Coronavirus: how the UK’s response to expert advice compares with other EU countries

Germany and Sweden followed their scientists to the letter - with very different outcomes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the UK topping the EU table that no country wants to lead, Downing Street is facing growing pressure to curb the nation’s rising Covid-19 death toll.

After coming under fire for failing to act quickly during the early weeks of the coronavirus pandemic, No. 10 is facing further flak following the publication of documents that show the government has ignored advice from its senior scientific advisers.

Experts on the Scientific Advisory Group on Emergencies (Sage) urged ministers to introduce an immediate “circuit breaker” lockdown last month, the papers show. But Downing Street opted instead for localised restrictions despite warnings that more drastic action was needed to stem infections.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So what can we learn from countries with leaders who did follow the science?

Uber-efficiency

Since the virus arrived in Europe, Germany has been championed as a nation that responded quickly and efficiently to the threat.

The country has so far reported 337,314 cases and 9,685 related deaths in a population of 83 million, according to latest figures. By contrast, the UK, with a population of 67 million, has recorded 637,725 cases and 43,108 deaths - a higher tally of fatalities than any other country in the EU and the fifth-highest in the world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In April, Germany’s leading coronavirus expert Christian Drosten told The Guardian that “people are claiming we overreacted” and that there was “political and economic pressure to return to normal”.

“For many Germans, I’m the evil guy who is crippling the economy,” said Drosten, director of the Institute of Virology at the Charite Hospital in Berlin. The scientist revealed that he had received death threats after advising the country to enter a full lockdown early in the pandemic.

But importantly, Droseten does have the full support of Angela Merkel.

The chancellor - who has a doctorate in quantum chemistry and previously worked as a research scientist - has reinvented herself as “less a commander in chief and more a scientist in chief”, says The Atlantic.

From the outset, Merkel has “relied on experts from well-funded scientific-research organisations, including public-health agencies such as the Robert Koch Institute and the country’s network of public universities”, the magazine continues.

And Merkel’s faith in Germany’s scientific community has been echoed in the public’s trust in the her, Kekst CNC polling shows.

The chair of the Berlin Institute of Health, Axel Radlach Pries, told The Atlantic “that what [Germans] get from both Drosten and Angela Merkel are real and very well-considered facts”.

Because they are “honest with respect to their information”, Pries added, the public follow their rules, creating “a very calm situation in Germany”.

Swedo-science

While Germany serves as a lesson in trusting the experts, Sweden’s anti-lockdown coronavirus experiment has proved far more controversial.

On the advice of chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell, leaders in Stockholm have refused to impose lockdowns, insisting that doing so would be akin to “using a hammer to kill a fly”. But data on Covid infections and deaths in Sweden tells a different story.

Sweden has reported more than five times as many coronavirus deaths per capita as neighbouring Denmark, and around ten times as many as Finland or Norway.

And Tegnell’s previous claim in that up to 30% of Sweden’s population could be immune to Covid-19 is “backed up by little data”, says Business Insider.

Health experts had predicted that 40% of the population in Stockholm would have developed antibodies to the disease by May. But the actual figure was 17%, according to a review of evidence published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. The comparable figure for London was also 17%.

Sweden’s economy has fared badly too, with GDP falling by 8.6% in the second quarter of 2020 - a “record decline” that was “significantly worse than even the fourth quarter of 2008, when the Nordic country recorded a fall of 3.8% during the global financial crisis”, CNBC reports.

David Oxley, senior Europe economist at Capital Economics, told the broadcaster that Sweden’s sharp GDP contraction “confirms that it has not been immune to Covid, despite the government’s well-documented light-touch lockdown”.

‘Sick of experts’

Back in 2016, in the run-up to the referendum on whether Britain should quit the EU, Michael Gove claimed that “the people of this country have had enough of experts, with organisations with acronyms saying that they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong”.

But since the onset of the Covid pandemic, Johnson has “claimed his government was following the science at every step of its plan for dealing with the coronavirus”, says CNN.

Unlike both Germany and Sweden, however, the prime minister now appears to be sidelining the advisers whom he had previously placed front and centre.

At a press conference on Monday, England’s Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty (pictured top, left) said he was not confident that Johnson’s latest measures “would be enough to get on top of” outbreaks across the UK.

