Hawaii travel guide: living the island life

The islands of Oahu and Kauai are bite-sized delights, rich in history and culture - and spectacular landscapes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As British travellers seek ever more exotic destinations, you might have thought we’d flock to a cinematically handsome archipelago of English-speaking islands with a tropical climate, a rich cultural history, warm seas and boundless opportunity for adventure.

Yet each year fewer than 0.1% of us visit Hawaii. Thirty times more go to Belgium, which neither invented surfing nor contains an active volcano. There are notoriously few famous Belgians, but Hawaii has Barack Obama - and thanks to its American connections, it can even lay on a decent waffle.

Beach culture

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Precisely who first came up with the idea of riding the waves on a plank of wood is now lost to the sands of time, but Hawaiians have long claimed surfing as their national sport. They certainly got there before the Californians, according to the aptly named surf historians Stoner and Dunn, who recount the tale of three Hawaiian princes who wowed bathers at Santa Cruz with their “surf-board swimming” in 1885.

For novice Brits, the best place to dip a toe in the water is Waikiki, the beachfront district of high-rise Honolulu, where the waves are as friendly as the instructors. After a short briefing that covers the basics - lie at the back of the board, move to a crouch when the wave takes hold and then stand up, if you can - I paddle myself out to the surf zone.

My first attempt is a triumph, relatively speaking: I stand, or at least squat, for a good few seconds before I pitch into the Pacific. Take two is a bit of a disaster, but so much so that I’m still within reach of the instructor when I tumble off the board. He retrieves me and it, puts us back together again and launches me into another wave. After a wobble I steady myself and stay upright long enough to congratulate myself several times.

As the wave subsides I flop inelegantly into the water and a huge green turtle swims under me, swivelling its head in my direction, vaguely curious about all the fuss.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Hawaii is surrounded by waves of all shapes and sizes, among them the celebrated - and feared - Banzai Pipeline, which barrels onto the North Shore of Oahu island, about an hour’s drive from Honolulu. “The ultimate surfing wave,” says Surfer Today, it rears up over a shallow reef and rolls into the shore, propelling expert surfers through a tunnel of “beautiful chaos”. Alluring but deadly, it’s off limits to all but the most advanced. “When in doubt, stay out of the Pipeline.”

A world in microcosm

Step away from the Hawaiian coast and you could be almost anywhere on earth - or somewhere else entirely. Even the short drive across Oahu crosses terrain that might have been more at home in Scotland or Italy or south-east Asia. Pockets of heath and pine forest give way to grassland, mountains and rocky beaches, then dense rainforest that plunges directly into the ocean.

Hawaii’s geographic diversity - along with a few financial incentives - has not escaped the attention of Hollywood studios, which decamp to the islands whenever they need a stand-in for prehistoric Earth (Jurassic Park and its sequels and spin-offs), the South American jungle (Raiders of the Lost Ark), an enchanted Shakespearean isle (The Tempest) or 1970s Vietnam (Uncommon Valor, Tropic Thunder and many, many others).

At Kualoa Ranch, a 4,000-acre reserve north of Honolulu, I joined a minibus tour of movie locations and sets, venturing into the Indominus rex pen from Jurassic World, tossing around giant ape bones from Kong: Skull Island and hunkering down under the fallen log that sheltered Sam Neill from a flock of CGI dinosaurs in the original Jurassic Park.

Quite aside from the cinematic connections, this is an A-list location. In fact, a Godzilla footprint is arguably the least impressive feature of a landscape rich with dark peaks and lush valleys, hollowed out in the two million years since the island erupted from the seabed.

Oahu’s volcanic origin story is persuasively revealed by a visit to Diamond Head lookout, a brisk half-hour hike up a footpath that rises steeply from the Honolulu suburbs. It was only at the summit that I appreciated what I’d been climbing: the rim of a vast crater, more than 1,000 metres across.

It was hard to know which way to look. On my right was the crater itself, softened by half a millions years of weathering and a carpet of grass and trees, on my left the city and Waikiki beach, and behind me, from one horizon to the other, the Pacific. Now a purely recreational lookout point, a scattering of bunkers and pillboxes serve as a reminder that Diamond Head once had to earn its keep.

On the front line

Spin the globe until it’s centred on the Hawaiian islands and you’ll see almost nothing but blue. Yet these specks of rock, 2,500 miles from the US mainland and 4,000 miles from Japan, once played a pivotal role in world history.

On the morning of 7 December 1941, more than 350 Japanese aircraft approached Oahu, converging on Pearl Harbor, where eight US battleships were stationed. Soon all had been damaged and four of them sunk, inflicting serious damage on America’s capacity to wage war in the Pacific.

