The Netherlands, Holland, and the Dutch: Why some countries have so many different names

Chalk it up to the vagaries of time, and a Germanic tribe or two

A person from Germany walks into a room. So does a person from Allemagne, a person from Deutschland, a person from Saksa, a person from Tyskland, and a person from Niemcy. At least how many people are in the room?

One.

Germany is one of several countries that have completely different names in different languages. In French, Germany is Allemagne; in German, it's Deutschland; in Finnish, it's Saksa; in Danish, it's Tyskland; in Polish, it's Niemcy. Why is this? And what other countries have this quirk? It's all a story of tribes, dynasties, foreign domination, and rivers…

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Germany

A long time ago, when people in part of what is now Germany spoke what we call Old High German, their word for "popular" or "of the people" was diutisc. This has been handed down over history, altered by the general sound patterns of different languages, as the modern German Deutsch, the Danish (and other Scandinavian) Tysk, and the Italian tedesco. Quite a few languages have names for Germany based on this, including most Germanic languages, as well as Korean, Chinese, and Vietnamese.

But not everyone who had contact with the Germans felt inclined to call them what they called themselves. The Gauls, a Celtic people who were in France before the Romans arrived, called their neighbors to the east Germani, which seems to come from a Gaulish word meaning "neighbor" or another meaning "noisy." Think of the Germans as the noisy neighbors of the French. Many languages use a name based on this foreign term.

But the French don't. They call it Allemagne, which comes from Allamanni, which was the name of a Germanic tribe. Other tribes included the Saxons, from which the Finns made Saksa. The Slavic languages, on the other hand, use a word based perhaps on the river Neman, which is near the western boundary of Russia. This is near the border between Poland and Russia, and yet the Polish word for "Germany" is Nemcy — a country on their west named after a river on their east.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Nearly every language in the world uses a word for Germany based on one of those five origins, and you can generally tell which origin the name comes from by the first letter: D/T, G, A, S, or N.

The Netherlands

Meanwhile, there's another place that also gets one of the D/T words: people from the Netherlands are Dutch. You will surely recognize the resemblance to Deutsch. So, why are Hollanders Dutch?

It goes back to the Middle Ages, when the national boundaries were not tidily drawn and Dutch was seen as a kind of Low German ("low" because of the area's low elevation — that's also what the nether in Netherlands means). The label stuck, even as Germans who moved to Pennsylvania came to be called Pennsylvania Dutch, because at the time they got that label, the distinction had still not been firmly made.

But did you notice how I called people from the Netherlands Hollanders? Holland used to be what English speakers normally called the Netherlands. Holland is actually just part of the Netherlands, one that lies along most of the coast and includes the country's three largest cities. So the Dutch people that English traders met were typically from Holland, which is how the name came to be generally used. But people from the rest of the country didn't like that so much, so we don't normally call it Holland anymore.

China

One of the world's great airlines is Cathay Pacific. What is Cathay? Another name for China. And what's China? The English name for Zhongguo. You know, the country the Russians call Kitai.

Here's how that all came to be. About a thousand years ago, a nomadic people called the Khitan started a dynasty in northern China. They were ultimately overthrown and pushed westward, but the name stuck as a term for northern China and spread to a few languages — it's where the Russian Kitai comes from, and the word Cathay too. Marco Polo helped spread it.

Another dynasty, the Qin (formerly spelled Chin), gave us the word China, which shows up in slightly differing form in many languages, from Norwegian Kina to Afrikaans Sjina, as well as the Latin Sino that shows up in terms such as Sino-Tibetan relations.

But in Mandarin Chinese, the country is called Zhongguo (pronounced like "jong gwo"), which translates to "Middle Country" or "Middle Kingdom" — reasonably enough, since from where they're sitting, it's the center of everything.

The Greeks used the name India for the place they had to cross the Indus River to get to — the name Indus comes from Sanskrit Sindhu, passed through Persian and Greek. Most of the world knows the country by a version of India. A few call it by another name that's used in India, especially for the north of the country: Hindustan. But the official name for the country in Hindi is Bharat. That is generally thought to have come from a king, who in turn took his name from the Sanskrit word for "carry, bear" — in fact, it's related to the English word bear (as in carry, not as in animal).

Japan is another country where people in the country call it one thing and almost everyone else calls it another. In Japanese, Japan is Nippon or, more informally, Nihon — which means "where the sun comes from." Why do we call it Japan? Because Marco Polo (him again!) encountered some Chinese traders who called it by their words for "country where the sun comes from," which he wrote down as Cipangu. That got trimmed and changed a bit to make a word that first showed up in English as Giapan. Most of the world now calls the country Japan or something similar.

