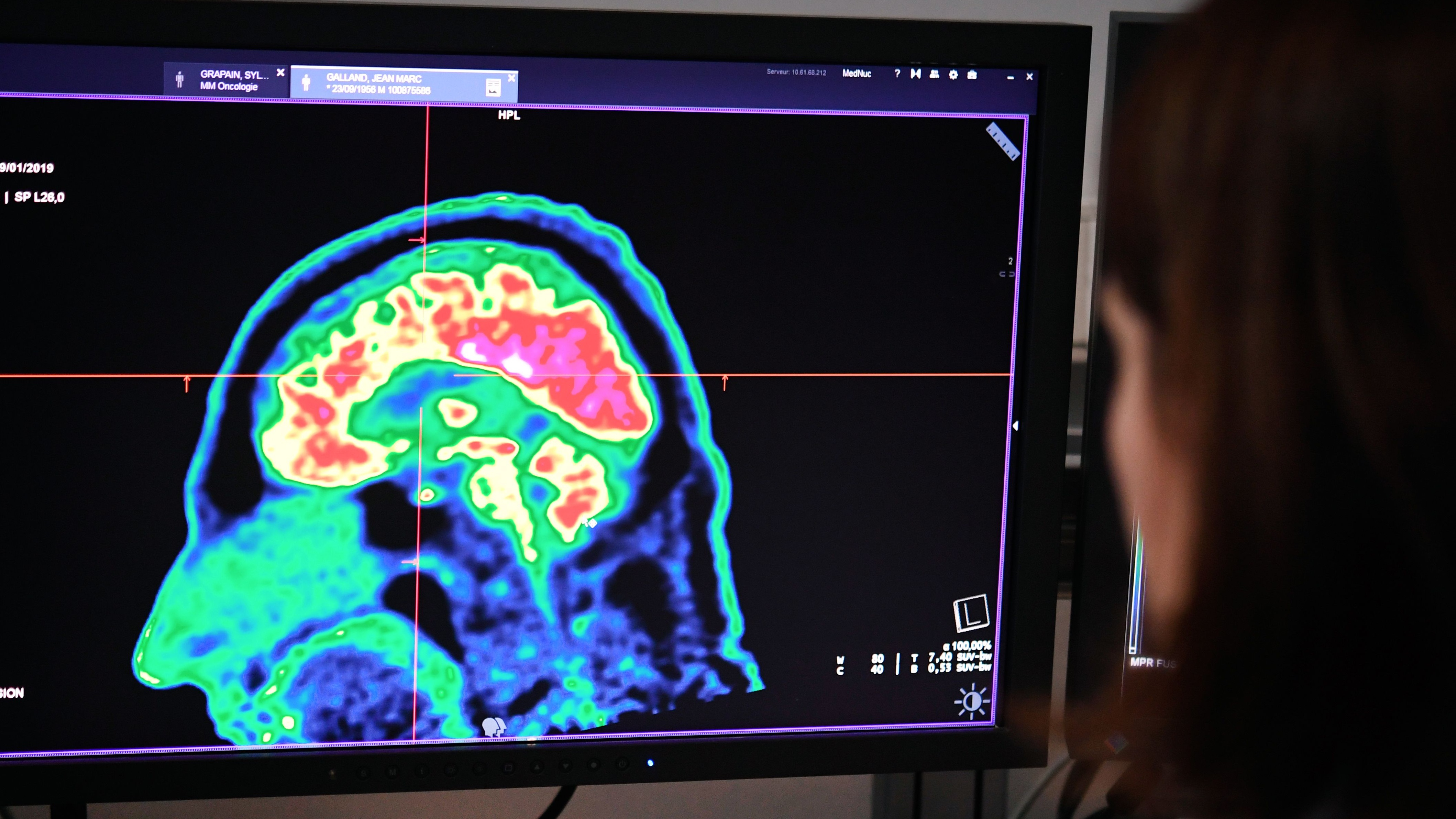

Lasting impact: how Covid damages the human brain

New research suggests coronavirus complications may include stroke and psychosis

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Doctors have repeatedly warned that coronavirus patients may be left with life-altering health problems - and now new research has shone a light on the threat posed to the body’s most vital organ.

Brain complications including stroke and psychosis have been linked to Covid-19 in a study “that raises concerns about the potentially extensive impact of the disease in some patients”, The Guardian reports.

