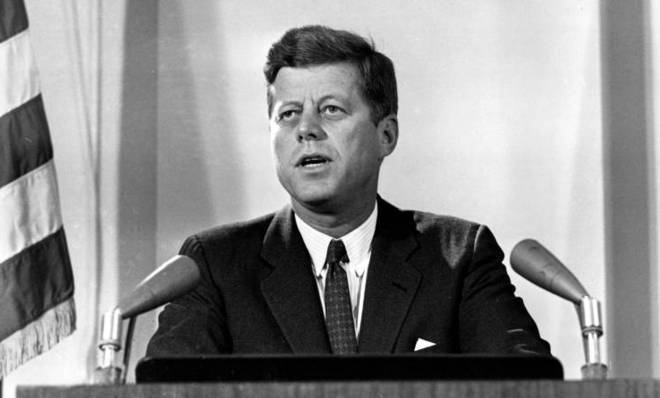

Why the American love affair with John F. Kennedy is winding down

Voters are increasingly critical of Camelot's legacy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Despite the many commemorations for the approaching 50th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, it seems the glitzy and tragic myth of Camelot is losing some of its luster. While Kennedy remains one of the most beloved and revered presidents, the American public is starting to be more critical of the 35th president’s legacy.

A recent New York Times poll showed that 10 percent of Americans rank Kennedy as the best president in U.S. history. That’s nothing to sniff at, but it is at least a 50 percent decrease from the number of Americans who ranked him No. 1 in 2000.

Some would argue this decline is only natural the further we get away from his death. In his book The Kennedy Half-Century, Larry Sabato Jr. writes, “Eventually the public relations fog lifts. There are few or no people left with a personal stake in promoting or condemning ex-presidents. In the case of John Kennedy, we are almost at that moment.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But there is something unique about the insanely high — and until recently, enduring — level of Kennedy’s popularity. While most presidents have enjoyed a bounce in approval since their days in office (Richard Nixon being the one giant postwar exception), a Gallup poll showed that Kennedy’s skyrocketed, to 85 percent in 2010, from 58 percent in his last days. The next closest comparable net gain was of 18 percentage points for Jimmy Carter, which only brought him up to 52 percent approval.

This trend is all the more baffling considering that historians have never held Kennedy in nearly as high esteem as the American public. Alan Brinkley at The Atlantic notes that 13 polls of historians between 1982 and 2011 put him on average as the 12th-best president, and that they generally view him as “a good president, not a great one.”

In fact, the gap between historians and the public suggests that the question may be not why esteem for Kennedy has diminished, but rather how it grew so tremendously in the first place.

One factor is that high school textbooks of the 1960s and 1970s glorified rather than scrutinized Kennedy’s presidency. It wasn’t until later that textbooks rectified those portrayals. As a result, Adam Clymer at the New York Times writes, the image of Kennedy “has evolved from a charismatic young president who inspired youths around the world to a deeply flawed one whose oratory outstripped his accomplishments.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Over time, even events that are considered Kennedy’s greatest accomplishments have been put in perspective. While a 1968 textbook called the Cuban missile crisis an “American triumph [that] was a tribute to Kennedy’s combination of toughness and restraint,” a 2001 textbook said that “his handling of the crisis courted disaster.”

And in addition to textbooks, journalists and pundits are increasingly comfortable scrutinizing the Kennedy legacy, in stark contrast to the media adoration during Kennedy’s presidency that was only enhanced following his assassination.

After his death, journalists scrambled to write glowing accounts of the president. James MacGregor Burns at the New York Times wrote that "Kennedy had the greatness” of Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Roosevelt. According to James Swanson in his End of Days: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy, Life stopped the presses for Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Theodore White to meet with Jackie Kennedy, at which point she fed him the reference to the musical Camelot that would cast her husband's presidency as a brief and beautiful royalty for decades.

Now journalists feel no compunction to foster such a glowing legacy. Just this week, Robert J. Samuelson at the Washington Post curtly dismissed the question of whether Kennedy was a great president, writing, “He was somewhere between middling and mediocre.” Richard Winchester at the American Thinker flat-out skewered him as “a ‘Johnny come lately’ to the cause of civil rights,” and stressed that “no major domestic legislation [is] attached to his name.”

Yet despite these increasingly critical attitudes toward JFK, it’s important to remember that the same Times poll still showed that he is considered the fourth-best president. Perhaps Americans are trying to hold on to the myth of Camelot just a little while longer.

Emily Shire is chief researcher for The Week magazine. She has written about pop culture, religion, and women and gender issues at publications including Slate, The Forward, and Jewcy.

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military