Why half of UK adoptive families are struggling with violence

In Depth: One in four of Britain’s adoptive families are in crisis

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More than half of adoptive families have suffered child-on-parent violence, according to a survey of adoptive parents by the BBC and the charity Adoption UK.

Of nearly 3,000 parents who responded, three-quarters reported serious challenges with their placement, including developmental and behavioural problems, mental health issues and violence.

Overall, a quarter of adoptive homes are “in crisis”, the BBC said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Adoption UK, which provides support and advice to adoptive families, says calls to its helpline for families experiencing child-on-parent violence are on the rise. In 2015, the charity organised a sold-out conference that explained strategies for coping with aggressive children.

What are the challenges facing adoptive families?

On paper, the vast majority of adoptions are a success. The rate of disruption - when an adoption breaks down to the extent that the child leaves their adoptive family - is low.

A 2014 University of Bristol study tracked 37,335 adoptions in England over a 12-year period and estimated only 3.2% ended in a disruption.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, “in-depth analysis... showed that this low rate of disruption was down to the commitment and tenacity of parents who stuck by their children in extremely testing circumstances”, according to their report, Beyond the Adoption Order.

Violence towards the adoptive family was a factor in 86% of cases where a placement had ended in disruption, and was also present in the vast majority of cases where parents were struggling to cope with their adoptive child.

“We had not expected child-to-parent violence to feature so strongly in parental accounts of challenging behaviour,” said the study’s co-author, Professor Julie Selwyn. “Young people were mainly violent to their mothers, but fathers, siblings, pets and in one case, grandparents had also been assaulted.”

Who is most at risk?

The University of Bristol study found that adoptions of children aged four or older were 13 times more likely to end in disruption, suggesting that traumas linked to experiences prior to adoption are a major factor.

Out of 35 families where adoptions broke down, 91% of children had witnessed domestic violence and 34% had been sexually abused before they were adopted. All but one scored in the clinical range for at least one mental health problem, compared to 10% in the general population.

Past research has shown that adoptions of children who have had multiple placements in care are also more vulnerable to disruption, says Adoption UK. Instability is all too common, however - the 2014 report found instances where some young children were moved as many as 58 times.

What can be done to reduce the number of families in crisis?

Many adoptive parents experiencing challenging placements reported feeling isolated and ashamed at not being able to cope.

A mother who attended Adoption UK’s 2015 workshop on child-on-parent aggression told staff that she was “embarrassed” to admit that her 10-year-old son was attacking her, including once threatening her with a knife.

Families who do overcome the stigma of seeking out professional help with a severely troubled child often report that the services they have been offered were inadequate.

One woman, identified as “Jane”, told the BBC that when her adopted daughter began to exhibit extreme behavioural problems at age three, she found it impossible to access meaningful support through her local authority.

"The whole time we were saying: 'We're in trouble, she needs help; we need help.' But getting anything was a struggle,” she said. The family eventually ended the adoption and the child was returned to care.

The University of Bristol study found parents who reached out to social services “were rarely referred onto specialist services and were consequently offered the same ineffective interventions time and time again”. Some agencies had turned away families on the grounds that adopted children were not eligible for their support.

Accessing appropriate mental health care was a particular challenge, with nearly half of the 70 surveyed parents who had either gone through a disruption or were currently dealing with a challenging adoption saying they had paid for their child to undergo private therapy.

One of the report’s key recommendations is that local NHS child mental health services be required to either provide the necessary treatment or refer the patient to the appropriate facility in a timely manner.

Another of the report’s recommendations seeks to avert dysfunctional adoptions before they begin, in response to respondents’ comments that they had not been made aware of the full extent of their potential adoptee’s medical, developmental or emotional issues.

More than two-third of the parents who experienced troubled or terminated adoptions said they did not believe that had been given all of the relevant information about their adoptive child.

Social workers must ensure they provide “comprehensive and explicit information to adoptive parents with truthful information about the child”, the report says.

Has anything changed?

Since the publication of the Beyond the Adoption Order report in April 2014, a funding increase has altered the landscape of post-adoption services, offering new respite to families struggling to cope.

In May 2015, the Department for Education allocated £19m to an Adoption Support Fund (ASF). Subject to an assessment by their local authority, families in need can draw down up to £5,000 to pay for therapeutic services, including psychotherapy, art therapies, parenting workshops and family counselling.

In October 2016, the Department for Education announced that uptake for the ASF had been twice the expected number. As of 2017, almost 15,000 families are using the ASF.

Adoptive families who have used the fund reported “high levels of satisfaction”, according to an evaluation published by the Tavistock Institute for the Department for Education, with 84% saying the services provided had made a positive impact on their child.

One couple who were struggling to cope with a severely troubled teenage son with violent tendencies were blunt about the life-changing impact of the services, telling Adoption UK: “Without the therapeutic support we would have placed him back in foster care.”

