The curious linguistic history of pineapples and butterflies

One word is a historical outlier; the other a descendant of mythology

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pineapples and butterflies: two nice things, two odd words. Pineapples are neither pines nor apples. Butterflies are neither flies nor butter. But never mind that. Look at this:

Pineapple:

French: ananas

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Italian: ananas

Spanish: piña/ananá

Portuguese (European): ananás

German: Ananas

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Dutch: ananas

Swedish: ananas

Danish: ananas

Russian: ananas

Polish: ananas

Finnish: ananas

Estonian: ananass

Hungarian: ananász

Greek: ananás

Butterfly:

French: papillon

Italian: farfalla

Spanish: mariposa

Portuguese: borboleta

German: Schmetterling

Dutch: vlinder

Swedish: fjäril

Danish: sommerfugl

Russian: babochka

Polish: motyl

Finnish: perhonen

Estonian: liblikas

Hungarian: lepke, pillangó

Greek: petaloúda

Okay. So we have two big questions.

First, why does almost every European language but English call a pineapple "ananas"?

Second, why do they all have completely different words for butterfly?

The short answer: History and fantasy.

People in Europe had never heard of pineapples before the early 1600s. When the European invaders of the Americas brought the fruit back to Europe, they brought a word for it, too, same as they did with things like tomatoes and avocados. And the word, taken slightly changed from the Tupi language, was ananas.

So why didn't English go with that like just about everyone else did? We decided instead to use a word we already had that previously referred to pine cones. It's pine because it's spiky and apple because it's fruit. (Hey, French calls potatoes "earth apples" — pommes de terre.) We did use "ananas" a little bit back in the 1600s to 1800s, but pineapple prevailed. The fact that the word banana came over from West Africa (from the Wolof language) in the later 1600s probably helped pineapple win for clarity. Other languages didn't have another word to use, so they just stuck with ananas.

Butterflies, on the other hand, have been all over the world since before there were even people. They weren't imported all at one time. But that still doesn't account for why practically all of the different languages' words are different from one another. Words within language families tend to resemble each other. Butter, in the languages listed above, is beurre, burro, mantequilla, manteiga, Butter, boter, smör, smør, maslo, masło, voi, või, vaj, boútyro. Just five different sets of related words. Look again at the words for butterfly: 15 languages, 15 entirely different words — 16 when you count English. The words for "butterfly" have done about as much fluttering around through history as butterflies have.

So what accounts for this chaos? Witches, women, souls, birds, flowers, fluttering, and mists.

First come the witches. Some Germans at one time had the idea that witches turned themselves into butterflies to steal cream. The word Schmetten means "sour cream" in an Austrian dialect (taken from Czech smetana). From that they apparently made the word Schmetterling for those pretty little witches.

If you think those Germans are funny, guess where we got butterfly from. Yup, it may well have been because we thought they were witches coming to steal the butter. Or it may just have been that people thought butterflies liked butter, or that some of the more common ones in England have pale yellow wings. Or it may originally have involved beating (of wings) rather than butter. What we do know is that it doesn't come from flutter by — the Old English word for butterfly was buttorfleoga, which is too far to flap from flotora be, Old English for flutter by.

Then come the other ladies. Russian for butterfly is babochka, which is a diminutive of baba, "old woman." The story goes that Russians believed that women turned into butterflies when they died. Witches especially. Meanwhile, Spanish children used to sing songs that included verses such as "María pósate, descansa en el suelo," which means "Mary, alight, rest on the ground." From María pósate came the Spanish word for butterfly: mariposa.

Next come the birds and the flowers. The Danish sommerfugl means "summer bird." They have actual birds in Denmark in the summer, too, but there it is. Meanwhile, the Greek petaloúda is related to the word pétalon, which is the Greek origin of petal. So in Greek, butterflies are seen as like flying flowers. Which sure beats witches who steal butter. But in ancient Greek, they used the word psyche, which also meant "soul" — more dead people fluttering around.

