Britain's IPP prisoners shackled with indefinite terms

Imprisonment for Public Protection was scrapped in 2012, but more than 3,000 remain in custody

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The headlines tell a dire story about life behind bars for those serving indeterminate sentences.

"Prisoner 'trapped' 10 years into a 10-month jail sentence", BBC News reported on 30 May 2016.

This week, the BBC News headline read "Prisoner 'suicidal' 11 years into 10-month jail term".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The man in question, James Ward, is serving an Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentence, meaning he must prove that he's no longer a threat to the public in order to be released.

It was not violence towards others that led to his indeterminate sentence, but the fact he set fire to his cell mattress in 2006. Ward, who was 19 at the time, was serving a one-year sentence for assaulting his father and, according to his family, was "unable to cope" with prison life.

Ward, who has mental health problems, was given a minimum tariff of 10 months for his act. More than a decade later, he's still behind bars, unable to meet the threshold required for his release and caught in a cycle of self-harm and depression.

Ward is not alone. According to the chair of the Parole Board, Nick Hardwick, there are more than 3,300 people in England and Wales serving IPPs with no release date. The description of Ward's experience, Hardwick told the Guardian, is "happening to hundreds and hundreds".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justice for all

IPPs were introduced in 2003 under former home secretary David Blunkett.

They were designed to shield society from dangerous, violent and sexual offenders, whose crimes were not severe enough to warrant a life sentence, but who posed a "significant risk".

Interpreted by many as an attempt to bolster the Labour government's perceived toughness on crime, IPPs were part of a package of reforms designed to secure "justice for all" – a rebalance required due to the defendant-focused nature of the criminal justice system, said critics at the time.

Stain on the criminal justice system

The reality was considerably different, however.

The sentence was "applied far more widely [than envisaged]", says the BBC. Rather than targeting dangerous criminals – increasing the prison population by an estimated 900 people – the sentence was awarded, at its peak, to 6,000 offenders.

Many of these included "petty arsonists, pub brawlers and street muggers", reports the New Statesman, while an investigation carried out by Vice News found that one person was given an IPP for causing damage to an allotment.

A series of people are subject to IPPs who "[never] posed a danger to anyone – let alone society at large", John Samuels QC, a retired Parole Board judge, told Vice.

Remaining in custody indefinitely can be mentally tortuous. Research found that people serving IPPs suffer higher rates of self-harm and suicide than the general prison population, which is already facing a mental health crisis.

Inmates who are released face at least 10 years on licence and risk being recalled to prison for minor breaches of their parole. This can cast an inescapable shadow. As one IPP convict told the BBC, "if my front door knocks, I'm worried it's going to be someone to take me back to prison".

In 2008, with the pressure of prison overcrowding and financial considerations, IPPs were only applied to serious offences carrying a tariff of more than two years.

In 2012, however, following an unfavourable ruling against the UK in the European Court of Human Rights, the coalition government abolished IPPs.

Ken Clarke, then justice secretary, denounced the indefinite sentence as a "stain" on the criminal justice system – one for which IPP inventor Blunkett has since expressed regret.

Kafka-esque

Despite the move to abolish IPPs, the changes don't apply retrospectively. Inmates already serving IPP sentences, such as Ward, are effectively trapped behind bars, forced to prove they no longer pose a risk to society in order to walk free.

Given that "Parliament agreed get rid of [IPPs] precisely because [they] hadn't worked as anybody intended", "it is quite absurd that there are people who might be there for the rest of their lives", Clarke said last year.

Inmates are often denied access to courses needed to demonstrate their rehabilitation, compounding the injustice, despite a 2012 court ruling.

It's a "Kafka-esque situation", Andrew Neilson of the Howard League for Penal Reform told the New Statesman. "You've got people in the system who need to prove they're no longer dangerous, but they have no means to do that".

Justice delayed is justice denied

The Parole Board has released 900 IPP prisoners over the past year – 20 per cent more than in previous years, reports the BBC. But Hardwick insists that ministerial action is required to shift the backlog of cases. He recommends altering the test required for release from: "Is there proof that they're safe?" to the more realistic threshold of: "Is there proof that they're dangerous?"

Peter Clarke, chief inspector of prisons, also concluded that policy change was required, the secretary of state being the "only person who's got the authority to get a grip" on the problem.

The Ministry of Justice lays responsibility at the door of the Parole Board, however, emphasising the need to improve the efficiency of the parole process.

