Health & Science

Are boys growing up too fast?; A multivitamin benefit; Tracing the moon’s origins; Could we talk with whales?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Are boys growing up too fast?

Boys in the U.S. now start puberty as much as two years earlier than they did several decades ago, and scientists are puzzling over the reasons and consequences. Doctors tracking the development of some 4,000 young males found that African-American boys tend to begin puberty at 9, while white and Hispanic boys begin at 10. Previously, male puberty was thought to begin between 11 and 12. The findings mirror research that shows girls are developing breasts earlier than in previous generations, a trend possibly caused by obesity and exposure to estrogen-mimicking chemicals. Obesity is less likely to be a factor for earlier male puberty, but changes in diet, exercise, and chemical exposure could play a role. The long-term medical effects of earlier maturity—which might include a heightened risk of testicular cancer— may not be as significant as behavioral ones. “There is already a tremendous gap between sexual maturity and when the brain matures, and it’s probably getting ever greater,” study author Marcia Herman-Giddens of the University of North Carolina tells The Wall Street Journal. That could make younger boys more prone to take the kinds of risks that older teenagers often do.

A multivitamin benefit

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Taking a daily multivitamin can help reduce the risk of cancer. That’s the conclusion of a new study that followed 15,000 men over the age of 50 for more than a decade. Half of the men took a daily multivitamin supplement and ended up 8 percent less likely to develop cancer over the course of the study than those who were given a placebo. The finding is at odds with recent research that concluded that, for women, taking vitamin and mineral supplements offers no real benefit and can cause harm in high doses. The “modest reduction’’ in the risk of cancer is reason enough to take supplements, study author J. Michael Gaziano tells The New York Times, but “it would be a big mistake for people to go out and take a multivitamin instead of quitting smoking” or “eating a good diet and getting exercise.” Though nearly 90 percent of Americans don’t eat the recommended daily servings of fruit and vegetables, about half say they take some kind of vitamin supplement.

Tracing the moon’s origins

Some new thinking may have brought astronomers a step closer to solving the mystery of how our moon formed. Researchers have long believed that the moon was cleaved from a Mars-sized planet that collided with Earth some 4.5 billion years ago. Yet recent tests of lunar rock samples suggest that the moon’s chemical makeup is too similar to Earth’s to have come solely from a foreign body. A team from Harvard University re-examined collision models and found that the early Earth could have been spinning much faster when it was struck than was previously believed—so fast that a day would have lasted less than 3 hours. At that rate, the colliding planets would both have been obliterated, and the resulting debris cloud could have recombined to form Earth and its moon from roughly the same material. Experts are still debating how big Earth and the other planet were when the smashup occurred and are “only part of the way” toward settling on “a more satisfying” explanation for the moon’s origins, Caltech planetary scientist David Stevenson tells the Los Angeles Times. Since the crash demolished most evidence of what both planets were like pre-impact, adds UCLA astronomer David Paige, “it’s a whodunit mystery with very few clues lying around.”

Could we talk with whales?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Human-like sounds made by a captive beluga whale suggest that cetaceans could learn to mimic our voices—and perhaps even converse with us. Researchers at the National Marine Mammal Foundation first noticed in the 1980s that one of their whales was attempting to copy the speech patterns of his handlers and they began recording his human-like vocalizations. Recently, they analyzed those recordings and found that “the beluga did seem to be mimicking human speech, and did so quite successfully”—drastically lowering the frequency of his usual whale calls and matching his utterances to the rhythms of human speech, University of Southern Mississippi marine biologist Stan Kuczaj tells DiscoverMagazine.com. Whales don’t have vocal cords, so to make his human-like sounds, the whale, named Noc, had to change the air pressure in his nasal tract and make other adjustments to valves and sacs connected to his blowhole. Such obvious effort suggests that Noc may have been motivated by a desire for contact with the people around him, says study author Sam Ridgway. Noc died before the research was published, but Ridgway says he left behind an intriguing possibility that other captive belugas could one day learn to communicate with humans at “a conversational level.”