The scientist’s warning has fuelled fears that Gove’s scathing verdict on experts has become government policy at a pivotal moment for the country.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?Today’s Big Question Kyiv secures crucial funding but the EU ‘blinked’ at the chance to strike a bold blow against Russia

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

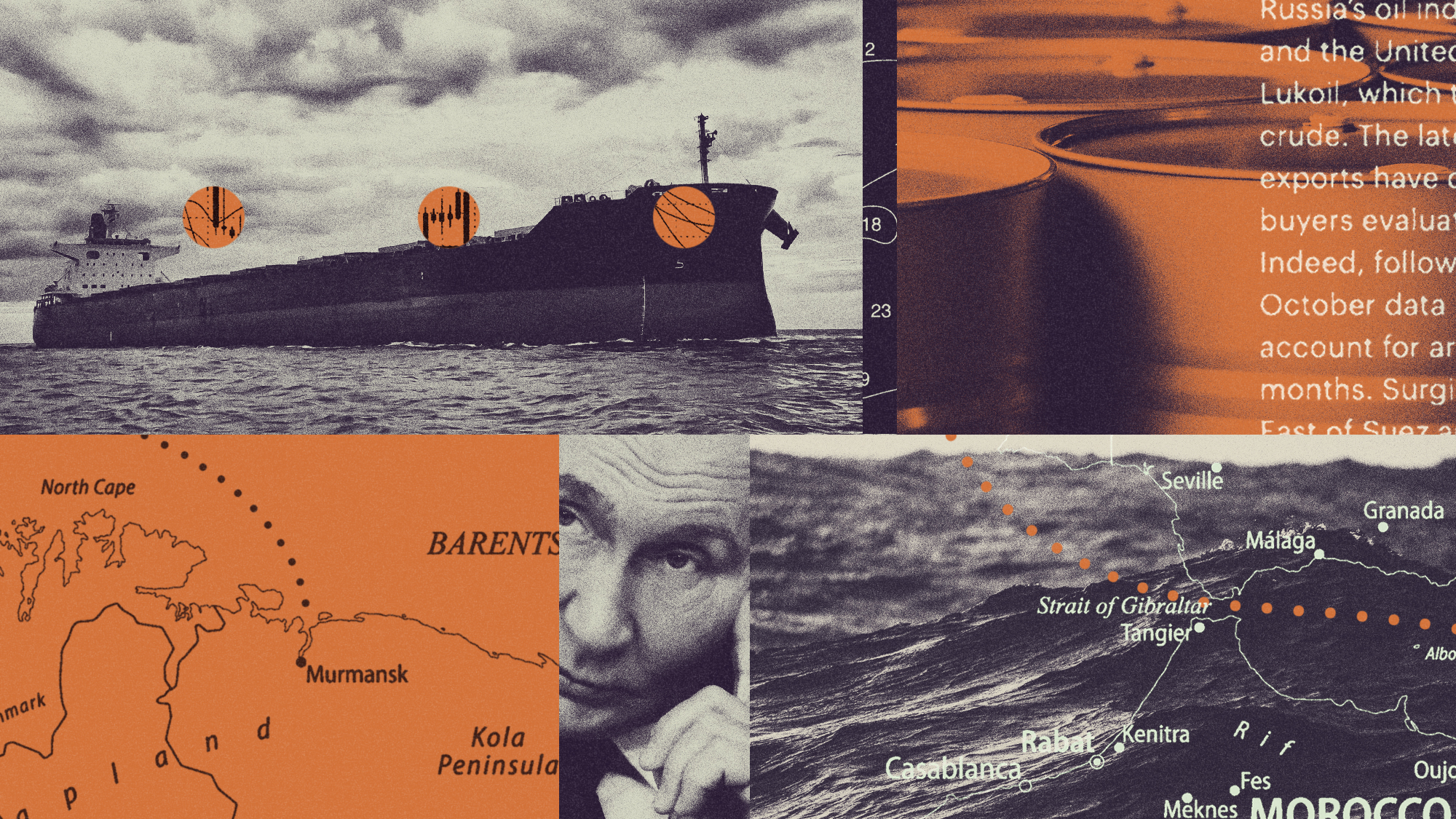

Defeating Russia’s shadow fleet

Defeating Russia’s shadow fleetThe Explainer A growing number of uninsured and falsely registered vessels are entering international waters, dodging EU sanctions on Moscow’s oil and gas

-

Asylum hotels: everything you need to know

Asylum hotels: everything you need to knowThe Explainer Using hotels to house asylum seekers has proved extremely unpopular. Why, and what can the government do about it?

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Behind the ‘Boriswave’: Farage plans to scrap indefinite leave to remain

Behind the ‘Boriswave’: Farage plans to scrap indefinite leave to remainThe Explainer The problem of the post-Brexit immigration surge – and Reform’s radical solution