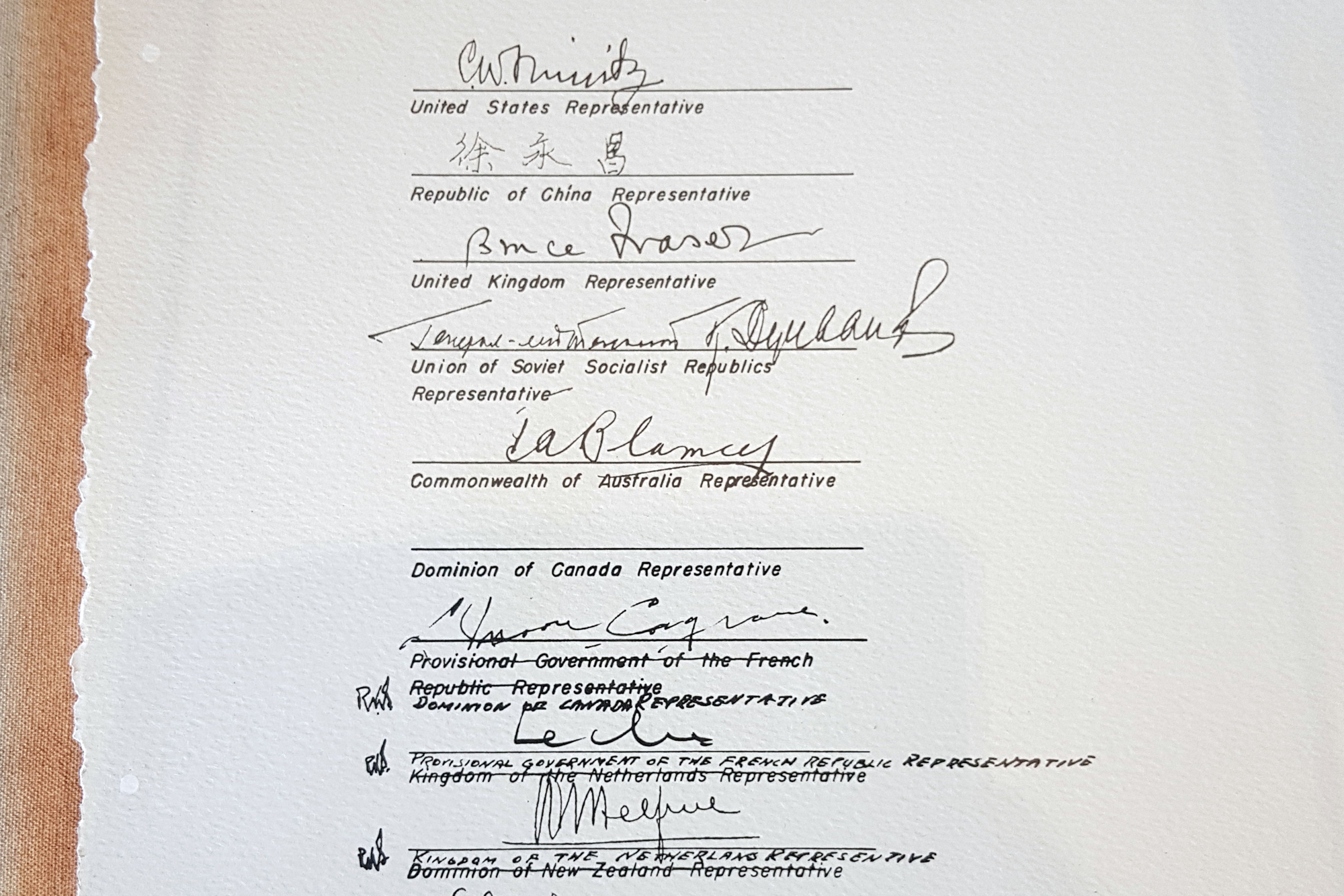

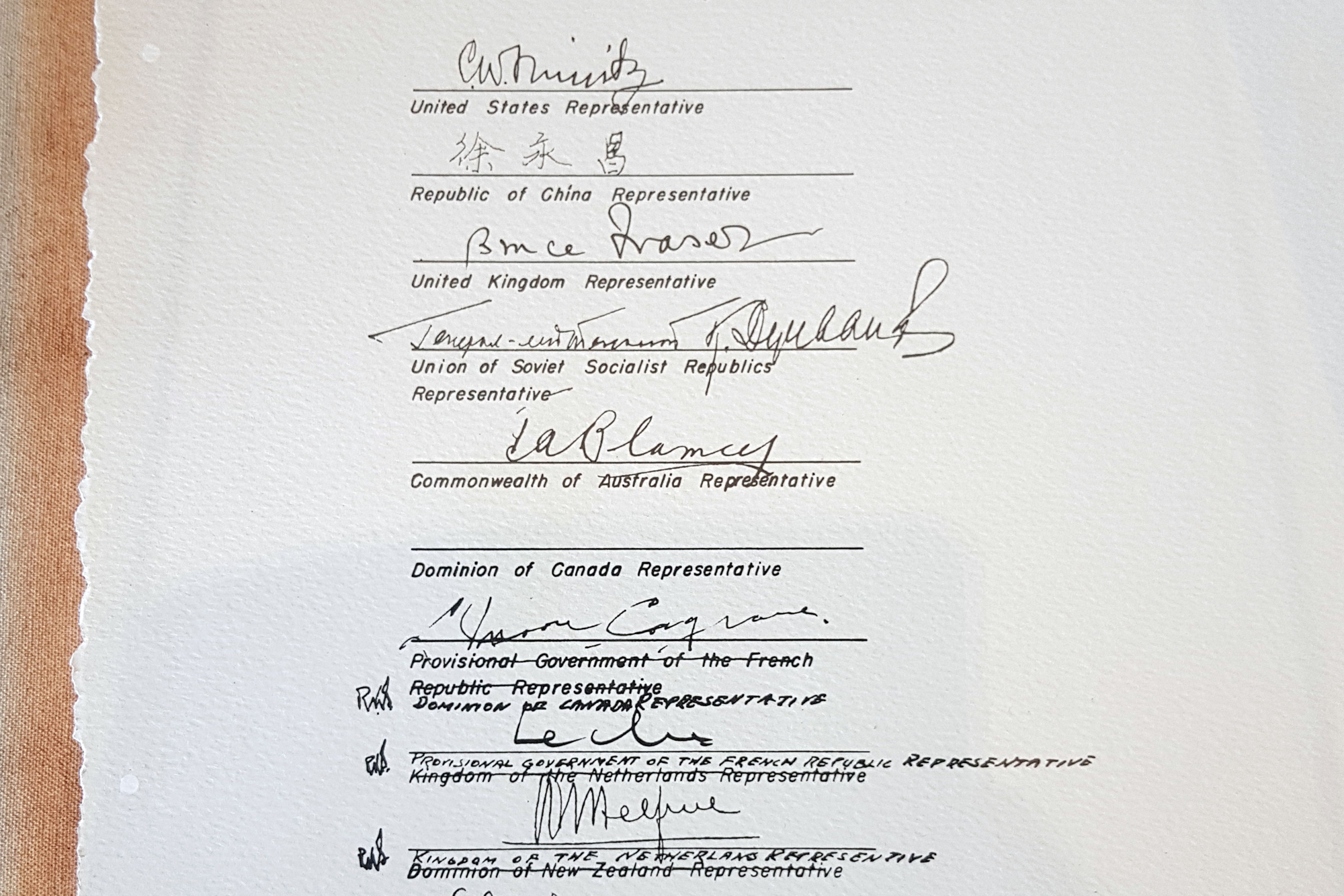

Pearl Harbor remains an active military base, but it’s also a museum and a memorial to the 2,335 Americans killed in the attack. Each year, more than a million people come to see the USS Arizona, the only stricken vessel to be left on the seabed rather than cut up and sold for scrap, and to climb aboard the USS Missouri, a formidable 270-metre battleship commissioned in the aftermath of the attack.

After a short tour, visitors are given a surprisingly free rein to explore the ship, above deck and below, and I soon got lost in the cavernous hull, a low panic rising as I hurried along empty corridors, past kitchens and mess halls and blocks of triple-decker bunk beds rammed into any spare space. The lack of daylight was disorientating and oppressive.

I would not have fared well during the Missouri’s active service, which bridged the gap between the Second World War - she hosted the formal ceremony of Japanese surrender - and the conflicts of our own generation. She was decommissioned only in 1992, having served in the first Gulf War. Footage of Tomahawk cruise missiles blasting off towards Baghdad, which I remember watching as a child, was filmed on her deck.

Conflict and unity

The attack on Pearl Harbor changed the course of Hawaiian history too, first dividing the many residents with Japanese heritage from the rest of the population and then binding the islands to the US mainland as the 50th state of the union.