For those inmates saddled with an IPP sentence, the allocation of blame is secondary to finding a resolution. Until then, prisoners like James Ward will be stuck in limbo, his loved ones living in fear of next year's headline.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

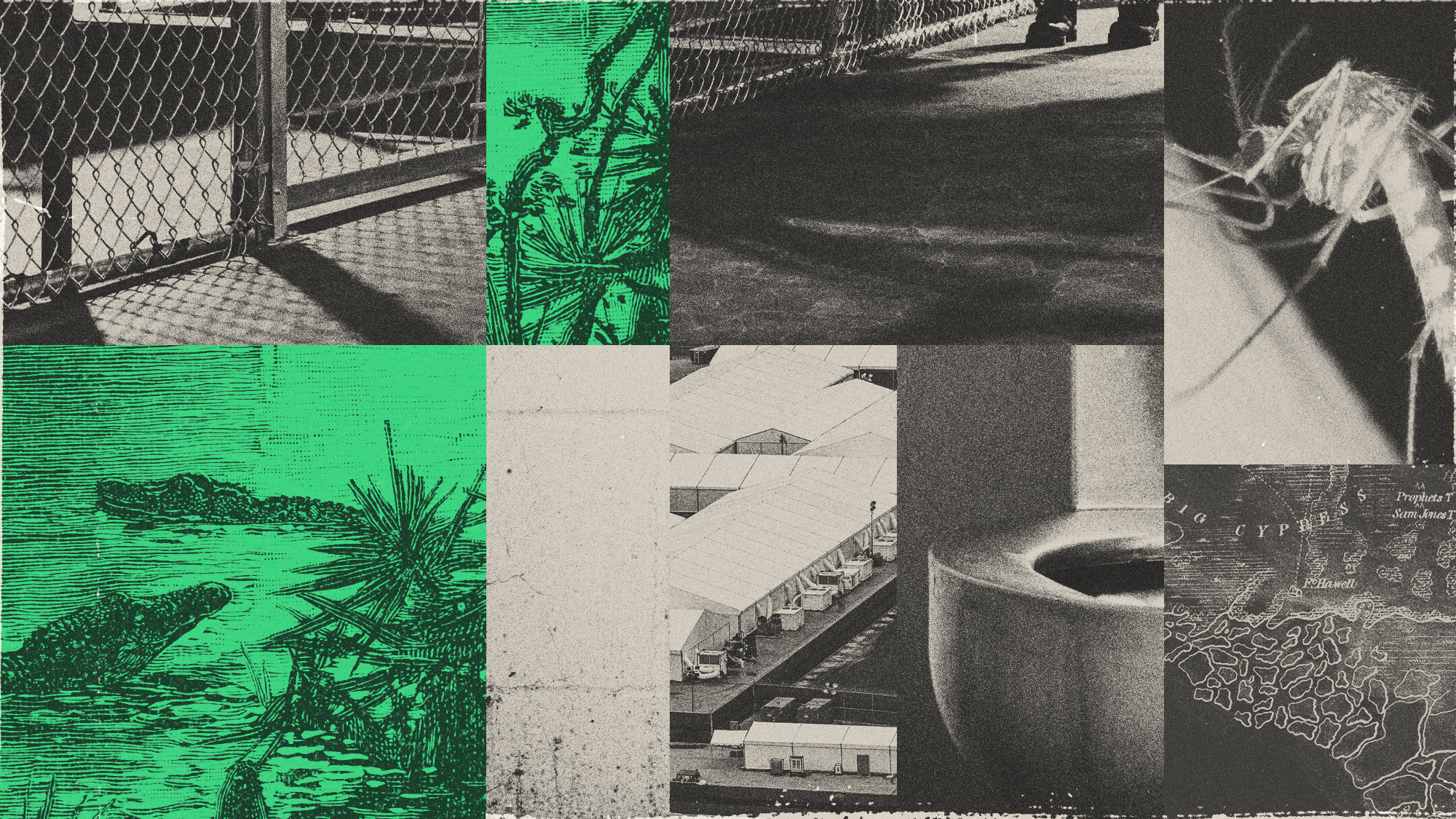

Insects and sewer water: the alleged conditions at 'Alligator Alcatraz'

Insects and sewer water: the alleged conditions at 'Alligator Alcatraz'The Explainer Hundreds of immigrants with no criminal charges in the United States are being held at the Florida facility

