Where is the lost island of Atlantis and could it be real?

Plato's story of a utopian civilisation in the Atlantic Ocean still captures our imagination today

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

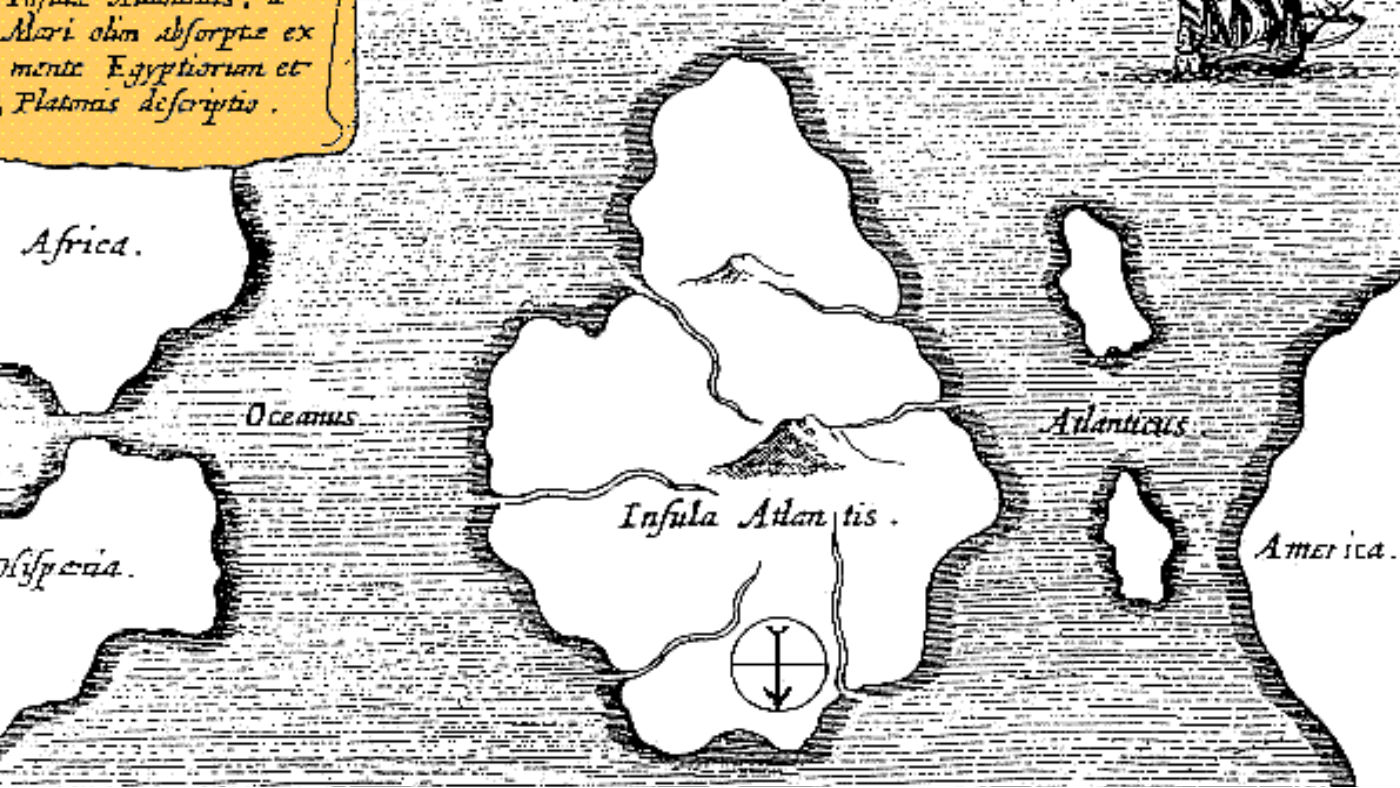

It was the philosopher Plato who first wrote about the island of Atlantis, which was said to have disappeared into the ocean after falling out of favour with the gods.

"It's clear that Plato made up Atlantis as a plot device for his stories because there are no other records of it anywhere else in the world," says Live Science. But this hasn't stopped public fascination with the idea of a sunken civilisation lost in the sea.

Where did the story of Atlantis come from?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Plato wrote about the lost island, with a great capital city, in his works Timaeus and Critias around the time of 360 BC, and described it as having existed 9,000 years before his time.

Its founders were said to be half god, half human. They lived as an advanced, utopian civilisation and a great naval power, but became greedy and immoral, so were punished by the gods with a terrible night of fire and earthquakes that caused Atlantis to sink.

Today, Atlantis is thought of as a peaceful utopia, says Live Science, but Ken Feder, a professor of archaeology, says it was more like a "technologically sophisticated but morally bankrupt evil empire" that was attempting "world domination by force". In Plato's Atlantean dialogues – likened by Feder to an early version of Star Wars – it acts as an opponent to the perfect society of ancient Athens.

Where would Atlantis be?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Plato was "crystal clear" about where Atlantis was, says Live Science. "For the ocean there was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, 'the pillars of Heracles,' (i.e., Hercules) there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together," he wrote.

In other words, it lies in the Atlantic Ocean beyond "the pillars of Hercules", the Strait of Gibraltar, at the mouth of the Mediterranean. "Yet it has never been found in the Atlantic, or anywhere else," says the website.

Nevertheless, Plato's tale has inspired differing theories over the years about where Atlantis could be. "Pick a spot on the map and someone has said that Atlantis was there," Charles Orser, curator of history at the New York State Museum in Albany, told National Geographic. "Every place you can imagine."

Could there be any truth in the story?

"Few, if any, scientists think Atlantis actually existed," says National Geographic, especially since there is no record of the island in earlier texts.

Ignatius Donnelly, a 19th-century writer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was said to be among the first people to take Plato's tale as fact. In his 1882 book, Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, he set out his theory that Atlantis existed and was the first region where man rose from a state of barbarism to civilisation and initiated most of the important accomplishments of the ancient world. The book inspired further works and theories.

Despite its "clear origin in fiction", thousands of books, magazines and websites are devoted to Atlantis, and it remains a popular topic in New Age circles, says Live Science.

"It's a story that captures the imagination," says James Romm, a professor of classics at Bard College in Annandale, New York. "It's a great myth. It has a lot of elements that people love to fantasise about."

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military