Statehood was the latest turn in a twisty political history, which may have got under way as late as the ninth century AD. Historians disagree about precisely when Polynesian settlers came to the hitherto uninhabited islands, but most say they must have arrived from Tahiti between 100 and 800 AD. They formed several colonies which flourished and fought until the end of the 18th century, when Captain James Cook happened upon them and passed on European weaponry to their most powerful ruler, Kamehameha I.

Through exhibits and theatrical performances, the Polynesian Cultural Centre - an unusual mix of theme park and museum in northern Oahu - tells how he conquered the rest of the islands, establishing the united Kingdom of Hawaii. It lasted less than a century: in 1893, Kamehameha’s descendant, Queen Liliuokalani, was deposed by a group of American sugar plantation owners who wanted the islands to become an American territory so they would no longer be subject to US sugar tariffs. Formal annexation followed in 1898.

The centre also traces the islands’ links with other Polynesian societies scattered across the Pacific, from the Maoris of New Zealand, 5,000 miles south-west, to Pitcairn, 3,500 miles to the south-east. Their culture, along with a long history of immigration from Asia and the US mainland, has made modern Hawaii the most diverse state in the union.

By land, air and sea

Variety is a defining characteristic of Hawaii’s climate and geography as well as its people. The biggest island, called (confusingly) Hawaii or (less confusingly) The Big Island, contains eight of the world’s 13 climate zones, ranging from monsoon to desert to polar tundra. Even Kauai, a more temperate island at the north of the archipelago, has an astonishingly diverse range of weather conditions.

Mount Waialeale, for instance, receives an average of 11.4 metres of precipitation a year, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, and in 1982 was deluged with 17 metres of rain. Just a few miles away, a band of dry savannah has to make do with just 250mm.

The sun was shining when my short flight from Honolulu touched down at Kauai’s main airport, and I took advantage of the clear conditions to get straight back into the air for a scenic flight. Before take-off, the crew handed over a pair of surgical slippers to protect the delicate ecosystems of the interior of the island from any spores on my shoes - and a lifejacket to protect me from it.

A helicopter is the only way to get into the heart of Kauai, and Island Helicopters is the only company allowed to set down at Manawaiopuna Falls, which must be its most recognised landmark, even if few people could put it on a map. The 120-metre waterfall provides the backdrop to the arrival of Richard Attenborough and co in the opening moments of Jurassic Park.

It’s easy to see what caught Steven Spielberg’s eye: Kauai has an otherworldly beauty, its sharp-ridged mountains clad in an emerald patchwork of forest and grass. The Na Pali (“high cliff”) coast is particularly baroque. All that rain cascading down from Mt Waialeale has carved deep valleys into the mountainside and sculpted ripples into the cliffs, which rise 1,200 metres above the Pacific.

I felt humbled - and slightly nauseated - as the helicopter ducked and dived in the turbulent air, dipping down into a canyon and turning a slow pirouette to show off the landscape, the peaks looming above us. It may not feel like it, but there’s no safer way to see this isolated landscape: building roads is impossible, and an 11-mile walking trail is often on lists of the world’s most dangerous, due to the risk of flash floods and falling rocks.

Elsewhere on the island are more congenial footpaths, as well as countless other ways to explore the terrain. I spent a morning swooping over the forest canopy on a zipwire, an afternoon charging along river beds and red-earthed ravines at the wheel of an all-terrain vehicle, and all day sailing around it in a catamaran, snorkelling over a reef and keeping my eyes peeled for fins.

It wasn’t sharks we were looking for, but their friendlier seamates. We had spotted a pod of Pacific bottlenose dolphins just outside the harbour, and later in the day we would see pilot whales cresting the waves and spinner dolphins gliding alongside the catamaran.

On the return journey, as the crew handed out Hawaiian beers and the sun began to dip towards the horizon, I stood on the deck and looked towards the shore, scouring the empty, perfect beaches for signs of life. I tried to imagine what they would have looked like to Captain Cook, or the first Polynesian explorers, or the first American settlers as they prepared to land.

Kauai is small, no more than 30 miles across, and Hawaii as a whole is not a big place - no bigger than Belgium, as it happens. In its more sheltered places, it has barely changed since humans first set foot on them. But it has also been in constant flux, cultivated and trampled by one civilisation after another, shaped by the weather and the sea. Like few other destinations, you can grasp the whole of it in one trip - yet it contains a continent’s worth of history, geography and human life.

Planning your visit to Hawaii

Where to stay

On Oahu, the Hilton Hawaiian Village Waikiki Beach Resort has the prime spot in Honolulu, overlooking the beach and the surf zone. One of the first big hotels in Hawaii, it has since accommodated everyone from Elvis Presley to Margaret Thatcher, via Beyonce and the cast of Lost. From $1,799 (£1,300) for a seven-night stay.