-

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’the week recommends The pasta you know and love. But ever so much better.

-

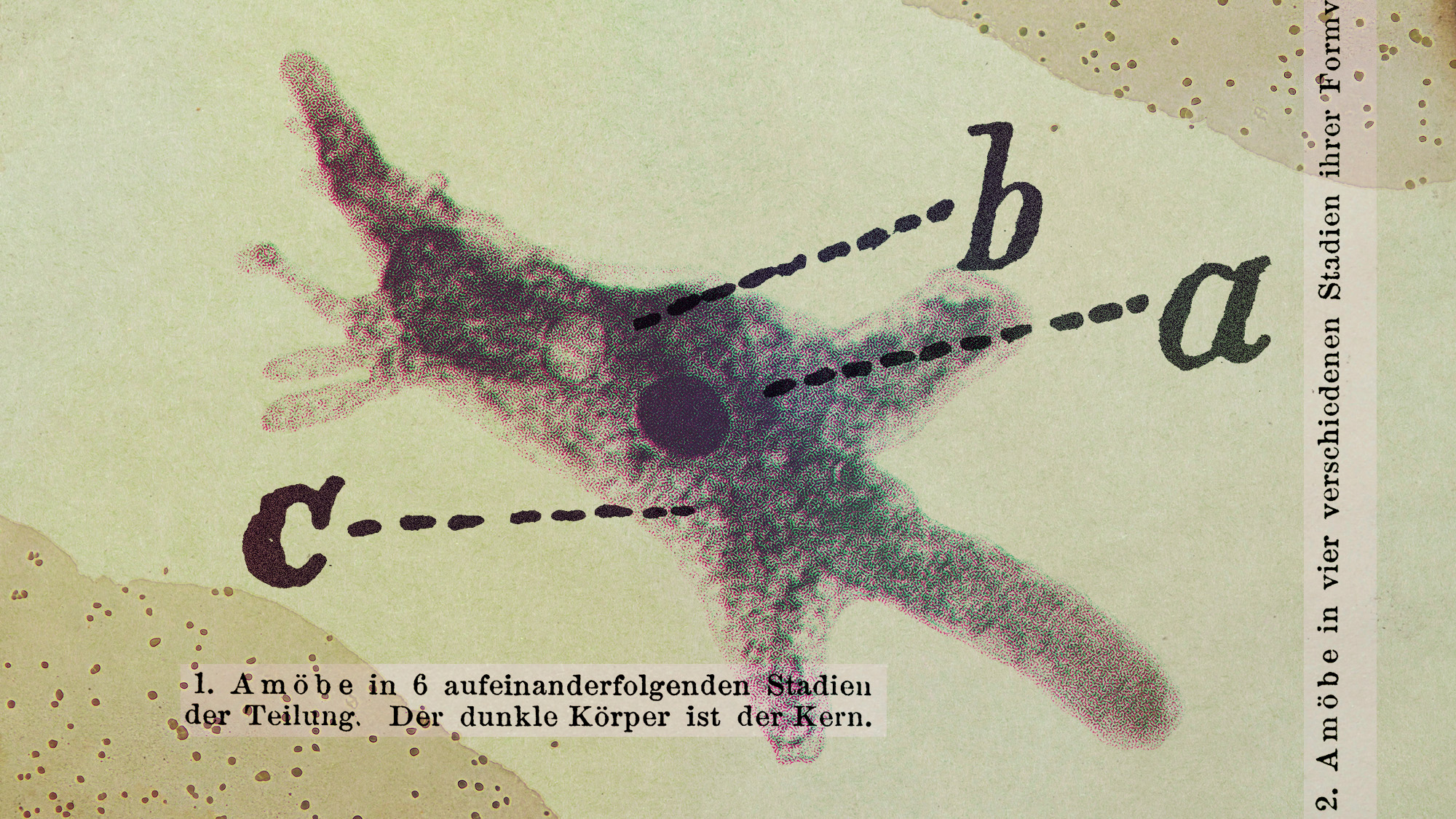

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peace

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peaceUnder the Radar Crowds have turned out on the roads from California to Washington and ‘millions are finding hope in their journey’

