What is halal meat and is it cruel to animals?

Islamic ritual slaughter has been attacked by animal welfare groups, but Muslim authorities say the method is humane

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The debate around halal meat is once again back in the spotlight after MPs expressed concern for the welfare of animals slaughtered without first being stunned in abattoirs producing halal meat.

The Westminster Hall debate in June drew a fiery exchange from those from across the political spectrum, with Lib Dem MP Rachel Gilmour describing the practice as “not only outdated but barbaric”. In response Yasmin Qureshi, a Labour MP, said a lot of opposition to halal was not about “animal welfare” but “prejudice, plain and simple”.

Halal slaughter is intended to be a humane, ethical and hygienic method of dispatching animals raised for consumption, yet the practice, which traditionally does not include the animal being pre-stunned before death, has consistently been criticised by animal-welfare groups as unnecessarily cruel.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is halal?

Halal is a word regularly used to refer to food, specifically the slaughter and preparation of meat, by non-Muslim people. But its meaning is more far-reaching.

“Halal” translates as “permissible” in Arabic, and refers to any action or behaviour that is allowed in Islam, including what types of meat and methods of preparation are acceptable. Conversely, “haram” refers to impermissible or unlawful actions.

Halal meat is a key element of Islamic dietary laws, covering not only the types of animal that can be consumed by practising Muslims but also the way in which those animals are killed.

How is halal meat prepared?

God’s name must be invoked in a one-line blessing called the Tasmiyah, said before any slaughter. British Halal Food Authority slaughtermen use the most common version, “Bismillahi-Allahu Akbar” (In the name of Allah the greatest).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Reciting a short blessing beginning with “bismillah” (in the name of Allah) is a prerequisite for Muslims before embarking on any significant task.

The Islamic method of killing an animal for meat is called zabiha. After reciting the blessing, the slaughterman uses a surgically sharp instrument to cut the animal’s throat, windpipe and the blood vessels around its neck. The blood is then allowed to drain from the body.

Only one animal can be ritually slaughtered at a time and the other animals must not witness any death.

Do the animals feel pain?

Outside religious use, non-stunned slaughter was widely abandoned in the 20th century and is increasingly perceived as cruel. But non-stunned slaughter continues to be permitted for religious purposes, and the question of whether it is more or less humane than other forms is a matter of debate.

Some studies suggest religious slaughter can be as “humane as good conventional slaughter methods” when performed “properly”, said the Islamic Services of America.

Animal-health experts and campaigners disagree. The RSPCA argues that killing animals without stunning them causes them to “experience suffering and distress”, and has urged the UK government to ensure all animals are unconscious when slaughtered.

The British Veterinary Association calls for all animals to be effectively stunned before slaughter because of the “pain, suffering and distress” experienced during the cut and bleeding

How is halal meat regulated?

Both European and UK law “requires animals to be stunned before being killed”, though there are exemptions for religious slaughter in approved abattoirs, said the BBC.

The British government has repeatedly resisted pressure from animal welfare groups such as the RSPCA to outlaw halal slaughter without pre-stunning. It has also opposed EU measures that require meat to carry labels confirming whether it came from animals that had been stunned before slaughter, despite a 2021 poll finding more than 70% of Brits support this.

This was reflected in June’s debate, in which “many MPs – including those who object to a ban on non-stun slaughter – did support mandatory labelling for non-stun meat”, said the National Secular Society.

Qureshi, who opposed the petition that prompted the debate, said she was “very happy” for halal meat to be labelled, while Independent MP Shockat Adam said it was his “firm conviction that many Muslim communities support clear, accurate labelling”.

How widespread is halal meat in the UK?

According to one of Britain’s foremost vets, many non-Muslim Britons are inadvertently eating meat from animals slaughtered while they are still conscious. Writing in the Daily Mail, Lord Trees, a former president of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, said that, with the sharp rise in the number of sheep and poultry being killed in accordance with halal practice, it was highly probable that some unstunned meat was entering the “standard” food chain, mainly in pies and ready meals.

Awal Fuseini, senior sector manager at the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, told Farmers Weekly that the halal meat market in the UK is one that farmers and processors can no longer ignore.

“Even though Muslims represent just 6.5% of the population, currently, 72% of the sheep slaughtered in England and Wales are killed according to halal processes”, as well as 56% of goats, 5% of calves and 4% of cattle.

According to a report, by the Halal Monitoring Committee and the University of Huddersfield featured on Islamic economy insights platform Salaam Gateway, the UK’s halal meat industry is valued at £1.7 billion and is expected to swell to almost £2 billion by 2028.

Globally, the halal meat industry is worth more than $4.5 billion, according to the Halal World Institute, and the “increasing Muslim populace globally is significantly contributing to the marketplace’s increase”.

