Health & Science

Troubling news for young stoners; The evolution of justice; Calorie restriction and longevity; A boost for circumcision

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Troubling news for young stoners

The “stoner” stereotype isn’t just a myth. Heavy use of marijuana in the teenage years dulls intelligence—and the loss of IQ points may last for life, according to a new study. Researchers tested the IQs of more than 1,000 New Zealand schoolchildren at age 13, before most had tried marijuana, and again at age 38. In between, they regularly surveyed each subject about his or her drug use. They found that those who had started smoking pot regularly before age 18, and continued into adulthood, lost an average of eight IQ points—the difference between scoring in the 50th percentile (average) and the 29th (well below average). Those who waited until after age 18 to make a habit of weed showed no drop in intelligence. “Our hypothesis is that we see this IQ decline in adolescence because the adolescent brain is still developing,” Duke University researcher Madeline Meier tells Time.com. She says marijuana’s active ingredients may interfere with that development, with negative effects on memory and the ability to plan. It’s bad news for American teens, who are smoking pot more than ever before. In a recent survey, 23 percent of high school students said they’d recently smoked pot, and about one in 10 gets high 20 times or more per month.

The evolution of justice

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Chimpanzees, our closest relatives, turn a blind eye to crimes that don’t affect them directly, suggesting that third-party punishment—the foundation of complex societies governed by laws and courts—is a uniquely human development. German researchers trained chimpanzees to play one of three roles while facing one another in cages: One was given access to food within reach of his cage, another could pull a rope to steal the food for himself, and the third could push a button to “punish” the thief by preventing him from getting the treat. None of the chimps pushed the button to punish the thief—even when the victim was a close relative. But when chimps were given the chance to punish the thief for stealing from them, they did. That suggests that humans’ innate sense of justice, which “can allow for cooperation to move beyond simple tit-for-tat,” evolved after our species split from chimps some 5 million years ago, Keith Jensen, a developmental psychologist at Queen Mary University of London, tells DiscoverMagazine.com. Humans’ heightened cooperative capacity was likely key to their evolving bigger brains—and more successful societies—than those of their primate peers.

Calorie restriction and longevity

A 25-year study of rhesus monkeys has cast doubt on the theory that a radically restricted diet leads to a longer life. Since 1987, researchers at the National Institute on Aging have been feeding a group of rhesus monkeys 30 percent fewer calories than the normal intake of a control group. They found that while some of the skinnier monkeys had lower cholesterol levels and a reduced risk of cancer, on average they didn’t live any longer than monkeys fed a normal diet. That result is at odds with previous studies that suggested that severely restricted caloric intake conferred longer life spans in species as diverse as yeast, fruit flies, worms, and mice. Those studies led to speculation that eating much less food on a consistent basis produces fewer aging toxins, and also signals the body to slow metabolic processes. While his new study doesn’t deal directly with human diet, gerontologist Rafael de Cabo tells The Wall Street Journal, it suggests that “calorie restriction is not a Holy Grail for extending the life span of everything that walks on Earth.”

A boost for circumcision

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Circumcising newborn boys leads to healthier infants and men, a new report by the American Academy of Pediatrics has found. A review of 1,000 studies of male circumcision, pediatric bioethicist Douglas Diekema tells Nature News, found that “the medical benefits outweigh the risks of the procedure.” Circumcised babies are 90 percent less likely than uncircumcised ones to develop a urinary tract infection in their first year. Later on in life, they are at lower risk of contracting HIV, herpes, penile cancer, and human papillomavirus, which, when passed to female partners, can cause cervical cancer. Serious complications occur in far fewer than 1 percent of babies who undergo circumcision, and the study found no evidence that it causes sexual problems or lost sensation later on. Nevertheless, circumcision rates are declining; just over 50 percent of parents currently opt for their male babies to have the procedure. Opponents of circumcision believe that it’s a form of mutilation, and say it’s fundamentally unethical to remove a baby boy’s healthy foreskin and cause him pain without his consent. The AAP report fell short of issuing a universal recommendation of circumcision, but said the medical benefits mean parents are ethically justified in deciding to have the procedure performed.