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

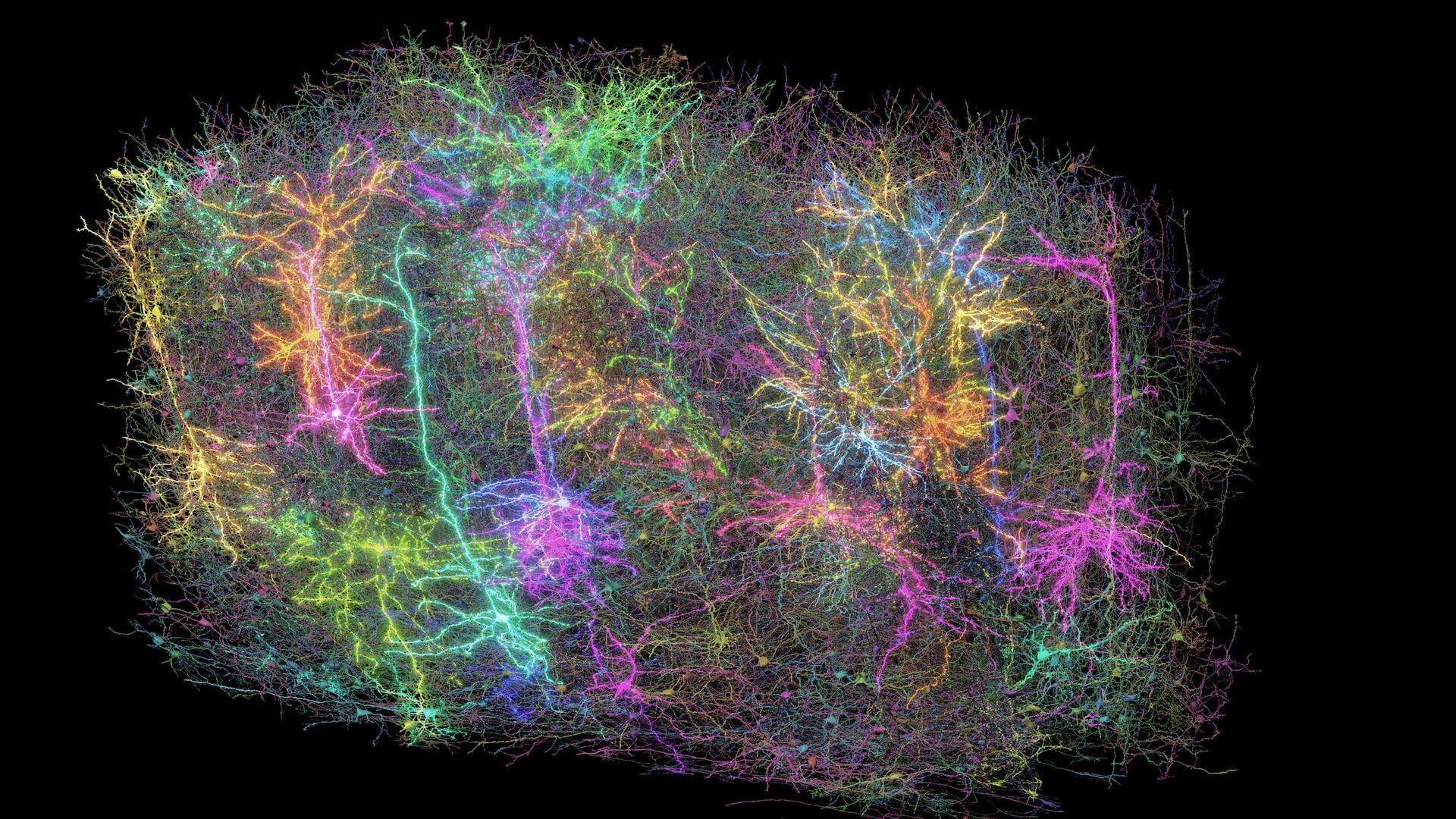

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'