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

Church of England instates first woman leader

Church of England instates first woman leaderSpeed Read Sarah Mullally became the 106th Archbishop of Canterbury

-

God is now just one text away because of AI

God is now just one text away because of AIUnder the radar People can talk to a higher power through AI chatbots

-

Religion: Thiel’s ‘Antichrist’ obsession

Religion: Thiel’s ‘Antichrist’ obsessionFeature Peter Thiel’s new lectures cast critics of tech and AI as “legionnaires of the Antichrist”

-

Pope Leo wants to change the Vatican’s murky finances

Pope Leo wants to change the Vatican’s murky financesThe Explainer Leo has been working to change some decisions made by his predecessor

-

Pope Leo canonizes first millennial saint

Pope Leo canonizes first millennial saintSpeed Read Two young Italians, Carlo Acutis and Pier Giorgio Frassati, were elevated to sainthood

-

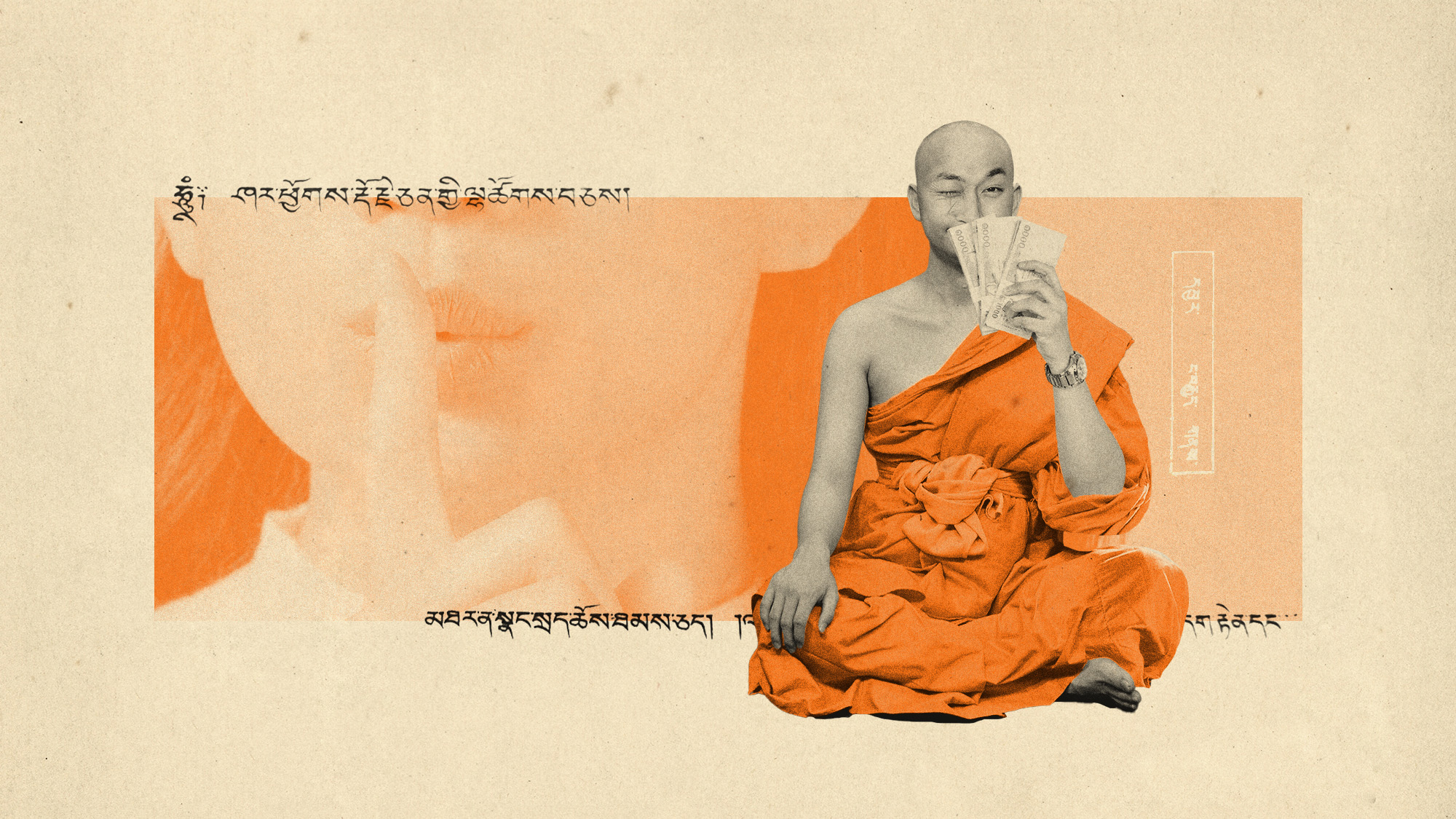

Thailand's monk sex scandal

Thailand's monk sex scandalIn The Spotlight New accusations involving illicit sex and blackmail have shaken the nation and opened a debate on the privileges monks enjoy