Korea

We know that Korea is currently two countries, North Korea and South Korea. But did you know that in Korean, they use two historically different names? In North Korea, the country name is Choson; in South Korea, it's Hanguk. Why does everyone else call it Korea or something similar? It comes (does this sound familiar?) from a dynasty that ran the country a millennium ago — the Goryeo.

Finland

Lest you think it's just an East Asian thing for a country to be called by something other than what its own people call it, Finland has the same problem. Well, OK, the name Finland comes from Swedish, and Swedish is one of the two national languages of the country — for the same reason that English is one of the national languages of Ireland: They owned the place for a while and there are still lots of them there. But in Finnish (or Suomea, as they call their language) the name of the country is Suomi. Only a few other languages call it something based on Suomi. The rest go with versions of Finland.

England

We know that it can be a nuisance to look up England in an index, because it could be under United Kingdom (of which England is part) or Great Britain (the island England shares with Scotland and Wales). But add to that the fact that in Celtic languages, England is something else altogether: Sasana (Irish Gaelic), Sasainn (Scots), Bro-Saoz (Breton). Why? Well, England was colonized by the Angles and the Saxons (they took over from the Celtic Britons, some of whom fled to northern France). We take England from the Angles; the Celts took their names from the Saxons. Except for the Welsh — they have their own word, Lloegr, which is something they called that part of the island long before the Angles and Saxons showed up.

Does anyone else use a word based on Saxon? Yes — scroll back up to the top of the story: the Finns do (so do the Estonians)… but they use it for Germany, which is where the Saxons came from in the first place.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

Striking homes with indoor pools

Striking homes with indoor poolsFeature Featuring a Queen Anne mansion near Chicago and mid-century modern masterpiece in Washington

-

Why are federal and local authorities feuding over investigating ICE?

Why are federal and local authorities feuding over investigating ICE?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Minneapolis has become ground zero for a growing battle over jurisdictional authority

-

‘Even those in the United States legally are targets’

‘Even those in the United States legally are targets’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

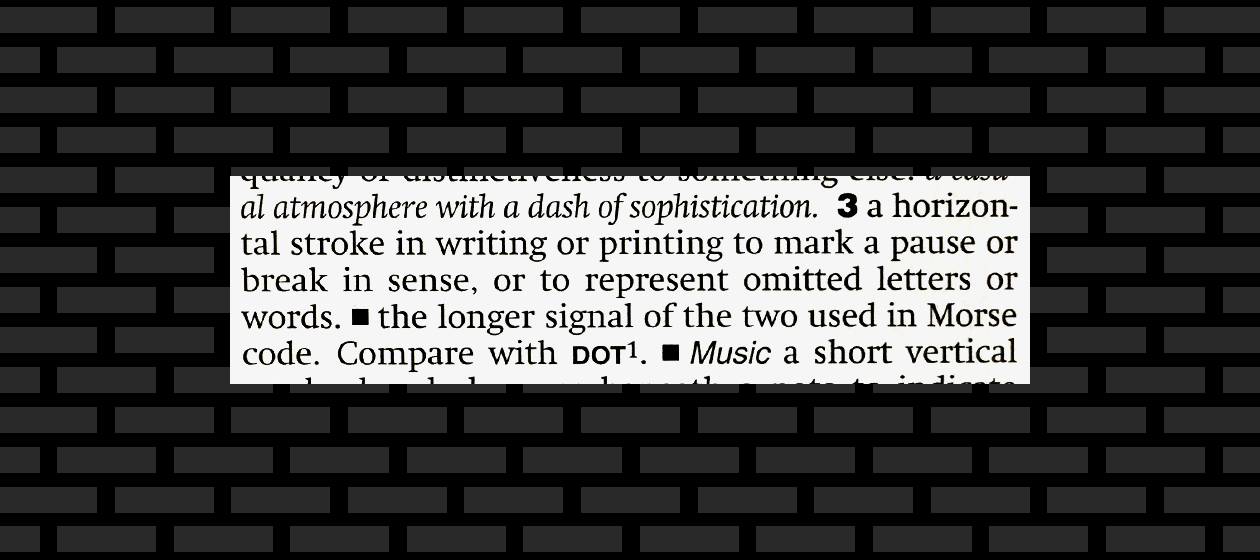

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.