And, yes, there's the fluttering: Several of the words in other languages come from imitations of the butterfly's fluttering wings. The ancient Romans thought papilio was a good imitation of the wings flapping. French papillon comes from that, and Italian farfalla and Portuguese borboleta may as well — or borboleta may actually come from Latin for "pretty little thing." Dutch vlinder may be related to a word for "flutter" and may be related to an older imitative word viveltere, which comes from an older Germanic word that may be what developed differently into Swedish fjäril (or fjäril may be related to feathers).

Talk about words fluttering through history. English also has a related word, flinder, but we decided we liked butterfly better — just as the Germans preferred Schmetterling to Feifalter. It's the witches, I tell ya.

And then there are the dark mists of time. The Estonian liblikas and Hungarian lepke are descended from a single Finno-Ugric root, as is an alternative Finnish word, liippo. We're not sure where that root comes from, though it may be borrowed from a Greek word for "scales" (which you'll also see at the start of the genus name Lepidoptera). We are less sure where Hungarian pillangó and Finnish perhonen are from, aside from perhonen being a diminutive of perho, which also means "butterfly." Southern Slavic languages tend to use leptir or a similar word, which may be from the same root as lepke. Some Slavic languages have a word like the Polish motyl, coming from a root that may have to do with sweeping (as in back and forth) or may be related to...um...excrement. Small wonder that the Russians preferred their little old lady babochka.

Pineapples, meanwhile, just sit there. They may be delicious, but they're not magical like butterflies.

Incidentally, in many languages, they use the same or a related word for moth as for butterfly. Some languages call moths "night butterflies." Well, they are closely related. And some languages, such as Italian and Russian, use the same word for bow tie as for butterfly. You can see it, right?

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxes

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxesThe Explainer Your status will determine how much you pay, plus the tax credits and deductions you can claim

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

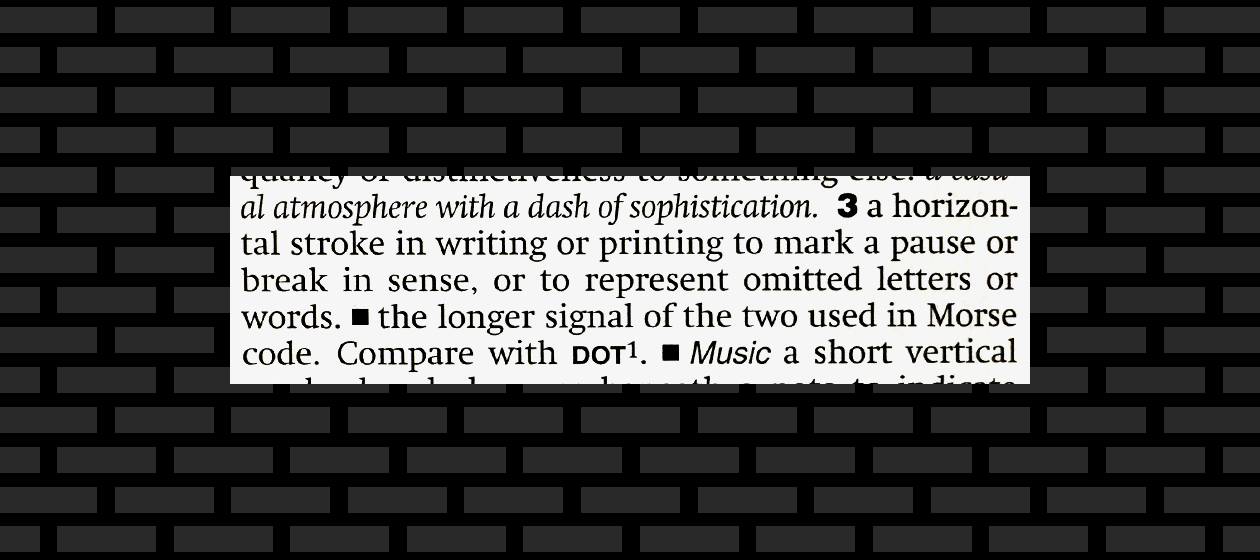

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.