Experts say the findings “highlight the need to investigate the possible effects of Covid-19 in the brain and studies to explore potential treatments”, the newspaper adds.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Covid and the brain

The study, published in The Lancet, looked in detail at 125 “severe cases” of Covid in the UK. The data was collected between 2 April and April 26, “when the disease was spreading exponentially” across the country, says The Telegraph.

The most common brain-related complication seen was stroke, which was recorded in 77 of the patients. Most of those affected were over 60 years old, and the strokes were ischaemic - caused by a blood clot in the brain.

In the remaining stroke cases, nine patients had a brain haemorrhage, and one had a stroke caused by inflammation in the blood vessels of the brain. Covid has previously been found to “cause severe inflammation and blood clots in the lungs and elsewhere in the body”, The Guardian reports.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As well as strokes, the study found that a number of the patients experienced “confusion or changes in behaviour reflecting an altered mental state”. Seven of these patients were also found to have suffered inflammation of the brain, known as encephalitis.

The patients with altered mental states were later diagnosed with a range of psychiatric conditions including psychosis, a dementia-like syndrome and mood disorders.

A first in the field?

While the newly published study is one of the largest yet on brain complications and Covid, scientists have been hinting at a possible link since the early days of the pandemic.

In March, medics at Strasbourg University Hospital in northeast France reported that in some severe Covid cases, patients appeared to be “extremely agitated” and were experiencing “neurological problems” including “confusion and delirium”.

Julie Helms, a doctor at the hospital, told the BBC that “we are used to having some patients in the ICU who are agitated and require sedation, but this was completely abnormal”.

“It has been very scary, especially because many of the people we treated were very young – many in their 30s and 40s, even an 18-year-old,” she added.

Helms’ team reported their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine, describing signs of “encephalopathy”, the general medical term for damage to the brain.

Signs of brain damage in coronavirus patients had also been noted back in February by researchers in Wuhan, the Chinese city at the centre of the global outbreak.

Earlier this month, the Financial Times reported that researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore had found “the first direct evidence that coronavirus could infect the human brain and replicate inside its cells”.

In tests, the scientists added low levels of Sars-Cov-2, the virus that causes the disease, to “tiny neuronal balls known as mini-brains that are grown from human stem cells”, says the newspaper. They observed how the “virus infected neurons in the mini-brains… [and] then multiplied within the neurons”.

Within three days, the study found the number of copies of the original Covid virus had increased “at least tenfold”.

According to the BBC, more than 300 studies across the globe have found “a prevalence of neurological abnormalities in Covid-19 patients”. The extent of the problem remains unclear, but experts estimate that “roughly 50% of patients diagnosed with Sars-CoV-2... have experienced neurological problems”, says the broadcaster.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

So what happens next?

Sarah Pett, who co-led the new study, says that while the findings are not conclusive, the research forms an “important snapshot of the brain-related complications of Covid-19 in hospitalised patients”.

“It is critically important that we continue to collect this information to really understand this virus fully,” added Pett, a lecturer in infectious disease at University College London.

That call has been echoed by other scientists.

Michael Sharpe, a professor of psychological medicine at the University of Oxford, said that the report “reminds us that Covid-19 is more than a respiratory infection and that we need to consider its link to a variety of other illnesses”.

However, “people in the general population should not worry too much about these possibly associated illnesses as they are probably relatively rare”, he added.

Emphasising that point, study co-leader Benedict Michael, a senior clinician scientist fellow at Liverpool University, “said it was important to note that the study focused on severe cases”, The Telegraph reports.

But Michael noted that the research was an important step towards defining Covid-19’s effect on the brain, adding that “we now need detailed studies to understand the possible biological mechanisms ... so we can explore potential treatments”.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youth

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youthIn The Spotlight Obsession with beating biological clock identified as damaging new addiction

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

How space travel changes your brain

How space travel changes your brainUnder the Radar Space shifts the position of the brain in the skull, causing orientation problems that could complicate plans to live on the Moon or Mars

-

How dangerous is the ‘K’ strain super-flu?

How dangerous is the ‘K’ strain super-flu?The Explainer Surge in cases of new variant H3N2 flu in UK and around the world

-

Choline: the ‘under-appreciated’ nutrient

Choline: the ‘under-appreciated’ nutrientThe Explainer Studies link choline levels to accelerated ageing, anxiety, memory function and more

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system