On Kauai, the Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort and Spa has a glorious oceanfront setting, a saltwater lagoon for swimming, as well as several freshwater pools, a gym and and spa offering massages and other treatments. Tidepools restaurant also provides an excellent introduction to Hawaiian cooking, as well as a selection of international standards. From $3,150 (£2,275) for seven nights.

What to eat

Hawaiian cuisine has been informed by the islands many immigrants, and though the American influence is strong, traditional Polynesian foods are fighting a rearguard action.

Poke (extremely fresh fish, often yellowfin tuna, served raw with rice and sometimes mango) is light and deliciously summery, while poi, a purplish paste made from the ground-up root of the taro plant, will banish any residual carb cravings. Equally filling is moko loko, a dish consisting of crumbled hamburger meat served over rice, topped with a fried egg and doused in gravy. Try all of them at Liliha Bakery a Honolulu diner that’s been satisfying Hawaiian appetites since 1950 - and round off the experience with one (or more) of the 5,000 cream puffs they bake every day.

Another Hawaiian tradition is the “shrimp trucks” that sit at the roadside, serving up punnets of fried prawns doused in garlic, lemon and/or chilli butter. Giovannis, on the Kamehameha Highway at Haleiwa, is worth the drive in itself.

For authenticity of the more refined variety, head to 12th Avenue Grill in Honolulu, which sources as many ingredients as possible from Hawaiian farms and waters. Fresh fish is a speciality, as is the Hawaiian-reared steak and home-cured charcuterie. The zestily dressed market salad, enriched with beets, pistachios and other local goodies, offers a true taste of the island.

On Kauai, Gaylord’s restaurant offers an equally refined menu of seafood, steak and fresh Hawaiian produce, with the added attraction of outdoor tables and views of Mt Waialeale - or head for the Lanai Restaurant and Bar in Koloa, near the Grand Hyatt, where you can work up an appetite browsing the art shops and fashion boutiques along the street.

Finally, it would be remiss not to mention Hawaii’s unexpected passion for Spam. Waikiki stages an annual food festival dedicated to the product, in which chefs compete to prepare it in various inventive ways. In cafes and convenience stores around the island you will see it most often in the form of a Spam musubi, in which a slice of the canned meat has been grilled, laid on sushi rice and wrapped in nori. It may lack the delicacy of sushi, but it fills a hole.

When to go

Hawaii is a year-round destination, with daytime highs mostly somewhere between 25C and 30C. As a general rule, June is hotter and drier than December, but the difference between islands or between microclimates within islands can be greater than seasonal variations.

How to get there

United Airlines offers daily flights to Honolulu from London Heathrow and Edinburgh via various US cities. Economy return fares start at £946 from Heathrow and £930 from Edinburgh.

Netflights.com is offering seven nights in Hawaii, staying four nights at the Hilton Hawaiian Village Waikiki Beach Resort and three nights at the Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort and Spa and flights from Heathrow on United Airlines. Price starts at £2,479pp, based on selected dates in June 2018. Book by 1st April 2018.

For more information about visiting Hawaii, see www.GoHawaii.com/UK

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Hawai‘i: a kingdom crossing oceans – a ‘thrilling’ exhibition

Hawai‘i: a kingdom crossing oceans – a ‘thrilling’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends With some items on display for the first time since 1900, the British Museum’s new show gives voice to a ‘fascinating, rarely heard culture’

-

Experience the cool of these 11 stunning pools and lazy rivers this summer

Experience the cool of these 11 stunning pools and lazy rivers this summerThe Week Recommends You'll want to dive right in

-

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim Robinson

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim RobinsonThe Week Recommends 'Lampooning and embracing' middle-aged male loneliness, this film is 'enjoyable and funny'

-

At these 6 gnarly spots, both surfers and onlookers can catch a wave

At these 6 gnarly spots, both surfers and onlookers can catch a waveThe Week Recommends Be a (sort of) part of the action

-

This winter heed the call of these 7 spots for prime whale watching

This winter heed the call of these 7 spots for prime whale watchingThe Week Recommends Make a splash in Maui, Mexico and Sri Lanka

-

Take advantage of sublime October weather at these 7 hotels

Take advantage of sublime October weather at these 7 hotelsThe Week Recommends Rain, snow and sleet will absolutely not be keeping you from your destination

-

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptation

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptationThe Week Recommends Dumas's classic 19th-century novel is once again given new life in this 'fast-moving' film

-

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'The Week Recommends The final part of this trilogy deftly explores rising political tensions across the country