-

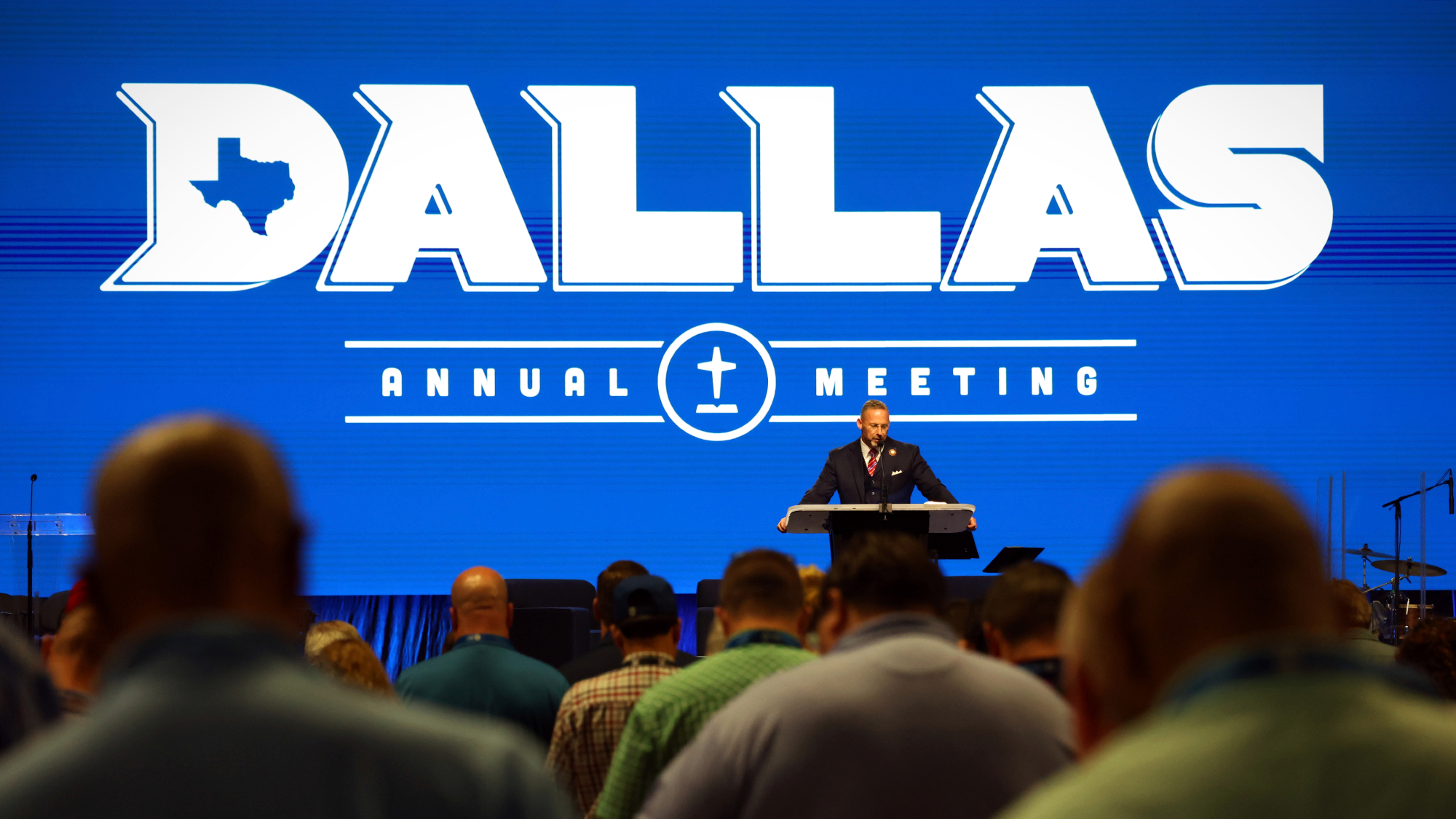

Southern Baptists lay out their political road map

Southern Baptists lay out their political road mapThe Explainer The Southern Baptist Convention held major votes on same-sex marriage, pornography and more

-

Southern Baptists endorse gay marriage ban

Southern Baptists endorse gay marriage banSpeed Read The largest US Protestant denomination voted to ban same-sex marriage and pornography at their national meeting