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youth

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youthIn The Spotlight Obsession with beating biological clock identified as damaging new addiction

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

The app tackling porn addiction

The app tackling porn addictionUnder the Radar Blending behavioural science with cutting-edge technology, Quittr is part of a growing abstinence movement among men focused on self-improvement

-

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypes

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypesUnder the radar They could lead to more accurate diagnosis and care

-

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatine

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatineThe Explainer Popular fitness supplement shows promise in easing symptoms of everything from depression to menopause and could even help prevent Alzheimer's

-

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxiety

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxietyThe Week Recommends You can soothe your nervousness about flying before boarding the plane

-

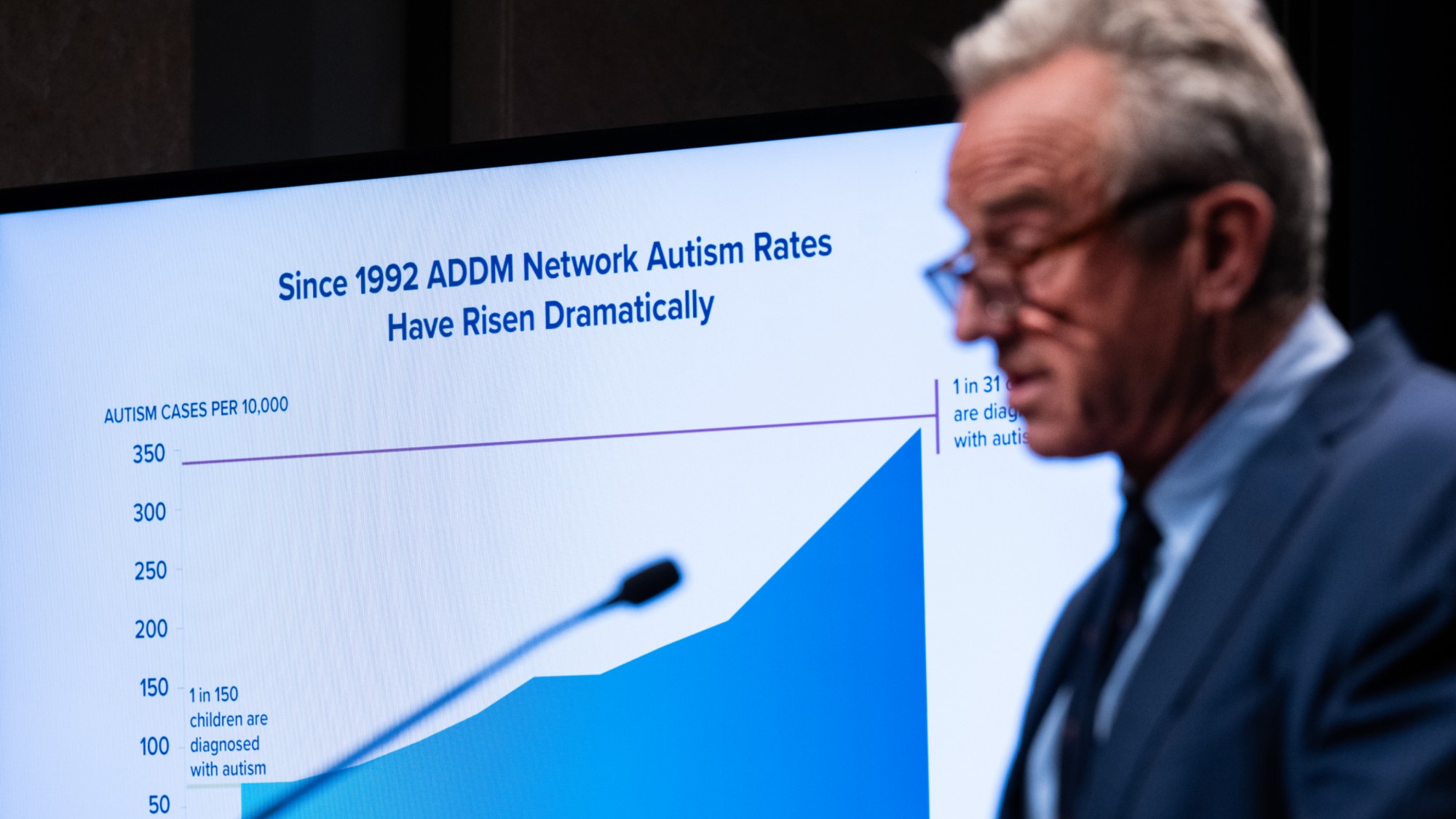

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchers

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchersIn the Spotlight Many of Kennedy's assertions have been condemned by experts and advocates

-

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?Talking Point Issues at 'the milder end of the spectrum' may be getting wrongly pathologised