-

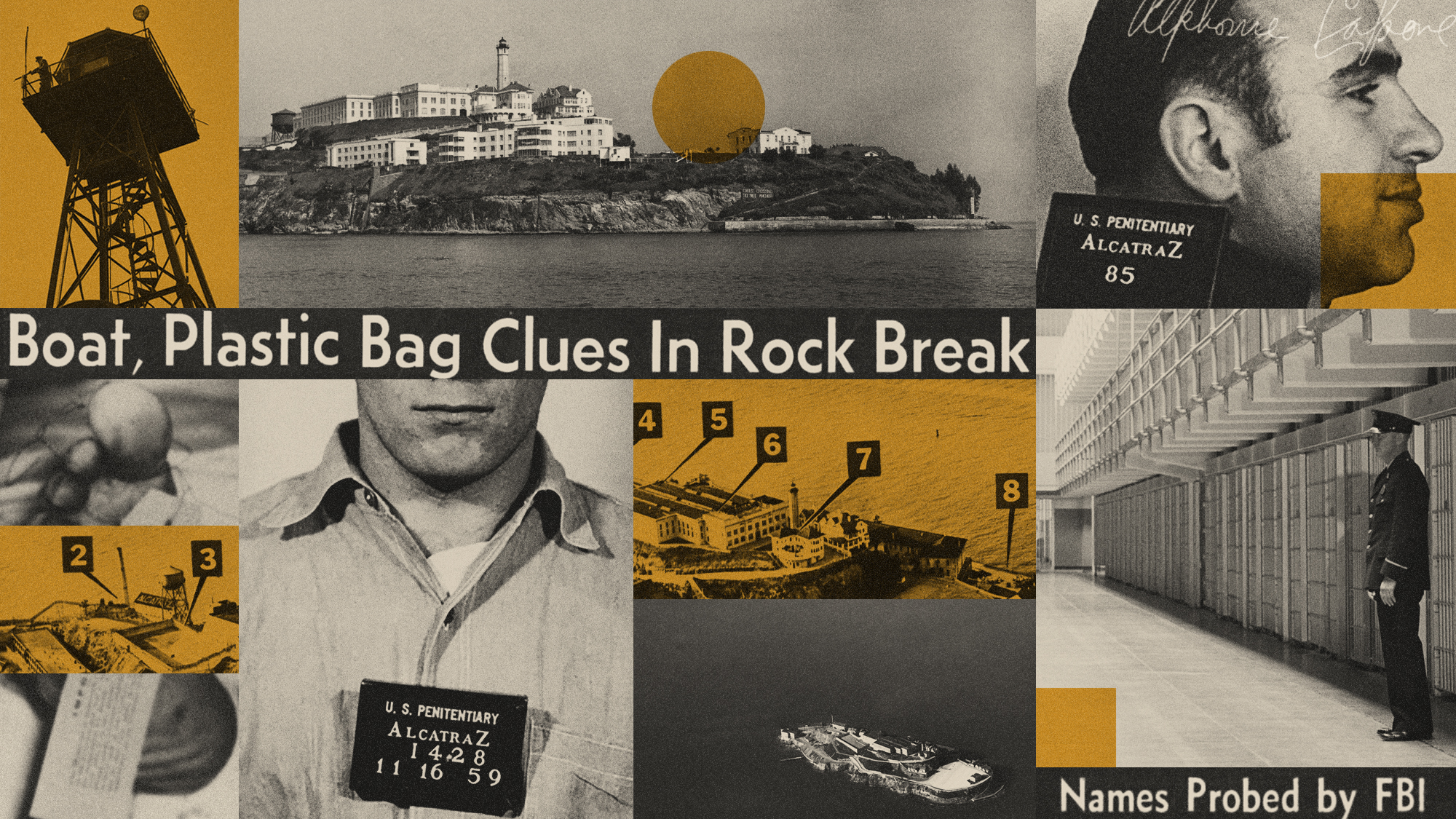

Alcatraz: America's most infamous prison

Alcatraz: America's most infamous prisonThe Explainer Donald Trump wants to re-open notorious 'escape-proof' jail for 'most ruthless and violent prisoners' in the US

-

Italy's prisons crisis

Italy's prisons crisisUnder the Radar Severe overcrowding, dire conditions and appalling violence have brought the Italian carceral system to boiling point

-

DOJ demands changes at 'abhorrent' Atlanta jail

DOJ demands changes at 'abhorrent' Atlanta jailSpeed Read Georgia's Fulton County Jail subjects inmates to 'unconstitutional' conditions, the 16-month investigation found

-

'Virtual prisons': how tech could let offenders serve time at home

'Virtual prisons': how tech could let offenders serve time at homeUnder The Radar New technology offers opportunities to address the jails crisis but does it 'miss the point'?

-

The countries that could solve the UK prisons crisis

The countries that could solve the UK prisons crisisThe Explainer Britain's jails are at breaking point, and ministers are looking overseas for solutions

-

DOJ investigates Tennessee's largest prison

DOJ investigates Tennessee's largest prisonSpeed Read Federal authorities are looking into reports of substantial violence and sexual abuse at Trousdale Turner Correctional Center

-

Tuscany's idyllic island prison with a waiting list

Tuscany's idyllic island prison with a waiting listUnder the Radar Europe's last island prison houses 90 inmates and makes wine that sells for $100 a bottle