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

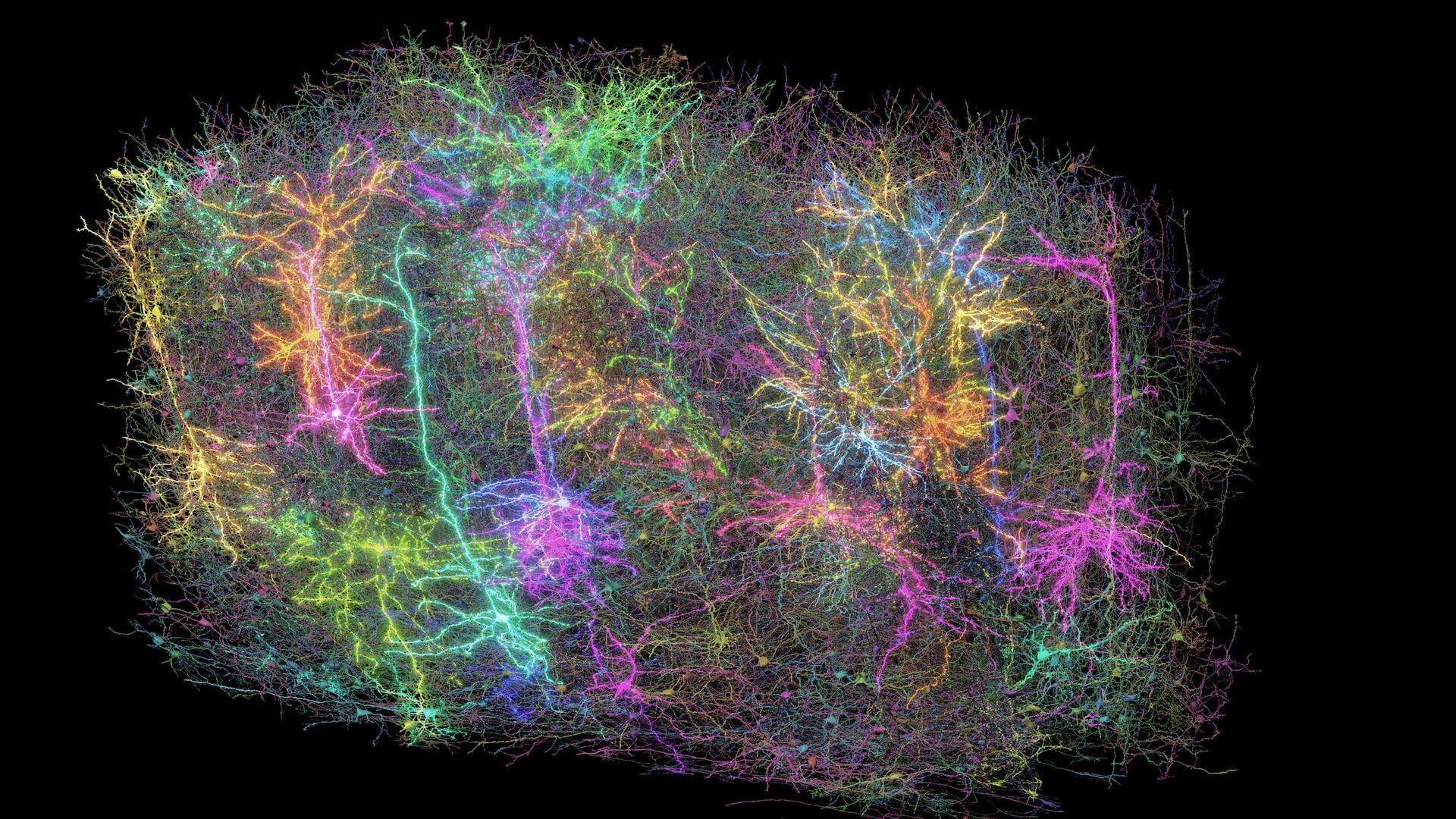

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'